Eugéne Atget – The Accidental Artist

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The visual history of Paris is inseparable from the name Eugène Atget, which is a very handy thing to know if you’re in Paris between now and 29 July. Should you wish to see an exhibition that IS Paris, rather than simply in Paris, I highly recommend you set a course for the Musée Carnavalet in the heart of the Marais. The photographs (many of them exhibited for the first time) invite us into Atget’s Paris, where he meticulously documented the streets, shops, windows, pedlars, parks and prostitutes of the city in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The visual history of Paris is inseparable from the name Eugène Atget, which is a very handy thing to know if you’re in Paris between now and 29 July. Should you wish to see an exhibition that IS Paris, rather than simply in Paris, I highly recommend you set a course for the Musée Carnavalet in the heart of the Marais. The photographs (many of them exhibited for the first time) invite us into Atget’s Paris, where he meticulously documented the streets, shops, windows, pedlars, parks and prostitutes of the city in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The Man

Little is known about Atget’s life; relative obscurity during his lifetime means the details of his life must be pieced together from fragments of knowledge passed down anecdotally or hinted at in the few written records remaining. What we do know is that Atget was born in 1857 the son of a coach-builder but was an orphan by the age of five. Raised by his grandparents he later worked on ships and sailed as far as Africa and South America before returning to France.

It wasn’t until 1878 that Atget settled in Paris where he was rejected by the Music and Dramatic Art Conservatoire. After conducting his military service he was later accepted to the same Conservatoire and there met the man who would become his closest friend, André Calmettes.

In 1886 Atget met the companion of his life, the actress Valentine Compagnon. The couple remained childless. It was in 1890 that Atget set himself up professionally as a commercial photographer, painting on the door of his studio a sign reading “Documents for Artists.”

In 1897 Atget began the systematic visual documentation of the neighbourhoods of Paris, moving in 1899 to a 5th floor apartment in Montparnasse where the couple would stay for the rest of their lives. Working steadily and successfully but without artistic recognition it was not until 1925 that Man Ray’s assistant, the photographer Berenice Abbott, discovered Atget’s photographs and recognised them for their own artistic merit. Man Ray subsequently published four of Atget’s photographs in an issue of La Révolution Surréaliste –a publication to which Atget agreed on the strict understanding that his name would not accompany the images. Abbot and Man Ray’s championing of Atget’s work brought him to the attention of artists in their circle – Julien Levy, an American filmmaker, bought as many of Atget’s negatives as the photographer would permit.

In 1897 Atget began the systematic visual documentation of the neighbourhoods of Paris, moving in 1899 to a 5th floor apartment in Montparnasse where the couple would stay for the rest of their lives. Working steadily and successfully but without artistic recognition it was not until 1925 that Man Ray’s assistant, the photographer Berenice Abbott, discovered Atget’s photographs and recognised them for their own artistic merit. Man Ray subsequently published four of Atget’s photographs in an issue of La Révolution Surréaliste –a publication to which Atget agreed on the strict understanding that his name would not accompany the images. Abbot and Man Ray’s championing of Atget’s work brought him to the attention of artists in their circle – Julien Levy, an American filmmaker, bought as many of Atget’s negatives as the photographer would permit.

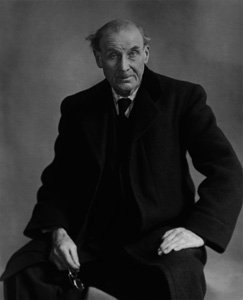

Atget was 70 when Berenice Abbott persuaded him to sit for a portrait at her studio in 1927. Valentine had passed away the previous year. Soon after Abbott visited Atget to share the results of the sitting, only to be told the photographer had died. Anxious that his work be recognised and remembered Abbott approached André Calmettes, Atget’s old friend and executor of the will. Calmettes divided the negatives between Abbott and the Commission des monuments historiques, ensuring the survival of Atget’s life’s work.

