Icons of French Cinema at galerie JOSEPH minimes in the Marais

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

We’re all familiar with promotional photos and posters for movies – the ones showing romantic lovers gazing into each other’s eyes, or creepy people gazing menacingly into the camera, or small figures on a promontory above an ominous sea. Most of us assume they are frames from the film, but perhaps surprisingly, usually they are not. Rather, they are posed photographs taken by photographers tasked with capturing the spirit of the film to entice viewers.

The names of the photographers who took those photos are almost never known, and most of us never think to ask who took them. Thus, they remain anonymous and unrecognized, even though their work is sometimes indispensable to a film’s success.

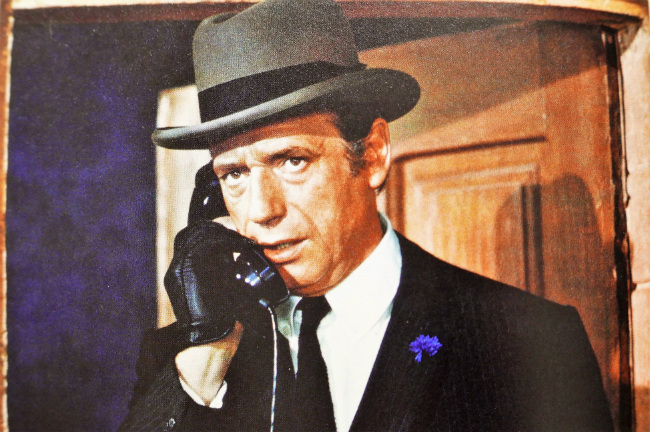

Yves Montand 1968 – le Diable par la Queue by Philippe de Broca © Georges Pierre

The new exhibition at galerie | JOSEPH |minimes in the Marais, Icônes de la Nouvelle Vague aux Années 70 (Icons of the New Wave in the 70s), is the first exhibition to explore the intersection between film and photography – what the exhibition catalog calls “the vital rapport… between the cinematography itself and the still images that document the film’s production and serve its promotion.” It is an effort to show that the photographs intended to promote a film have a quality, identity, and value in their own right, to give credit where credit is due, and to bring to light the names of the photographers whose work any movie aficionado would recognize, but usually without knowing the photographer’s name.

The more than 100 photographs in the exhibition focus on the work of two of the greatest French “stills” or “on-set” photographers – Raymond Cauchetier and Georges Pierre – who both helped create and document the Nouvelle Vague – the New Wave – of French cinema in the mid-1950s.

François Truffaut and the camera team of Denys Clerval 1968 – Baises Volés by François Truffaut © Raymond Cauchetier

A little context.

By the mid-1950s, cinema had been around for nearly 50 years, the first movie theatre having been opened in 1905 in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and the medium was dominated by Hollywood studios. It was probably inevitable that the system would be challenged – the status quo always eventually is – and it was, most notably in France by Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, who rejected the artifice and narrative conventions of mainstream cinema.

Godard and Truffaut first discussed their ideas in Les Cahiers du Cinéma, the oldest French-language film magazine in publication. Eventually, however, they started making movies that put their words into action. Truffaut’s 1959 movie, Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows), and Godard’s À Bout de Souffle (Breathless) portrayed a gritty realism, in contrast to the fantasy and escapism then dominating movies. Other such directors included Claude Chabrol, Jacques Demy, and Alain Resnais. These New Wave directors smashed the existing paradigm of movie making by filming in real locations instead of on movie sets, and by using natural light and more improvisational cinematography. They even broke the narrative rules with deliberate discontinuity; as Godard said, “a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

