Around the World in 80 Days

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Rumor has it that the 11-year-old Jules Verne tricked his way aboard the sailing ship Coralie with the aim of traveling to the West Indies to bring back a coral necklace for his much-beloved cousin. Verne’s father managed to catch him at the harbor before the ship set sail. He made his son promise to travel “only in his imagination.” This childhood feat of derring-do may have really happened, but this tale is thought to be largely embroidered upon by his biographer, his niece Marguerite. Like Jules Verne’s biography, his tales have been elaborated upon but that doesn’t make them any less intriguing or entertaining.

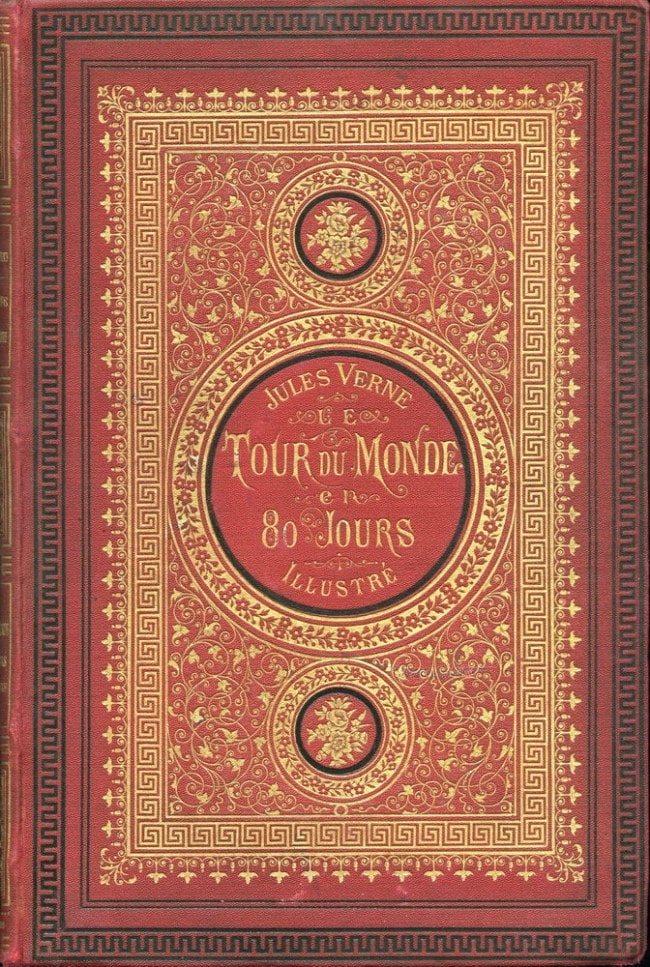

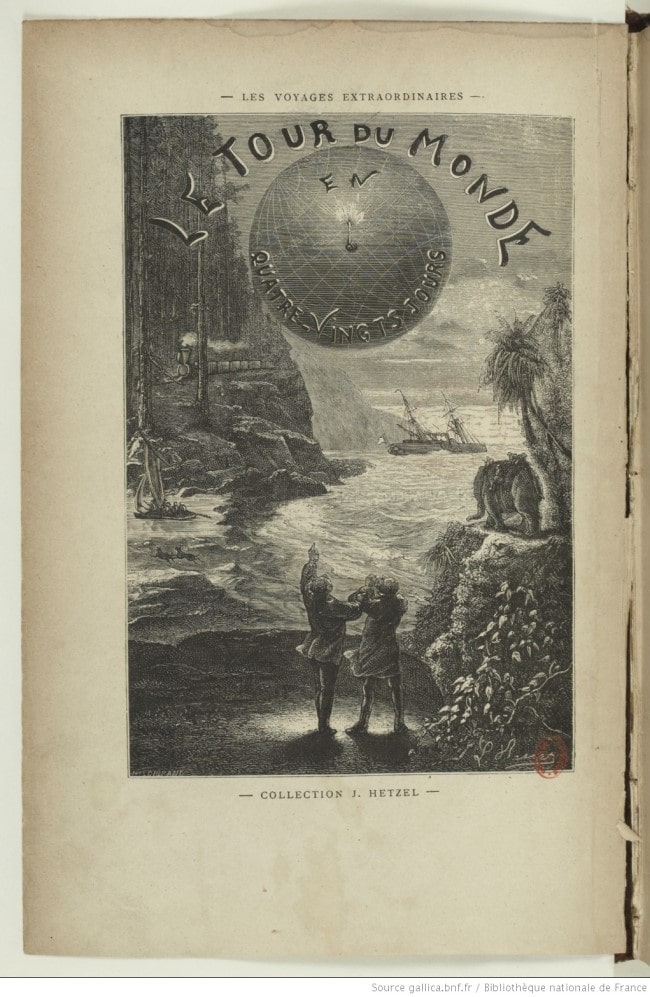

The French author who grew from that adventurous little cabin boy wrote Around the World in Eighty Days or Le Tour du Monde en Quatre-Vingts Jours, in 1872 in serial form for the newspaper Le Temps. Verne’s most successful tale has been craftily remade as a TV series and premiered on BBC on December 26, 2021 and on PBS Masterpiece on January 2, 2022. David Tennant of Doctor Who fame knows how to portray time travel will be a fine Phileas Fogg. However, it seems that the remake will be a kaleidoscopic collage of the original story.

An adventurous tale

Phileas Fogg, the lead character in Jules Verne’s adventure, was an Englishman of meticulous habits. The well-regulated Fogg kept to the same schedule. His habits were unchanging and he was never late. Apart from his daily hand of whist, he played his cards close to his chest. Fogg’s fellow members of the Reform Club had no inkling how he made his fortune or how he passed his time. There was conjecture among the Reform Club members that Fogg had traveled far and wide because no one was more familiar with the world than he. But perhaps Fogg was only an armchair traveler; apart from his daily sojourns to the Reform Club, he seemed not to travel beyond the front door of his own house.

