The Story Behind Chagall’s Stunning Ceiling at the Paris Opera

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

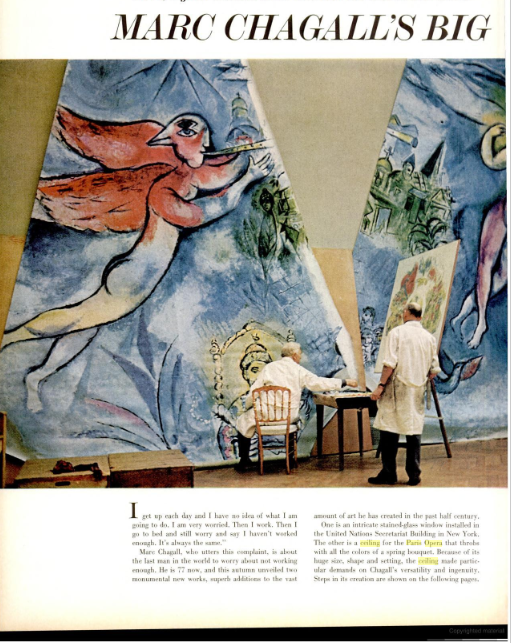

It’s beneficial to have friends in high places. Two such friends who found themselves in rarified air were the Russian expat artist Marc Chagall and André Malraux, award-winning novelist, theorist and statesman. Close friends since 1924, Malraux was a 20-something surrealist poet when he met Chagall at his first exhibition of paintings. Fast forward to 1962 and Malraux as the minister of cultural affairs under de Gaulle, commissioned his friend Chagall to create a new ceiling for the Paris Opera.

Marc Chagall, around 1920, photographed by Pierre Choumoff. Public domain

Designed by Charles Garnier, the Palais Garnier opened in 1875. Like a gigantic treasure chest, the imposing Paris Opera was one of the major edifices that anchored the renovated streets of Paris. Attending the Palais Garnier in the early 1960s, André Malraux was disappointed with the opera house’s ceiling. The floating cherubs in Jules-Eugène Lenepveu’s original trompe l’oeil were fantastic and in keeping with the other gilded semi-nudes festooning the interior. However, Malraux thought these putti in their pastel heaven represented a bourgeois taste no longer relevant to Paris of the 1960s. Wearing his “art theorist hat,” Malraux once argued that art transcended time, but he also believed that when a work had fallen into obscurity a process metamorphosis was needed. Malraux wanted the ceiling repainted.

Behind closed doors, Malraux gave the commission to repaint the ceiling of the Paris Opera to his friend Marc Chagall. No other tenders were entertained. The press and critics balked: the diamond in the crown of Paris’s arts and culture had been given to Chagall, a foreign-born, Jewish, avant-garde artist. Nevertheless, Malraux countered his naysayers, shrugging in his ever-so French way that, “the ceiling will be repainted by Chagall or we shall close down the Opera.”

At first Chagall was reticent. He was 77 and plagued by a bad back. The dissension from his critics pierced him, adding to the anti-Semitic barbs that Chagall had endured his whole life. However, his wife Vava, in accord with Malraux’s wife, urged him to go ahead.

André Malraux, Prix Goncourt. Photo credit: Agence de presse Meurisse/ BNF Gallica

Luckily, Chagall was a natural choice. He understood theater and knew what was needed. He had assisted in producing set designs for the Ballet Russes and for the Moscow State Jewish Theater. In New York in 1945, Chagall produced the sets and costumes for the Metropolitan Opera’s production of The Firebird. In 1958, Chagall designed the sets and costumes for Daphnis et Chloe in the Opera Garnier.

Chagall refused payment for his ceiling design. The French State covered only the cost of Chagall’s materials. Fortunately for his back, Chagall didn’t paint the work in situ like Michelangelo. The work on the 2500 sq ft canvas was carried out at the Gobelins tapestry factory with the help of two young underpainters. With fresh flowers in his studio and Mozart on the turntable, Chagall dedicatedly worked all day, with little to eat or drink. He was so vigorous he could destroy a brush within 15 minutes.

