The Daisy Tannenbaum Misadventures: Author J.T. Allen Shares Paris Favorites

Looking for a good read this autumn? Fans of the Daisy Tannenbaum misadventures will be thrilled to learn of the release of the latest novel. Following Daisy and the Pirates and Daisy in Exile, the saga continues on November 1 when Daisy and The Missing Mona Lisa hits the bookshelves. If you’re not already familiar with this fun series (psssst. It’s not just for kids!), here’s the skinny about the fearless heroine. Daisy, age 12, American girl in Paris, is the precocious, often-snarky narrator — she gets expelled from school for punching a bully and sent to live with her expat aunt in Paris while her mother struggles through a difficult pregnancy. Tales of mystery and derring-do await!

This delightful personality is the creation of award-winning screenwriter, J.T. Allen, who sold his first script while living in Paris and then moved to Los Angeles where he wrote several early drafts of “The Lion King” and “The Preacher’s Wife.” TV movie credits include TNT’s “Geronimo” and “The Good Old Boys”, FX’s “Redemption” and CBS’s “Death in Paradise.” Fun fact: The first Daisy Tannenbaum Misadventure, Daisy and the Pirates, started as a pitch for a Disney Channel movie. The second in the series started as Daisy’s blog, “My Stupid Journal”.

Recently Bonjour Paris connected with J.T. Allen to learn more about his writing and what he loves about Paris. But first, here’s the summary of Daisy and The Missing Mona Lisa. Want to know more? You can read chapter excerpts on the official website.

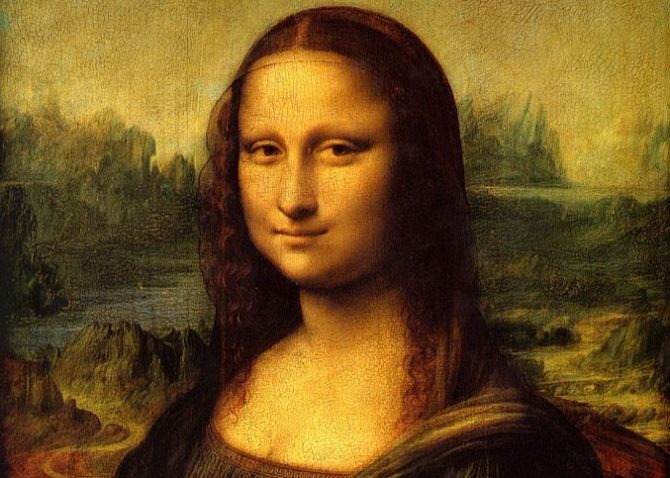

Daisy Tannenbaum heads to a château in the Loire to help her Aunt Mill’s friend, former-spy Felix, catalog his art collection. When Daisy receives a copy of the Mona Lisa as a thank you gift from Felix, strange things happen. This Mona is not just any copy, it’s one of two perfect forgeries created to fool the Nazis during their hunt for the real Mona Lisa in WWII. Daisy’s best friend from the states, Lucia — a newly minted teen model, in Paris to audition for the spring runway shows — thinks Daisy’s Mona is the real one. Real or not, it’s worth a fortune, and when Felix suddenly dies, his family accuses Daisy of stealing it. Daisy must navigate a world of scheming, frequently criminal adults, not to mention traveling ghosts, ginormous pigs, testy lawyers, and obnoxious fashionistas, all to keep her beloved Mona.

Mona Lisa. Public Domain

Bonjour Paris: What were your inspirations for the books?

J.T. Allen: My two daughters at Daisy’s age: their wicked sense of humor, the way they argued with each other and with me. It was easy to create Daisy’s voice, because my daughters frequently barged into my office or sparred outside my door. They read the early manuscripts and would recommend dialog changes with, “Dad, no kid says that.”

Also, my grandmother. She took all her grandchildren to Europe. I was 10. My cousin, same age, was my partner on the trip. This was at least the eighth trip to Paris for my grandmother. She’d sleep in, getting up long enough to hand us Metro tickets and a pocket full of francs, saying, “Go explore. Be back by dinner.” It was brilliant. We had the run of the Metro and the city. That freedom and mobility is instrumental to the Daisy stories.

Then there’s Paris of course. My wife and I lived there in the mid-80s, me collecting rejection notices, she working as a translator and legal secretary for two French attorneys (one of them a young lawyer named Christine Lagarde). I’ve always felt that Paris is two cities: the one you walk around in, that people work in, commute in, and the ghost town. Occasionally you’ll find a fake plaque put up by some prankster that reads, “Personne célèbre jamais habité ici.” (No one famous ever lived here.) It’s not true. Someone famous did. Probably two or three did. Often a dozen did. Paris is so full of the ghosts of the renowned, notorious, and distinguished, not to mention noteworthy, radical, and bizarre, that the ghosts get into traffic jams. That Paris may be mostly in our heads, but everyone carries some variation of it with them. This idea weaves itself through the Daisy books.

View of Paris. Creative Commons

BP: Can you share some of your favorite addresses in Paris?

J.T Allen:

Place de la Contrescarpe, in the Fifth.