Phileas Fogg, an ilustration from the novel “Around the World in Eighty Days” by Jules Verne, painted by Alphonse de Neuville and or Leon Benett. © Wikimedia Commons

Fogg’s luxurious mansion wasn’t decorated in any anticipated steampunk kind of way. The Savile Row address had no study and there were no books. There were no models of wildly inventive flying machines with gears and cogs. There was nothing copper or riveted or strangely submarine in Fogg’s house. But there was a clock. Fogg was in possession of a complicated clock which indicated the hours, minutes, and seconds as well as the days, months, and years. Jules Verne described Fogg as being as regulated as a “Leroy” chronometer.

For such an automaton, the clock was an accurate metaphor for Fogg. Fogg’s new valet Passepartout soon found out his daily routine was to the minute, “toast and tea at twenty-three minutes past eight, the shaving water (at 86º) at thirty-seven minutes past nine.” Passepartout found his new boss to be “A real machine. Well I don’t mind serving a machine,” he said.

Passepartout as illustrated by by Neuville and Benett in “Around the World in Eighty Days”. © Wikimedia Commons

Passepartout was a Frenchman who held a variety of jobs. After a venturesome life as a vagrant, singer, circus performer, and firefighter, he was eager to settle down and lead a more tranquil life as Fogg’s domestic help. However, to Passepartout’s dismay, the very day he was hired, Fogg uncharacteristically embarked on a massive undertaking. He and his fellow members at the Reform Club entered a debate as to whether or not, with new advances in technology, the world could be circled with greater ease. The very precise Fogg wagered that he could make that journey in 80 days or less. The bet was for the sizeable sum of £20,000, half Fogg’s fortune and the equivalent of a whopping 2 million pounds.

Brought along on Fogg’s journey is Passepartout, whose clever name means “goes everywhere,” or “master key.” Passepartout’s colorful past proves to be useful on their travels as he is able to creatively solve the obstacles that they encounter.

