Nicolas Flamel: The Medieval Alchemist in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Well before water was miraculously turned into wine, ancient alchemists claimed to have discovered the secrets of turning base metals into gold and prolonging the life of any person who consumed the elixir of immortality. The very word alchemy conjures up images of wizards and witches bent over bubbling cauldrons. Perhaps the most famous fictional alchemist was Merlin, the wizard who helped King Arthur create Camelot over a thousand years ago.

However, before Foucault’s Pendulum by Umberto Eco, The Egyptian Secret by Javier Sierra, Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books were written, a real alchemist living in medieval Paris purported to have uncovered the arcane mysteries of “The Philosopher’s Stone” deciphering the recipes for immortality and turning lead into gold.

The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone. © Public Domain

Nicolas Flamel is thought to have been born in 1330 in Pontoise, a northwestern suburb of Paris in the Val d’Oise region. He spent his adult life in Paris as a bookseller, manuscript copyist, and notary. He married a woman by the name of Perenelle in 1368. There are scant details about her birth and early life. She outlived two previous husbands and brought their fortune to the marriage. She and Flamel were devoted Catholics, contributing financially to churches and almshouses for the poor. Like her husband, she developed a reputation as an alchemist.

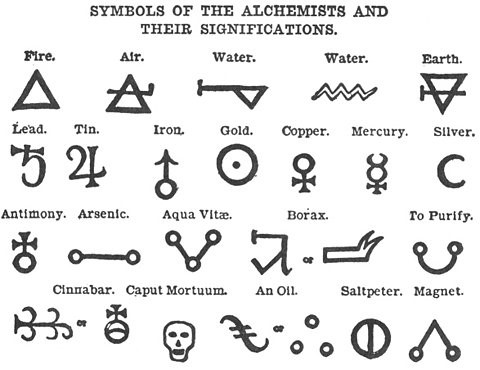

By the 12th century, European scholars had begun to translate the alchemical corpus of Greek and Arabic cultures, introducing them to the term al-kimiya. From this newfound knowledge, a dynamic literature emerged, dealing with alchemical techniques for dye-making, distilling, metallurgy, mineralogy, and the transmutation of metals. Flamel’s trade in books brought him familiarity with these ancient writings. The art of alchemy eventually gave birth to astrology, astronomy, cosmology, biology, medicine, chemistry and physics. Although these modern sciences took on a life of their own down through the ages, many have remained true to the original ideals of the early alchemists.

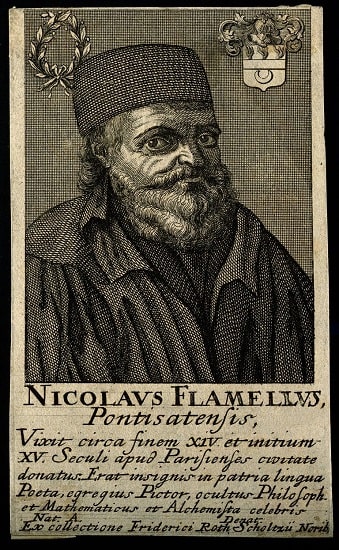

Nicolas Flamel. © Public Domain

According to legend, one night Flamel had a vivid, unsettling dream in which an angel appeared to him. The angel gave him a beautiful book bound with hand-tooled copper, its pages made out of fine tree bark. As Flamel was about to take the book from the angel’s hands, he suddenly awoke from his dreams convinced that this was no ordinary book, that it might contain the very secrets of life. He knew many symbols that alchemists used back then, but the ones in this book were beyond his comprehension.

The following day he purchased a 21-page book from a stranger desperately in need of money. Its copper cover, engraved with strange diagrams and words, was exactly the same one from his dream. Flamel was only able to decipher that the book was written by Abraham the Jew – “a prince, scholar, priest, astrologer, and philosopher.” Because the book had been written by a Jewish scholar, Flamel hoped another Jewish scholar might be able to help him translate it. Unfortunately, religious persecution at that time had driven all of the Jews out of France.

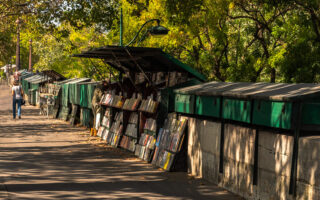

Selection of books. © Susan Q Yin, Unsplash

In 1378, after copying a few pages of the book, Flamel and Perenelle joined a pilgrimage to Spain, where many exiled Jews had settled. Once in Spain, they quickly discovered that no one was eager to help them. Eventually, they were offered an introduction to a very old, well-educated Jew by the name of Maestro Canches who lived in the northwestern Spanish village of Léon. Canches, too, was not eager to help them until they mentioned Abraham the Jew. He had heard of this great sage who was wise in the mysterious teachings of the Kabbalah. Canches was able to translate the few pages that Flamel and Perenelle had brought with them. He wanted to return to Paris with them to examine the rest of the book, but Jews were still not allowed in the city. Sadly he died before he could help them any further.