Jostle north through the market crowd on rue Mouffetard and you end up at Place de la Contrescarpe, which manages to remain disreputable no matter how many coats of paint they apply. The center circle, with its lackluster fountain, is ringed by concrete teeth to keep trucks from plowing through the middle. Place Vendôme it is not. Nor is it a place to avoid tourists and students. But ringed by cafés, you’ll always find a sunny side of the street to sit down. And every time I’ve gone, I’ve found myself in conversations with complete strangers. Last time it was with a French Legionnaire, white kepi, pressed khakis, enjoying une grande chope and some sunshine on a two-week leave. We talked, mixing English and French. He’d been in Afghanistan and spoke highly of the Americans he served beside. They were reliable and knew their trade, he said. I suspect he would rather have been picking up girls, but he seemed to know how to take life as it came and had picked the right spot to do it.

With a French Legionnaire on the Place de la Contrescarpe, courtesy of J.T. Allen

Place de Vosges, in the Third/Fourth.

This is where the whole “modern” public space thing started in Paris. On the outskirts of the medieval city, Henri IV built matching facades and a shaded archway, behind which the right set could design and build lavish apartments. The central space had no landscaping back then and was big enough for a joust or parading your favorite cavalry squadron. I’ve always adored the fake orange brickwork. Venice was all the rage in 1605, and Venetian bricks were expensive to get in a limestone city, so they just painted them on. Place de Vosges is at the edge of the Marais, which can feel claustrophobic at times, so the park in the center is a shady place for a picnic or reading a book, with Ma Bourgogne on one side and Café Hugo on the other if your picnic basket gets overrun by ants. Louis XIII, whose statue adorns the center of the park, was not particularly popular, apparently, so he and his horse have been torn down and replaced so many times after revolutions, republics, restorations, and so forth, that everyone forgot why they disliked him and finally left him standing. Eventually the Sun King decided to move the party to Versailles, so Place de Vosges lost its vogue and actually looked pretty dog-eared until a decade or so ago, but it has always had beautiful bones, and is a near perfect lingering spot on a sunny day.

Place des Vosges. Photo credit: Marko Maras/ Flickr

Place Vendôme, in the First. (The Hemingway Bar at the Ritz.)

As public spaces go, Vendôme is the Tale of Two Cities counterpart to Contrescarpe. Elitist from inception, planned and financed by cronies of Louis XIV, continuing the idea of building a uniform façade behind which nobles and the well-connected could build whatever hôtel they desired. It’s always seemed a little sterile to me, a place to drill your grenadiers. But whenever someone who has never been to Paris asks the wife and me where to go at night, we usually advise the Hemingway Bar at the Ritz. Be prepared to pay through the nose, we say, but know that you can linger. We used to get dressed up and make an evening of one cocktail when we were low on funds. The barkeeps never seemed to mind. Wood paneling, cozy seats, soft lighting. We saw Serge Gainsbourg roll in one night and play a set at the grand piano. I won’t say that you will always spot a celeb there, but the odds are good. And no friend we’ve directed to the Hem Bar has ever gotten lost on the way. Usually, they report meeting someone who they spent the whole evening with. But if you absolutely gag at the site of Hemingway photos, you might want to avoid the place.

Place Vendôme reflection, courtesy of J.T. Allen

Jardin du Palais Royal, in the First.

Of all the public spaces in Paris, Palais Royal has one of the most riotous histories, though it can seem now, especially at the back, like a sleepy, slightly neglected place to walk your dog. It remains one of my favorite spots in Paris. Cardinal Richelieu built a palace here, which fell into the hands of an assortment of princes, until one of them, Philippe d’Orléans, became king, refused to move to Versailles, and made the court come to him. His great grandson, another Philippe, impish and heavily in debt, borrowed on his name and turned the place into high-priced condos enclosing a garden, with luxury shops on the arcade level. The beauty was that city laws and curfews didn’t apply on the grounds, so the place became a mini-Vegas, complete with gambling, hookers, late night bistros, concerts, acrobats, and attending thieves, pickpockets, and syphilis. Vast fortunes were lost at the gambling tables, the Gluckists and Piccinnists (vying music factions) had a brawl here, the Jacobins planned a revolution at one of the cafés, and poor Philippe, a gracious host, was guillotined anyway. Later it settled into a quieter quarter where Colette actually did walk her bulldog, Toby Chien.

Palais Royal reflection, courtesy of T.J. Allen

La Pagode, in the Seventh

More of an interior public space, the grand high temple of French cinema, La Pagode, ironically situated at 57 rue de Babylone, is actually closed at the moment but rumor is it’s being refurbished and will open again soon. I’m holding my breath. La Pagode was built in 1896, when all things Japanese were the craze, as a playhouse for the owner of Le Bon Marché’s wife. Buddhist monks might be puzzled by the neo-rococo interior, the art nouveau stained glass, and the panels of elaborate Asian battle scenes, but the place became the party space of the Paris elite until a younger man, a bad divorce, and the end of an era took their toll. (See Bonjour Paris’s terrific article about La Pagode by Dorothy Garabedian.) It wasn’t opened to the riff-raff as a cinema temple until 1931, and since then has been an art house venue frequented by the avant-garde (Picasso broke up with Dora Maar during a matinee) and later by the Nouvelle Vague. It closed in 2015, but despite that, and unknown to most, Paris remains the best place in the world to see films from all over the world, in all styles, all languages, from all periods. La Pagode is a jewel in the crown of a city rich in cinema history and my favorite film palace on the planet.

La Pagode in the 7th arrondissement of Paris. Photo: Dorothy Garabedian

Lead photo credit : Books by J.T. Allen

More in author, author interviews, Daisy Tannenbaum Misadventures, J T Allen, jardin du palaid royal, La Pagode, place de la contrescarpe, Place des Vosges, Place Vendôme