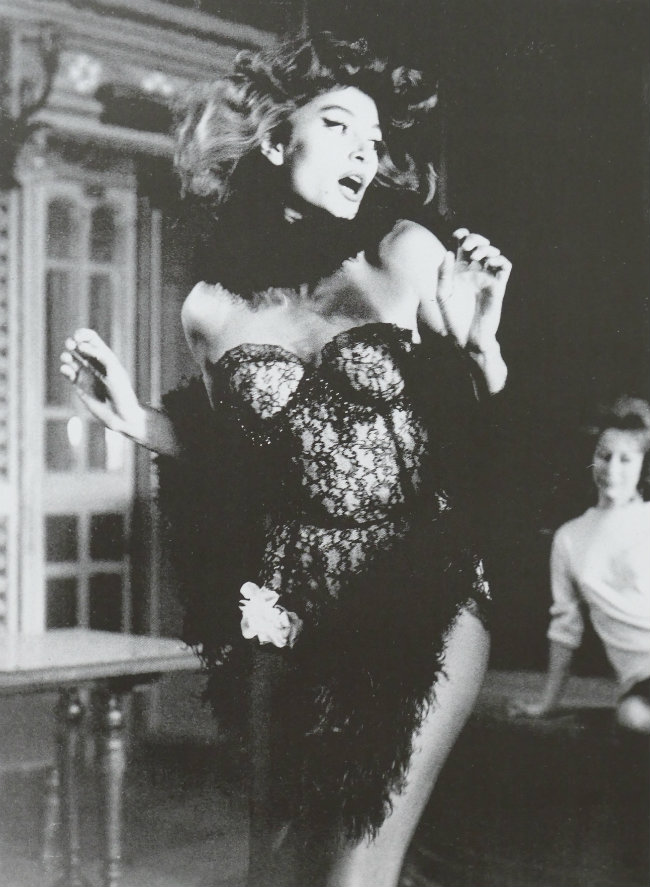

Catherine Deneuve 1967 – Manon 70 by Jean Aurel © Georges Pierre

An important part of the context in which New Wave cinema arose was the fact that World War II had ended just a few years before, and existentialism had flowered in France under Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone De Beauvoir, and Albert Camus. At the same time, the invention of smaller format cameras and faster lenses and film made it easier to free cinema from the studio.

It was within this context that Raymond Cauchetier and Georges Pierre, the Icônes whose work is explored in the exhibition, working with Truffaut, Godard, and other directors, produced some of the photographs which are themselves considered icons of French cinema, and which in the process also made icons of the actors they photographed, such as Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Seberg, Jeanne Moreau, Catherine Deneuve, Yves Montand, Anna Karina, and Romy Schneider.

Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg 1959 – À Bout de Souffle by Jean-Luc Godard © Raymond Cauchetier

Raymond Cauchetier was born in Paris in 1920. He was a member of the resistance during World War II and began photographing while in the army. Awarded the Legion of Honor by de Gaulle for his service in Indochina, he left the army in 1954 and published a well-received book of war photographs. In Paris he tried to get a job as a reporter, but with no success, so he returned to Indochina, where he was offered his first job as a cinema photographer for a film by French director Marcel Camus, with the responsibility of taking a photo at the end of a shot.

But Cauchetier decided to expand the role of the cinema photographer to one of reporter. Accordingly, he took photos of everything – the equipment, the shooting conditions, the directors, and the actors – thus recording in real time the revolution in cinematography that he simultaneously helped advance and record and which became known as the New Wave.

Anouk Aimée 1960 – Lola by Jacques Demy © Raymond Cauchetier

Indeed, he took some of the most famous photographs of cinema of the 1960s: Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg on the Champs-Élysées in Godard’s À Bout de Souffle (1961); Jeanne Moreau, Henri Serre, and Oscar Werner running on a bridge in Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1961); and of Anouk Aimée in Jacques Demy’s Lola (1960). Age 98, Cauchetier lives in Paris, a living icon.

Georges Pierre was born in Nyons, France, in 1921, and before settling on a life as a photographer, he was an engineer, served on the staff of a laboratory that did research on the technical aspects of radio, co-founded an organization of film technicians, and for three years was the director of image research of the Office of French Broadcasting-Television (ORTF). He also studied drama with the intention of becoming a comedian. He had small roles in several films and also toured Africa, which resulted in the publication of his first photographs and a job shooting for Elle magazine. He then joined the Gamma news agency and then Sygma. Later he was editor of Photo magazine.

Delphine Seyrig 1960– L’Année Dernière à Marienbad by Alain Resnais © Georges Pierre

In 1961, New Wave director Alain Resnais asked him to work on L’Année Dernière à Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad). Between 1961 and 1992 he worked with major French directors that, besides Resnais, included Godard, Louis Malle, and Claude Chabrol. Along the way, he invented a soundproofing device called “the blimp,” which allowed still photographers to shoot while a movie was being filmed.