Palais Garnier. Photo credit: Alexander Hoernigk / Wikimedia commons

Freedom of color was characteristically Chagall. The light hues of post-war France contrasted with his memory of the browns and greys of his oppressive Russian homeland. Chagall had a mystical spirit believing love was the force that bound the universe together. Similarly, Chagall’s new subject matter would have to flow into one entity; on the rounded ceiling there would be no beginning or end. The circular design of the ceiling roughly takes shape in a flower, made of five petals of different colors.

Each petal-like shape refers to composers in the opera’s repertoire, and references Paris with architectural landmarks. In her 2019 book The Art of Looking Up, Catherine McCormack explains what each petal segment represents.

The white petal honors the composers Rameau and Debussy. André Malraux looks out from the window in an episode from Debussy’s ballet Pelleas et Melisande. This is a throwback to the tradition in Renaissance painting of including portraits of patrons. Included is a self-referential image of the Opera Garnier itself.

The green petal is devoted to lovers: Wagner’s tragic Tristan and Isolde, and Berlioz’s symphony, Romeo and Juliette. Included are the Place de la Concorde and the Arc de Triomphe. Chagall loved these Paris monuments, stating, “My art needs Paris as a tree needs water.”

The ceiling by Chagall at the Paris Opera, with chandelier. Photo credit: 139904 / Wikimedia commons

In the center of the blue petal, a saucy angel shows us works from both Mozart and Mussorgsky. An homage to Mussorgsky shows an episode from his opera Boris Godunov, where Boris the Tsar perches on his throne. Rendered in green is the city of Moscow. The angel holds a garland with a portrait of Mozart. For Chagall, Mozart was divine, and for him the Magic Flute was the height of spiritualism. We can see a small bird with a flute, perhaps representing the bird catcher Papageno.

In the happy yellow segment, peasants from Alphonse Adam’s Giselle dance toward a woman morphing into a swan who represents Tchaikovksy’s Swan Lake. At the top is a surprising angel-musician, whose head and body have become one with a cello.

The red petal honors the Ballet Russes with depictions of Stravinsky’s Firebird and Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe. Near the top is Chagall himself, with his palette and the bird, which is curiously, and contrastingly green. He seems to be plucking its tail feathers for his paintbrush. Here is the the Eiffel Tower and a similarly long figure of a couple both male and female – Daphnis and Chloe – in one body. It’s another of Chagall’s examples of two bodies merging into one. These characters float in perfect harmony above their island home populated with mythological figures.

A separate design was made for the dome’s center from which the infamous chandelier hangs. Surrounding the chandelier are reminders of the famous composers Beethoven, Gluck, Bizet, and Verdi. One doesn’t usually take into consideration that paint has a weight. Chagall used 200kg (440 lb) of paint to complete the mural. That’s meager when compared to the weight of the seven-ton light-fixture it surrounds – the chandelier that writer Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera doomed to fall 20m (65ft) into the audience below.

Chagall worked on the commission from January to August 1964. Chagall’s ceiling was inaugurated on 23 September 1964. The orchestra played the last bars of Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony, the famous chandelier was lit, and the artist’s ceiling came to life. It garnered rapturous applause from the audience.

Chagall ceiling. Credit: Google Arts and Culture

Chagall spoke at the unveiling. “Two years ago André Malraux asked me to paint a new ceiling for the Paris Opera. I was troubled, touched, and deeply moved. I wished to reflect, as though in a mirror high above, a bouquet of dreams, the creation of actors, of composers, to recall the colorful movement of the audience below. To sing like a bird, without theory or method. To render homage to the great composers of opera and ballet.”

The ceiling is like a dream, and opens the rock-solid building into the heavens. Lenepveu’s depiction of heaven is still there, under Chagall’s whimsy of color, music and love. Does the ceiling of the Palais Garnier need to metamorphose again? Have yet another layer added? At 60 years old, I believe Chagall’s work has staying power.

The ceiling of the Paris Opera. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

Lead photo credit : Chagall's ceiling at the Paris Opera. Photo: Hazel Smith

More in André Malraux, marc chagall, Palais Garnier