The author’s boundless imagination

Like Phileas Fogg, Jules Verne (1828-1905) spent much time in a club-like setting, attending sessions of the Geographical Society in Paris where he was an honored member. Here among the society’s library and private collections, Verne found materials necessary for the scientific preparation of his writing. Yet up against the society of formal geographers, Verne found himself apologizing for the large amount of imagination in his stories.

Jules Verne by Étienne Carjat. © Wikimedia Commons

As a teen, Verne loved writing fantastical stories, but his father sent him to law school to carry on the family tradition. Continuing to write while studying law, Verne’s family connections ingratiated him in the circle of Parisian literary salons. A well-known palm reader introduced Jules to the Dumas, père et fils. The patriarchal Dumas secured Verne a meagre position at the Théâtre Lyric where he had a successful run as a playwright. He carried on writing short stories and in 1851 Verne’s first historical adventure appeared in print.

Writing came easily to him and Verne was considered marvelously gifted. Yet, as it is with most men of arts and letter, Verne’s father wanted him to find a real job. In 1856, the newly married Verne, became a stock broker at Eggly & Cie where he split his days between the stock market, his theater friends, and collecting scientific and historical facts for his side career as a writer.

In 1863, Verne wrote his first full-length adventure novel enabling him to combine the theme of travel with his detailed historical research. Verne’s success with the book Five Weeks in a Balloon guaranteed that he would be able to leave his position as a broker and concentrate on writing.

Jules Verne, Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours. © Wikimedia Commons

Verne had formulated a new kind of novel, a roman de la science (novel of science). Over the next decade Verne wrote many successful stories, the most notable being Journey to the Center of the Earth and Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Around the World in Eighty Days was written during unsettling conditions, both for France and Jules Verne. He began the story during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). Even though he was a family man of 42, he was conscripted into the army as a member of the coast guard. The disastrous outcome of this conflict led to the Paris Commune. Money was tight, his royalties weren’t being paid, and his father had recently died.

In Episode 1 of the current remake, the filmmakers emphasize the strife of the Paris Commune. Despite Verne’s difficulties at the time, Verne didn’t describe the insurrection. In fact, Verne only makes a fleeting reference to France from the point of view of Passepartout as a returning Frenchman. The 1872 story spends no time in Europe at all.

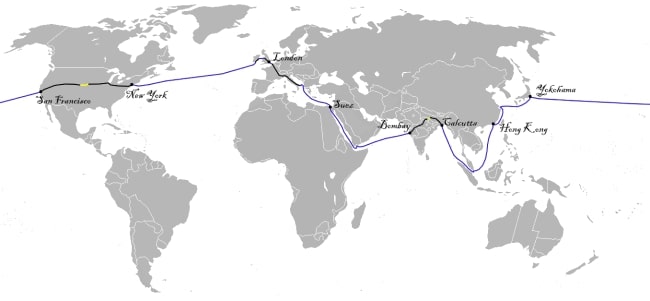

A map illustrating “Around the World in Eighty Days.” © Wikimedia Commons

The high-jinx in Verne’s story stem from incomplete routes and dead ends: train tracks that aren’t complete and bridges that collapse. Much confusion and conflict arises from misinterpretations of customs and traditions that Fogg isn’t used to. The 19th-century story contains interaction with locals that just wouldn’t be appropriate in today’s environment. Perhaps this is the reason why some details and characters have been freely changed for this new version.

One example in the adaptation: The duo’s female companion is a strong journalist named Abigail Fix. She takes her name from the original Scotland Yard Detective Fix who was bent on pursuing Fogg as an escaped bank robber.

Verne’s characters employ steamships, trains, and sail-powered sleds to get from location to location. But no balloons. None.

