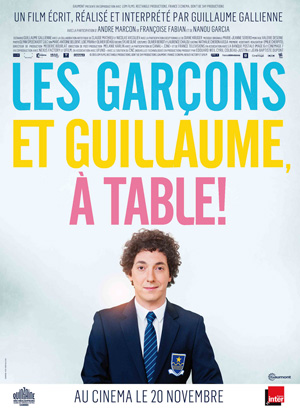

Les Garçons et Guillaume à Table!

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Les Garçons et Guillaume à Table (literally The Boys and Guillaume, At the Table) did very healthy box office in France and won the César for Best Picture (over stiff competition like La Vie d’Adèle and Jimmie P.) But despite starring the talented Guillaume Gallienne (“of the Comédie Française”), who also wrote and directed, dealing with the current go-to subject of sexual orientation, and having many funny moments, it’s unlikely to transcend the local market as The Artist did a couple years ago.

Les Garçons et Guillaume à Table (literally The Boys and Guillaume, At the Table) did very healthy box office in France and won the César for Best Picture (over stiff competition like La Vie d’Adèle and Jimmie P.) But despite starring the talented Guillaume Gallienne (“of the Comédie Française”), who also wrote and directed, dealing with the current go-to subject of sexual orientation, and having many funny moments, it’s unlikely to transcend the local market as The Artist did a couple years ago.

For one thing, there isn’t much of a dramatic premise. The story hinges on the eponymous Guillaume’s having written a stand-up routine based on his life (specifically life with his mother). The movie segues from Guillaume on stage before an audience to scenes in his life. Other films have used similar gimmicks to frame a story (Cabaret being one example; Iron Lady another, in a different way). Because the gimmick is so theatrical the film feels like one long stand-up piece. (The film is in fact an adaptation of Gallienne’s semi-autobiographical one-man show.) French audiences laugh at the behavioural and verbal riffs as if they’re spending an evening at a café-théâtre. But the routines, well done as they are, don’t always translate very well.

Gallienne (who was perhaps the best thing in the Yves Saint-Laurent biopic) does a fantastic job inhabiting not one but two roles. Firstly, he plays Guillaume, scion of a wealthy family, whom everyone, especially in his family, assumes is gay. He does an old-fashioned campy turn as a fun-loving, warm-hearted guy whose gender bender confusion results in a Job-like series of harrowing but comic afflictions. It’s a hilarious performance, with a wry edge, straight out of La Cage Aux Folles.

Gallienne also plays Maman, Guillaume’s mother. Maman is one of those classic monster moms who run amok in gay (and ethnic) fiction. Gallienne’s performance is more mimicry than acting. Even if his talent compares with the great trans-acting ranks of Jack Lemmon, Dustin Hoffmann, and Robin Williams, it doesn’t go beyond mimicry. There are wonderful female comic actors, such as Josiane Balasko, who could have brought genuine depth to the role. But Guillaume is a virtuosity showcase, not a vehicle for the human comedy.

Gallienne also plays Maman, Guillaume’s mother. Maman is one of those classic monster moms who run amok in gay (and ethnic) fiction. Gallienne’s performance is more mimicry than acting. Even if his talent compares with the great trans-acting ranks of Jack Lemmon, Dustin Hoffmann, and Robin Williams, it doesn’t go beyond mimicry. There are wonderful female comic actors, such as Josiane Balasko, who could have brought genuine depth to the role. But Guillaume is a virtuosity showcase, not a vehicle for the human comedy.

Every other role in the film is a caricature or stereotype, sometimes played with farcical verve, but mostly staying on the level of TV sitcom or variety show. The comic stick figures pile up as we follow Guillaume’s progress. He is first sent to a French boarding school he likens to a Turkish prison, then to a more congenial British school, where he develops an ambiguously-requited crush on a boy names Jeremy (Charlie Anson). This is followed by an army medical examination center when he is called up for conscription, and then a spa staffed by sadistic Germans.

Guillaume has technique and production values, but no real style. The vignettes and set-pieces are carefully composed and coordinated, always within the stand-up armature. Again, it’s more or less filmed theatre, or cinematized TV. As sympathetic as Guillaume is, and as talented as Gallienne is playing his alter ego, the relentless, unmediated focus on him is too much. Guillaume is the film’s be-all, end-all, and finally (for us) sick-of-it-all.

And what is the point of this life-story as stand-up routine? The Cage Aux Folles-style camp is funny in its retro way. When the allegedly gay protagonist is shown to be more complex than we’d thought it might be seen as subverting old stereotypes. Or is it just declawing them? Renato and Albin in Cage were what they were, stereotypes and all. Guillaume is what he is, as well, and more power to him. It’s just that what he is turns out to be as conventional as any of our own conformist selves. We want more than that in a subversive comedy. Ultimately Guillaume is just a foible-tolerating feel-good film. As for awards competitions and ceremonies highlighting innovative films, in France the standard is still the Cannes film festival, which is fortunately starting in only a handful of weeks.

And what is the point of this life-story as stand-up routine? The Cage Aux Folles-style camp is funny in its retro way. When the allegedly gay protagonist is shown to be more complex than we’d thought it might be seen as subverting old stereotypes. Or is it just declawing them? Renato and Albin in Cage were what they were, stereotypes and all. Guillaume is what he is, as well, and more power to him. It’s just that what he is turns out to be as conventional as any of our own conformist selves. We want more than that in a subversive comedy. Ultimately Guillaume is just a foible-tolerating feel-good film. As for awards competitions and ceremonies highlighting innovative films, in France the standard is still the Cannes film festival, which is fortunately starting in only a handful of weeks.

Production: Don’t Be Shy, France 3, Gaumont

Distribution: Gaumont

photos © Thierry Valletoux Gaumont – Rectangle Productions – LGM Cinéma

More in film review, french cinema, Paris film