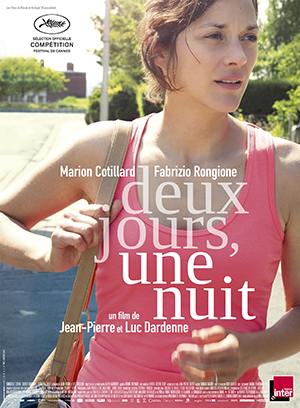

Deux Jours, Une Nuit (Two Days, One Night): Sixteen Angry Workers

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Now that Ken Loach is getting long in the tooth, the Belgian brothers Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne have become the reigning co-monarchs (or co-commissars) of the European social film. 2011’s The Kid with a Bike was a brilliant mix of harsh social observation and sentiment. Their disappointing Deux Jours, Une Nuit (literally Two Days, One Night) may work as an effective tear-jerker (it convinced a jury in Cannes, where it won a special prize) but it’s too schematic to be a very good film.

Now that Ken Loach is getting long in the tooth, the Belgian brothers Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne have become the reigning co-monarchs (or co-commissars) of the European social film. 2011’s The Kid with a Bike was a brilliant mix of harsh social observation and sentiment. Their disappointing Deux Jours, Une Nuit (literally Two Days, One Night) may work as an effective tear-jerker (it convinced a jury in Cannes, where it won a special prize) but it’s too schematic to be a very good film.

Marion Cotillard plays Sandra, a worker at a Belgian firm that makes solar panels. The company, facing competition from Chinese manufacturers, must cut costs. This comes down to the workers sacrificing a bonus, or else one of their number being sacked. In the manner of the Nazi in Sophie’s Choice, the nefarious bosses leave the choice to the workers. They vote for the lay-off, but improprieties lead to a second vote. The backstory that comes out is that Sandra suffered from depression, which may or may not have affected her efficiency at work. Her husband Manu, underlining the importance of her salary to the family, tells her to contact each and every co-worker to persuade him or her to vote against dismissal.

On one level, Deux Jours, Une Nuit is a race-against-the-clock story, social drama division (Gravity was a sci-fi version). There’s no ticking clock as in High Noon (the Western version), but each encounter with a co-worker represents another bit of sand falling through the hourglass. The story is also like Twelve Angry Men, in which Henry Fonda worked on fellow jurors to acquit a youth accused of murder. Twelve Angry Men was intensely focused as it developed its character relationships. The Dardennes’ Sixteen Angry Workers is more episodic, with Sandra going from one person to another, interacting in a sympathetic or angry way, then moving on. This is relieved by an inset drama about a female co-worker, but it’s too little, too late.

As usual, the Dardenne brothers are masterly in depicting an industrial, working-class area. They don’t poeticize at all, but there’s something about the clarity and richness of the photography that brings to mind Old Master painting. The filming of secondary characters also evokes figures in Flemish paintings.

As usual, the Dardenne brothers are masterly in depicting an industrial, working-class area. They don’t poeticize at all, but there’s something about the clarity and richness of the photography that brings to mind Old Master painting. The filming of secondary characters also evokes figures in Flemish paintings.

Marion Cotillard is ravishing to look at, even when she’s supposed to be miserable. She also has a powerful presence, and a seamless, natural acting technique. She chews up the screen, and that’s the problem. She brings to mind Holden Caulfield’s complaint about Laurence Olivier in The Catcher in the Rye—that he was too commanding playing a screwed-up kid (Hamlet). Fabrizio Rongione as the husband gives a low-key, but more human, performance.

Sandra is shown with an ever-present container of anti-depressants, from which she frequently pops a tablet or two. This reminds us of her past, and her present-day vulnerability. The container also serves as a Chekhovian pistol in a fairly predictable way. The unfortunate thing is that it hazes up Sandra’s character. We’re never sure if she’s acting authentically, out of depression, or because of the pills.

What limits the film even more is the ideological lid on the Dardenne brothers’ conception of how the world works. A well-known economic fallacy is that there’s a fixed pool of jobs. This reasoning was used to keep women and minorities out of the work force, and still figures in debates about immigration. It results in the idea that a job is for life, and that someone laid off is doomed to poverty. At no moment does Sandra consider the possibility of looking for work elsewhere. Yes, it’s easy to say when it concerns someone else, but many of us have been there. If it had at least been considered, it would have made the world of Deux Jours; Une Nuit a bit less dismal but real, instead of unrelievedly dismal but also a bit phony.

What limits the film even more is the ideological lid on the Dardenne brothers’ conception of how the world works. A well-known economic fallacy is that there’s a fixed pool of jobs. This reasoning was used to keep women and minorities out of the work force, and still figures in debates about immigration. It results in the idea that a job is for life, and that someone laid off is doomed to poverty. At no moment does Sandra consider the possibility of looking for work elsewhere. Yes, it’s easy to say when it concerns someone else, but many of us have been there. If it had at least been considered, it would have made the world of Deux Jours; Une Nuit a bit less dismal but real, instead of unrelievedly dismal but also a bit phony.

At the end of the film the Dardennes offer up a twist that undercuts what’s come before. If that’s not enough, they then undercut the undercut, which is even less effective because it relates to Sandra’s character, when there hasn’t been any calling into question, any real development of that character.

A film that posits hard choices makes us think of the real choices made in society. This could also be turned back onto the filmmakers. It might be spiteful to say the directors could have hired a talented but out-of-work actress instead of a star like Marion Cotillard who draws box office. On the other hand, it’s amusing to note that the movie’s credits list as a source of financing something called the Tax Shelter of the Belgian Federation.

A film that posits hard choices makes us think of the real choices made in society. This could also be turned back onto the filmmakers. It might be spiteful to say the directors could have hired a talented but out-of-work actress instead of a star like Marion Cotillard who draws box office. On the other hand, it’s amusing to note that the movie’s credits list as a source of financing something called the Tax Shelter of the Belgian Federation.

Production: Les Films du Fleuve, France 2 Cinéma, RTBF, Belgacom, Archipel 35, BIM Distribuzione, Eyeworks

Distribution: Diaphana Films (France), Sundance Selects (US). Wild Bunch Distribution (worldwide)

More in film review, French film