Interview with Therese Ann Fowler on “Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald”

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The opening of Baz Luhrmann’s film, The Great Gatsby, has reignited the publishing world.

Sales of the book are again topping bestseller lists, and creating renewed interest in the classic American tale. In fact, it was Zelda who suggested F. Scott to name the novel The Great Gatsby over other potential titles like Trimalchio of West Egg.

Zelda Sayre met F. Scott Fitzgerald in her hometown of Montgomery, Alabama in 1918. The couple fell in love, to the chagrin of her father, and their story became legend.

Zelda Sayre met F. Scott Fitzgerald in her hometown of Montgomery, Alabama in 1918. The couple fell in love, to the chagrin of her father, and their story became legend.

The Fitzgeralds moved to Paris in the 1920s, joining American expatriates to become part of “The Lost Generation,” along with Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway. (Zelda and Hemingway despised each other).

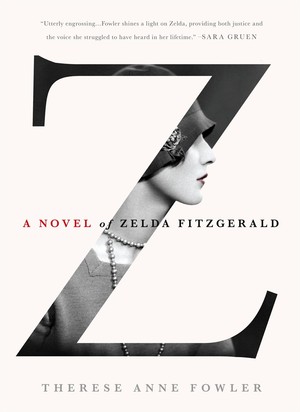

Author Therese Ann Fowler explores the Fizgerald’s time in Paris and beyond, in her much buzzed-about book, Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald, which debuted at #10 on The New York Times Bestseller List and garnered much media attention from The Wall Street Journal, the Kirkus Reviews and more.

Author Therese Ann Fowler explores the Fizgerald’s time in Paris and beyond, in her much buzzed-about book, Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald, which debuted at #10 on The New York Times Bestseller List and garnered much media attention from The Wall Street Journal, the Kirkus Reviews and more.

Like many, I had a specific view of Zelda: She’s the charming, imbibing blond in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. She’s a crazy woman and a distraction in Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. But Fowler presents a different look at Zelda; one that’s far more interesting than Zelda’s stereotype in the literary world.

Fowler’s engaging story of Zelda takes the reader on a romantic, turbulent, adventurous ride through one of literary history’s most notorious figures. Like most notorious figures, the line between rumor and truth is often blurred. Fowler clears the line, and the reader dives into the truth of Zelda; her story, her intentions and her love.

As Bogart says to Ingrid in Casablanca, “We’ll always have Paris.”

Zelda and F. Scott will always have their time in Paris. And luckily, we will too.

I was fortunate to have the chance to speak with Ms. Fowler about her debut novel.

1. You discovered that your mother and Zelda Fitzgerald both passed away on the same date. Was this the catalyst to write about Zelda?

In a way. What that uncanny coincidence did was compel me to consider the idea more thoroughly, because my initial reaction had been resistance. I’d thought of Zelda as nothing more than the disruptive, spoiled wife of one of literature’s most beloved authors, the woman who’d driven him to drink, derailed his career, prevented him from achieving his potential. As my research began to uncover things that conflicted with my original perception of Zelda, I became intrigued with the question of why that perception persists in popular culture. That led me to learn even more, and eventually led to a point where the prospect of writing about her became irresistible.

2. You researched over 20 books about the Fitzgeralds in writing Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald. What is one of the most surprising things you learned?

The biggest surprise was the discovery of how large a role Ernest Hemingway played in the Fitzgeralds’ lives. His influence altered things dramatically, and in ways I couldn’t have guessed.

3. Zelda’s review for The New York Tribune of The Beautiful and Damned, F. Scott’s 1922 novel which sampled Zelda’s writing, caused a rift with her and F. Scott. Do you think their marriage stifled Zelda’s creativity?

The story of that review causing a rift is, as best I can determine, a fabricated one. Zelda gave her diaries to Scott quite willingly and was pleased, at the time, that he was using her earlier escapades as material for his stories. The remark about plagiarism in that review is very tongue-in-cheek—she’s teasing him. It’s only years later, when she is working on a novel of her own, that the question of who “owns” their joint experiences and is entitled to use them becomes problematic.