Jules Verne’s characters certainly did travel aeronautically in his novel Five Weeks in a Balloon but not in Around the World in Eighty Days. The fact that Verne’s publisher produced a book with a balloon on its cover did nothing to stop this trope. The 1956 Hollywood remake of Eighty Days, starring David Niven as Fogg, made it seem that the hot air balloon was central to Verne’s story – it wasn’t. The balloon was used as a vehicle, per se, to show off exotic locations in large format on the studio’s new curved screen technology.

Around the World in 80 Days, © PBS

Jules Verne’s adventure was published as a serial in Le Temps. The date of first installment of the serial publication was the same date as the newspaper – October 2, 1872. Some readers believed that the global journey was actually happening; bets were placed. Some railway and shipping companies lobbied Verne to appear in his tale.

Though a mixture of fantasy and fact, Verne never admitted to having had a specific model for the hero of his story, but two men might have been the inspiration. In 1870, the eccentric Boston entrepreneur George Francis Train toured the world in almost 80 days. Train later claimed, “He stole my thunder. I’m Phileas Fogg!” In 1872, William Perry Fogg published a book called Round the World: Letters from Japan, China, India, and Egypt that chronicled a slower 1868 tour. Coincidence – I think not.

George Francis Train. © Wikimedia Commons

Verne’s 80-day timetable may have been decided on from a similar one that appeared in the Magasin Pittoresque after the construction of the Suez Canal, the American transcontinental railway and the Trans-Indian Peninsular Railroad. The periodical Le Tour du Monde contained a short piece on October 3, 1869 titled “Around the World in Eighty Days,” which referred to the patch of incomplete railroad between Allahabad and Bombay, an important point in Verne’s work.

Le tour du monde. © BNF Gallica

In fact the 80-day milestone was advertised in British and Irish newspapers the year that Verne began his book. I found that the Belfast Weekly News surmised that “tourists traveling continuously without any stoppage can now go around the world in eighty days, making the entire journey by rail and steam ship and going by way of Liverpool, the Suez Canal, Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong, Yokohama, San Francisco and the Pacific Railway.” This is startlingly similar to the itinerary that Verne worked out for himself.

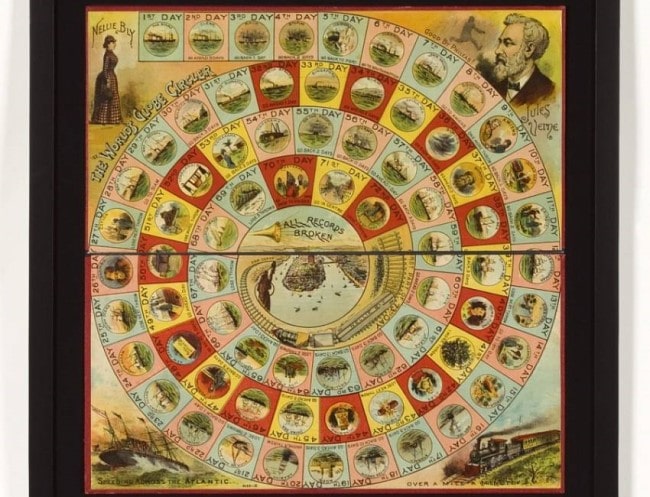

Verne’s novel made 80 days the time to beat and inspired numerous attempts to travel around the globe in even less time. The most notable attempt was by American journalist Nellie Bly, who in 1889-90 managed it in just 72 days. And the affronted George Train reduced the time to 60 days in 1892.

Jules Verne’s book was a window to the future. It was now a world in which global tourism could be enjoyed in relative comfort and safety. Once a feat reserved for heroic and hardy adventurers, anyone with a spark of imagination, and a pocket full of money, could draw up a schedule, buy tickets, and travel around the world.

The book of Around the World in Eighty Days published in 1873 sold nearly half a million copies during Verne’s lifetime. With translations in English, Russian, Italian and Spanish, the plot and lively narrative won Verne worldwide renown, and is still as intriguing today as it was 150 years ago.

Lead photo credit : The "80 Days" board game. © Google Arts and Culture

More in books, French history, history, Le Tour du Monde

REPLY