Pierre was inspired by the many talented directors, actors, and other people in the world of cinema, but particularly by Romy Schneider, whom he met in 1972 while working on Claude Sautet’s César et Rosalie.

Romy Schneider 1972 – César et Rosalie by Claude Sautet © Georges Pierre

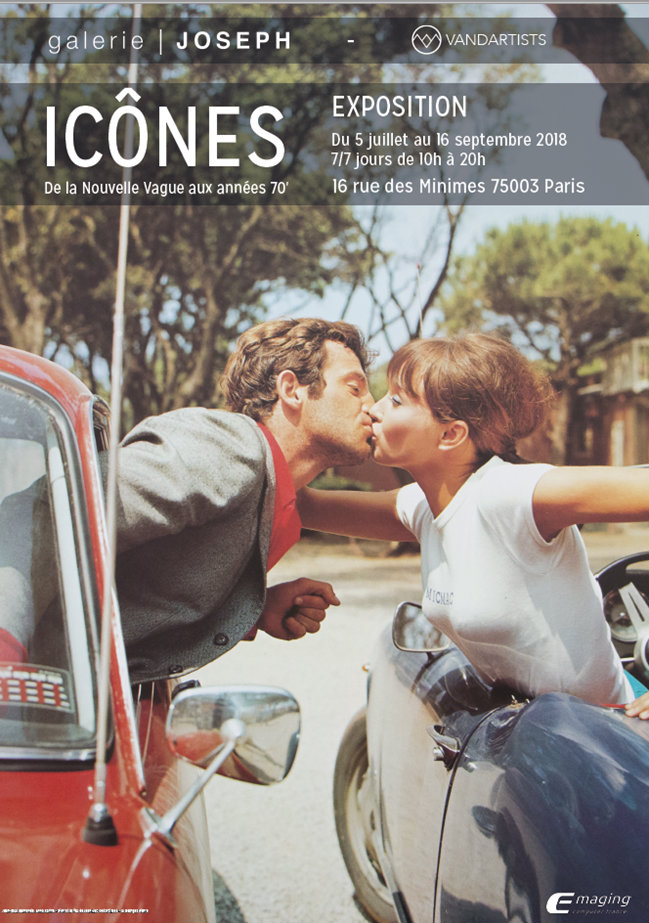

Photographs from among the 100 films Pierre worked on that are considered icons of cinema photography are of the blue-faced Jean-Paul Belmondo in Godard’s Pierrot le Fou (Pierrot the Fool); Delphine Seyrig in Resnais’s L’Année Dernière à Marienbad; and the kiss between Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina while in separate convertibles in Pierrot le Fou, a photo taken in 1965 and chosen as the official poster of the 71st Cannes Film Festival, held earlier this year.

Courtesy of galerie | JOSEPH |minimes

Pierre was co-founder of the Association of Film Photographers, an organization dedicated to the protection of the rights of film photographers. He died in 2003 in Paris.

Icons of the New Wave in the 70s is as pleasurable to view as it is informative about an important period in the evolution of cinema. The clean lines of the gallery itself, clearly designed with an architect’s eye, make it a calming, light-filled, and harmonious space. Anyone who has even a passing interest in film and photography will find the photographs fascinating in their composition and all that they convey. And it’s about time the cinema photographers have been brought out of the shadows and given the attention they so richly deserve.

galerie | JOSEPH |minimes

Icônes de la Nouvelle Vague aux Années 70 through September 16

16, rue des Minimes, Paris 3rd. Tel: + 33 (0)1 42 71 20 22; +33 (0)1 42 71 20 22. Website: http://galeriejoseph.com/en/blog/2018/06/20/icones/.

Métro: Line 1, Saint-Paul; Line 8, Chemin Vert; Line 5, Bréguet-Sabin. Bus: 20, 29, 65, and 96.

Open: Daily 10am to 8pm; no café but plenty of places nearby. Entrance fee: 9 euro. Catalogue: 10 euro

Jean-Paul Belmondo 1965 – Pierrot le Fou by Jean-Luc Godard © Georges Pierre

Lead photo credit : François Truffaut 1961 – Jules et Jim by François Truffaut © Raymond Cauchetier

REPLY