Scott had a role in stifling Zelda’s creativity, certainly, but so did her doctors and so did the culture of the time. She played a role in it herself. It’s a fascinating and complicated matter that needs to be seen in context.

4. In Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, he makes his disdain for Zelda very clear. Why do you think Hemingway disliked Zelda?

Here, too, is another complex matter. They were originally quite friendly to each other, but then something occurred that changed the dynamic between them. I’ve given a version of what that something may have been in my novel, but as I don’t want to spoil things for readers who haven’t yet had a chance to read Z, I’ll refrain from saying more.

5. As chronicled in A Moveable Feast, the Fitzgeralds, like Hemingway, were heavy drinkers and lived a lavish, party-filled life in Paris. How do you think Paris affected Zelda?

The lifestyle they lived in Paris (and elsewhere) made it easy, at first, for Zelda to overlook or ignore the growing troubles in her life. By the time those troubles could no longer be ignored, they had become too overwhelming to manage, and Zelda suffered a breakdown a few months before her thirtieth birthday.

The Parisian arts scene seduced her as much as the party scene did, though, and those influences would lend themselves to the one talent that would carry her through her illness and beyond: her painting.

6. There is a lot of media attention on your novel Z. Do you feel pressure for your work to perform a certain way?

No, strangely enough, I’m not overly concerned. My part of the job was done when I turned in the last of the revisions to my editor; what becomes of the book is out of my control. The media attention has been remarkable, though, and I’m grateful for the way it’s continuing to help Z find her readers.

7. Baz Luhrmann’s new film, The Great Gatsby, is highly-anticipated. The novel’s character Daisy was inspired by Zelda. How much of Zelda is characterized in Daisy?

This belief that Zelda inspired Daisy is another persistent misconception—a declaration made who knows how long ago that has been repeated so often that it’s considered truth. The main thing the two have in common is that they are Southern women of some prominence. But unlike Daisy’s family, Zelda’s family was not wealthy, and Zelda would never have been capable of behaving as coldly as Daisy does at the end of The Great Gatsby (though if she had been, much would have been different, perhaps better, in her life). A careful reader will see more of Zelda’s personality in Jordan Baker.

8. Have you been to Paris, and if so, what is your favorite memory of Paris?

I’m very sorry to report that I haven’t yet been there, but I’m dying to go!

9. As a girl, you successfully campaigned to play on the boys’ Little League Team, and you were one of the first girls in the U.S. to do so. Zelda was also an athlete, spending her youth as a swimmer and dancer. Do you identify with her energetic spunk and zest for life?

I do, yes. I was very much like Zelda in my youth, though I didn’t have her advantages (that is, she was the daughter of an associate Alabama Supreme Court Justice, and so was considered to be part of Montgomery’s upper class). I was on the go all the time, involved in pranks, at ease with boys and girls alike, outspoken, unconventional in my attitude about rules. And as an adult, people tell me I make a lively addition to certain social gatherings—though my behavior is never so outrageous as Zelda’s sometimes was. The voice of caution resides in me in a way I think it rarely did for her.

10. What advice would you give aspiring writers?

The most important thing aspiring writers must do is read. The next most important thing they must do is write. Sounds incredibly basic, I know, but you’d be surprised by how deficient many are in these two areas. What a lot of aspiring writers actually want is to have written–that is, to be an author, as opposed to being a writer.

There’s no single path to success, but the one thing all successful writers have in common is persistence, and the willingness to devote themselves to improving their craft even after initial successes come along. Also, aspiring writers should learn to embrace revision like a lover. The writing profession requires an ability to accept criticism and to work collaboratively with editors. Everything can be improved, given sufficient time and consideration.

More in book preview, f scott fitzgerald, Interview, new book, Paris books, The Great Gatsby, Therese Ann Fowler, Zelda Fitzgerald