Flamel and Perenelle returned to Paris. They made it their life’s work to fully understand the text of the mysterious book Flamel had purchased. By 1382, they allegedly decoded enough of the book to successfully create “The Philosopher’s Stone”, an alchemical substance, most likely red sulphur, capable of turning base metals such as mercury and lead into silver and gold.

Ground floor facade and a detailed view of its inscription and door jambs. © CC BY 2.0

After Pernelle’s death in 1397, Flamel’s wealth came under suspicion. Historic records show that he continued to make generous donations to churches, build almshouses for the poor, and establish free hospitals. Virtually none of his wealth was used to enhance his own style of living, but was used exclusively for charitable purposes. However, the question remained, had he indeed succeeded in the transmutation of metals?

In 1407 Flamel commissioned a four-story house to be built at 51 rue Montmorency in what is the 3rd arrondissement today. Notably, it is the oldest stone house in Paris. It’s said that it was here Flamel carried out his experiments in alchemy. Strange symbols adorn its facade: the three door jambs are decorated with sculptures framed in basket-handle arches, which depict characters holding phylacteries (small leather containers holding Hebrew texts) or sitting in gardens. The central door is framed by four angel-musicians. Two side-door jambs feature Flamel’s initials. An ornate inscription above the middle door, which includes the date of construction, was fully restored by the city of Paris in 1900. Just below the ground floor cornice is an inscription in Middle French:

Symbols of the alchemists. © Public Domain

Nous homes et femes laboureurs demourans ou porche de ceste maison qui fut faite en l’an de grâce mil quatre cens et sept somes tenus chascun en droit soy dire tous les jours une paternostre et un ave maria en priant Dieu que sa grâce face pardon aus povres pescheurs trespasses Amen

We, men and women, workers living in the porches of this house that was made in the year of grace one thousand four hundred and seven are, each of us, required by law to say every day one Our Father and one Hail Mary while praying to God that his grace brings forgiveness to the poor deceased sinners, Amen.

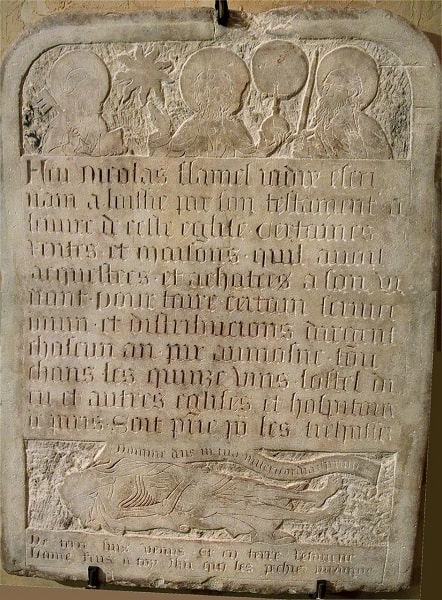

Flamel’s tombstone at Musée Cluny. © Public Domain

Archives say Flamel died in 1418 at the age of 88. Before his death he designed his own tombstone which is now on display at the Musée de Cluny. After his death, the house at 51 rue de Montmorency was ransacked again and again by those seeking “The Philosopher’s Stone,” but it was never found – neither was the copper-covered book of Abraham the Jew. The facade of the building became an historical monument in 1911.

He bequeathed the property to the church of Saint-Jacques-La-Boucherie, where he and his wife were buried. The church was destroyed during the French Revolution, with only its looming Tour Saint-Jacques remaining. (The gothic tower can be visited via guided tour, upon reservation.) Two streets near the tower are named after him and his wife: the rue Nicolas Flamel close to the Louvre Museum intersects with rue Perenelle.

Saint-Jacques Tower. Wikimedia commons

During the 15th and 16th centuries, interest in the occult, and particularly in alchemy, flourished. Flamel’s posthumous re-imagining as France’s most successful alchemist grew with the publication of the Livre des Figures Hiéroglyphiques (Exposition of the Hieroglyphical Figures) in Paris in 1612. It was attributed to Flamel. The publisher’s introduction chronicled Flamel’s lifelong search for “The Philosopher’s Stone.”

The truth of his story was first questioned in 1761 by Etienne Villain. He claimed that the source of the Flamel legend was P. Arnauld de la Chevalerie, publisher of Livre des Figures Hiéroglyphiques, who wrote the book under the pseudonym Eiranaeus Orandus. However, other writers have defended the existing account of Flamel’s life. By the mid-17th century, Flamel had achieved legendary status within alchemy circles including references in Isaac Newton’s journals to “…the Caduceus, the Dragons of Flamel.” In the 19th century, Victor Hugo referenced him in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Book cover for the UK and English version of the Harry Potter book. © Wikipedia

The composer Erik Satie was also intrigued by Flamel, and Albert Pike, an American Confederate General during the Civil War, referred to Flamel in his book Morals and Dogma of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. Finally, Flamel became a household name in the 20th century thanks to Harry Potter. In J.K. Rowling’s bestselling novel and film adaptation Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Flamel’s reputation as an alchemist was revived.

Lead photo credit : Flamel house in Paris. © Public Domain

More in architecture, book, history, Paris, science

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY