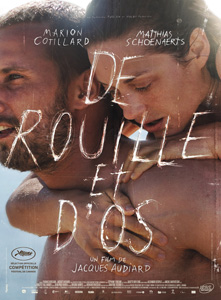

Rust and Bone (De Rouille et d’Os) : Anatomy of a Cannes Shut-Out

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Rust and Bone was released while still in competition at the Cannes film festival. In Paris it garnered mostly superlative reviews and long lines, but the movie came away without a single prize. Was the jury turned off by the film’s marketing machine? The director, Jacques Audiard, comes from French film royalty—his father was the great scriptwriter Michel Audiard—but Audiard fils has also been heavily influenced by American cinema, perhaps another bone of contention. As it happens, Rust and Bone was inspired by an American headline, an accident that happened a few years ago at Sea World, when an orca turned on one of the trainers who perform with the killer whales, took her into its jaws and dragged her to the bottom of the pool, killing her. (As a result, in-the-pool shows with orcas have been banned.) Audiard seems to have wondered what might have happened if the trainer had survived such a terrible attack.

Rust and Bone was released while still in competition at the Cannes film festival. In Paris it garnered mostly superlative reviews and long lines, but the movie came away without a single prize. Was the jury turned off by the film’s marketing machine? The director, Jacques Audiard, comes from French film royalty—his father was the great scriptwriter Michel Audiard—but Audiard fils has also been heavily influenced by American cinema, perhaps another bone of contention. As it happens, Rust and Bone was inspired by an American headline, an accident that happened a few years ago at Sea World, when an orca turned on one of the trainers who perform with the killer whales, took her into its jaws and dragged her to the bottom of the pool, killing her. (As a result, in-the-pool shows with orcas have been banned.) Audiard seems to have wondered what might have happened if the trainer had survived such a terrible attack.

Marion Cotillard brilliantly plays Stéphanie, the beautiful trainer who loses both her legs. Cotillard portrays Stéphanie as a sensual, slightly trashy woman who before her accident is trapped in an unhappy relationship. She first meets Ali (Matthias Schonaerts), a bouncer at a disco-bar, when he escorts her home after she’s roughed up in an altercation. After the accident (at a French version ofSea World) Stéphanie finds her world shattered, with no legs, no job, no lover. She manages to recover to a degree, but joylessly. Cotillard has successfully portrayed larger-than-life characters, like Edith Piaf and a mobster’s moll in Public Enemies. Here she gives what may be her finest performance to date playing woman who’s smaller-than-life (at least “normal” life), movingly expressing her loss and pain, but also her grit.

Stéphanie decides to call the number Ali had given her before the accident. He knows what happened to her—her tragedy has made the media—and they agree to meet. An able-bodied/disabled friendship follows, which turns into something else. It’s reminiscent of Coming Home, Best Years of Our Lives, Children of a Lesser God, life-affirming movies about handicapped persons finding love and happiness despite their disabilities (with the aid of able-bodied stars, of course). Except that the director and Schonaerts also seem to have made a careful study of Martin Scorcese’s Raging Bull. Ali goes from bouncer to being a bare-knuckle (or “mixed martial arts”) boxer, fighting clandestine matches where people pay for blood and lay down bets. Stéphanie, fitted with artificial legs, follows Ali in this repugnant but fascinating milieu.

Stéphanie decides to call the number Ali had given her before the accident. He knows what happened to her—her tragedy has made the media—and they agree to meet. An able-bodied/disabled friendship follows, which turns into something else. It’s reminiscent of Coming Home, Best Years of Our Lives, Children of a Lesser God, life-affirming movies about handicapped persons finding love and happiness despite their disabilities (with the aid of able-bodied stars, of course). Except that the director and Schonaerts also seem to have made a careful study of Martin Scorcese’s Raging Bull. Ali goes from bouncer to being a bare-knuckle (or “mixed martial arts”) boxer, fighting clandestine matches where people pay for blood and lay down bets. Stéphanie, fitted with artificial legs, follows Ali in this repugnant but fascinating milieu.

Schonaerts is physically impressive, intense, and plays his Raging Bull role to the hilt. But that role is utterly one-dimensional. It’s riveting to watch for much of the movie, and Schonaerts always holds our attention, but his performance gets tiresome (or maybe the spectator gets punch-drunk). Perhaps this draining element is what turned off some at Cannes.

Schonaerts is physically impressive, intense, and plays his Raging Bull role to the hilt. But that role is utterly one-dimensional. It’s riveting to watch for much of the movie, and Schonaerts always holds our attention, but his performance gets tiresome (or maybe the spectator gets punch-drunk). Perhaps this draining element is what turned off some at Cannes.

Director Audiard also seems to have unwittingly rope-a-doped himself. He films wonderfully, inspired by naturalistic directors like the Dardennes brothers and expressionistic directors like Scorcese. He obviously knows how to direct actors superbly. But though he delivers exciting performances from two very talented actors, he doesn’t really know what to do with them. Ali gets all bloody, and then what? Even Marion Cotillard’s Stéphanie has nowhere to go. Audiard seems to use the character’s infirmity as his own crutch. The movie has been compared to Tod Browning’s Freaks, but there’s a difference: the actors in that movie really were freaks. Watching Cotillard we’re impressed by the special effects (graphically showing her stumps) but we’re mostly wondering “How do they do that?” rather than following a human being’s narrative arc.

The bottom line is that Jacques Audiard has many movie-making skills, but not his father’s story-telling genius. We feel cheated when we recognize one subplot—Ali getting involved in a cockamamie store-surveillance scheme—as just a contrivance to manipulate the character’s relations with his sister (who’s taking care of his child). At the three-quarters mark Ali abruptly pulls a geographical, fleeing his relationship with Stéphanie. That might have to do with his character, but we suspect it’s really Audiard fleeing his dead-end scenario. His ultimate way out is hoary melodrama, and moving from Raging Bull to Rocky. That seems to have worked with French audiences and critics, but maybe the Cannes jury members had something there.

The bottom line is that Jacques Audiard has many movie-making skills, but not his father’s story-telling genius. We feel cheated when we recognize one subplot—Ali getting involved in a cockamamie store-surveillance scheme—as just a contrivance to manipulate the character’s relations with his sister (who’s taking care of his child). At the three-quarters mark Ali abruptly pulls a geographical, fleeing his relationship with Stéphanie. That might have to do with his character, but we suspect it’s really Audiard fleeing his dead-end scenario. His ultimate way out is hoary melodrama, and moving from Raging Bull to Rocky. That seems to have worked with French audiences and critics, but maybe the Cannes jury members had something there.

Production: Why Not Productions

Distribution: UGC (international: Celluloid Dreams)

All images copyright Roger Arpajou Why Not Productions

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

We update our daily selections, including the newest available with an Amazon.com pre-release discount of 30% or more. Find them by starting here at the back of the Travel section, then work backwards page by page in sections that interest you.

Current favorites, including bestselling Roger&Gallet unisex fragrance Extra Vieielle Jean-Marie Farina….please click on an image for details.

Click on this banner to link to Amazon.com & your purchases support our site….merci!

More in Cannes, Cannes film festival, film review, movie, Paris movie, review