The Legacy

Atget’s work was never exhibited during his lifetime: within a year of his death his photographs were included in two exhibitions. Articles on Atget and his life’s work soon followed, were swiftly followed by books on the subject. Soon Atget was hailed as the founding father of modern photography. Atget’s influence can be clearly seen in Berenice Abbott’s photography, while many other prominent 20th century photographers have openly acknowledged the debt they owe to this unassuming artists, who himself never accepted the title.

Atget’s work was never exhibited during his lifetime: within a year of his death his photographs were included in two exhibitions. Articles on Atget and his life’s work soon followed, were swiftly followed by books on the subject. Soon Atget was hailed as the founding father of modern photography. Atget’s influence can be clearly seen in Berenice Abbott’s photography, while many other prominent 20th century photographers have openly acknowledged the debt they owe to this unassuming artists, who himself never accepted the title.

What is fascinating about Atget is the artistic paradox he has come to represent: Atget is celebrated as ‘the father of modern photography’ and yet he himself was adamant that the photographs he created were not artworks but documents. Factual records, nothing more. As a commercial photographer in Montparnasse Atget’s photographs were sold to museums as historical documentation of a Paris that was disappearing; what Atget called ‘Old Paris.’ He made no claim for their artistic importance or sensibility, made no claim to be an artist, and yet since his death Atget has become just that – an accidental artist perhaps, but an artist nonetheless.

The Exhibition

Having first been introduced to Atget as an art history student, I was enthralled by these haunting, poignant records of Old Paris. Beautifully framed and atmospherically lit the photographs are among some of the most fascinating you will ever see of Paris; one cannot help but long to step into the frame and wander Atget’s streets.

It is an uncanny, surreal experience to study so closely the expressions of those Atget chose to record in his photographs. In viewing the images we ourselves become Atget’s lens; a witness to the instant at which the image was captured. We become Atget, crouching under the cloak of the apparatus, focusing the image and waiting the long moments for the correct exposure.

Once the moment of capture had passed those same people – which you are at that same moment studying in a gallery in the same city a century later – wandered away, each subject returning instantly to his or her daily life without much thought for the finished result, their entrance into history, and art history at that. Those same clothes, those lives captured in that one instant have long since passed away and yet – here we are, over a hundred years later, scrutinising them through time, held forever in that one moment of capture. The poignancy of these records is inescapable; Atget was not only recording Paris’ buildings and streets but her people.

Once the moment of capture had passed those same people – which you are at that same moment studying in a gallery in the same city a century later – wandered away, each subject returning instantly to his or her daily life without much thought for the finished result, their entrance into history, and art history at that. Those same clothes, those lives captured in that one instant have long since passed away and yet – here we are, over a hundred years later, scrutinising them through time, held forever in that one moment of capture. The poignancy of these records is inescapable; Atget was not only recording Paris’ buildings and streets but her people.

Atget was concerned primarily with the disappearance of Old Paris and his life’s work centred on the importance of recording what he believed would soon cease to exist. It is this that translates for the modern audience into poignancy and gives us a sense of the uncanny – he was right of course, but it is often the people who have vanished, the way of life. Many of the buildings, bridges, sculptures and parks remain.

The exhibition is given depth and description through the accompanying text (in French and English) explaining Atget’s methods and documenting his career. I cannot recommend this exhibition strongly enough to anyone who would like to visit Old Paris – dreamlike, captivating, you’ll see Paris as you’ve never seen her before.

1. Marchand ambulant, place Saint Médard, 5e arrondissement, septembre 1899 Eugène Atget Tirage sur papier albuminé Paris, musée Carnavalet © Eugène Atget / Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet

2. Eugène Atget, 1927 Berenice Abbott © Berenice Abbott/Commerce Graphics, New York

3. La Conciergerie et la Seine, brouillard en hiver, 1er arrondissement, 1923 Eugène Atget Tirage sur papier albuminé mat Paris, musée Carnavalet © Eugène Atget / Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet

4. Rue Asseline, 1924-1925 Eugène Atget Aristotype à la gélatine Collection Man Ray 1926 © Eugène Atget/Album de Man Ray, George Eastman House

More in Art, France artists, French artists, musee carnavalet, Museum, Paris art exhibits, Paris art museums, Paris artists, Paris museums