Suzanne Valadon Finally Gets the Attention She Deserves in Paris

Circus acrobat, sought-after model in Montmartre, eminent artist… The story of Suzanne Valadon is one quite unlike any other. And now it’s in the spotlight in a major retrospective of her work at the Pompidou.

Behind every successful man is a strong woman, or so the old saying goes, and that could hardly be more true than in the case of Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938) and her son Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955). Though it was the latter who achieved arguably the greater fame, it was largely thanks to his mother, who introduced him to painting as a remedy for his worsening alcoholism, that he attained his success. Furthermore, what can also get lost in all this is that Valadon was a trailblazer of the art world in her own right – just for rather different reasons.

While Utrillo is remembered for his atmospheric street scenes of Montmartre, which have come to characterize this famed district, Valadon pushed the boundaries in another direction altogether. More interested in depicting the human body, which she did in a bold, distinctive style that was entirely her own, in 1894 she became the first woman to be admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. She was also one of the first female artists to paint a full-frontal male nude.

Suzanne VALADON. Portrait de Mauricia Coquiot, 1915 Huile sur toile, 91 × 73 cm. Donation Charles Wakefield-Mori, 1939 Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, AM 3800 P, en dépôt au musée des Beaux-Arts de Menton. Crédit Photo : Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/ Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

Consequently, this landmark exhibition at the Pompidou – the first in France dedicated solely to Valadon’s work for almost 60 years – feels somewhat overdue. Before we get to the show itself, though, and the story of her extraordinary career trajectory, first a confession…

I must admit that I, too, have been guilty of overlooking the full extent of Valadon’s talents, dazzled as I have been by those of her son. As a resident of the area just to the north of Montmartre, I have long loved the paintings of Utrillo, who — when he wasn’t drunk, or battling with his fragile mental health — produced some of the most beautiful depictions of the area ever rendered. To my mind, no one captured the magic of Montmartre quite like he did – and, as such, I have spent the last few years collecting every last postcard, book and print that I could find.

I have always felt a strange sort of connection, too, because he and his mother lived in the very neighborhood in which I now reside. Starting out in Rue du Poteau, they later moved into the building that is now the Musée de Montmartre, in Rue Cortot, where today you can see a recreation of their atelier-apartment. Also, Utrillo is buried in the nearby Saint-Vincent cemetery, and I have often found myself drawn to his grave, enchanted as I am by the life and legacy of this talented but troubled genius.

Anonyme, Portrait mis en scène de Mauricia Coquiot et Suzanne Valadon, [1926], épreuve photographique, 23,8 x 18,2 cm, LEMAS 8, n° 433, Paris, Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky. Crédit Photo: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/ Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

All of this to say, while I have certainly admired Valadon from afar, it is only now, seeing her work independently of Utrillo’s, that I have started to fully appreciate her true importance. Of course, the other thing is, not only has Valadon’s work typically been viewed in the context of her son’s oeuvre but also that of her husband, André Utter, a painter himself who later became their manager. Collectively known as “the infernal trio” due to their various escapades, which you can read more about here, it meant they were often grouped together as one artistic entity.

At last, that is starting to change, however, with this major retrospective – one of the last at the museum before it closes for renovation – devoted just to Valadon. Having started out at the Pompidou-Metz, this newly enhanced adaptation features close to 200 of her works, interspersed with a few by her contemporaries. Presented across five thematic sections, they take us from Valadon’s early beginnings as an acrobat in a circus, and then as a model and muse, before her own successful career as an artist.

Although modeling provided the opportunity to learn from some of the best – including Toulouse-Lautrec, with whom she had a passionate affair, as well as Renoir – the transition between the two métiers can’t have been easy. Another of the artists she modeled for, Puvis de Chavannes, dismissed her ambitions by admonishing her: “You are a model, not an artist.” This despite the fact she had been drawing since childhood.

Suzanne VALADON, Portraits de famille, 1912, Huile sur toile, 97 × 73 cm, Don aux Musées nationaux de M. Cahen-Salvador en souvenir de Mme Fontenelle-Pomaret, 1976 Paris, musée d’Orsay, en dépôt au Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, RF 1976 22. Photo © GrandPalaisRmn (musée d’Orsay) / Christian Jean / Jean Popovitch

Luckily, she wasn’t the only one to disagree with him. One of her early champions was Degas, no less, who not only provided her with additional tuition but also bought some of her works. On discovering her talent for drawing, he proclaimed: “You are one of us!”

Increasingly regarded now as one of the most important artists of her generation, Valadon always carved her own path, eschewing the emerging movements of cubism and abstract art to pursue her own particular take on realism. Starting out by depicting family members, she later moved onto portraits of others, and eventually still lifes and landscapes, but remains most celebrated for her nudes. Historically, these had typically been painted by men, so Valadon was one of the first to bring a female perspective to the genre.

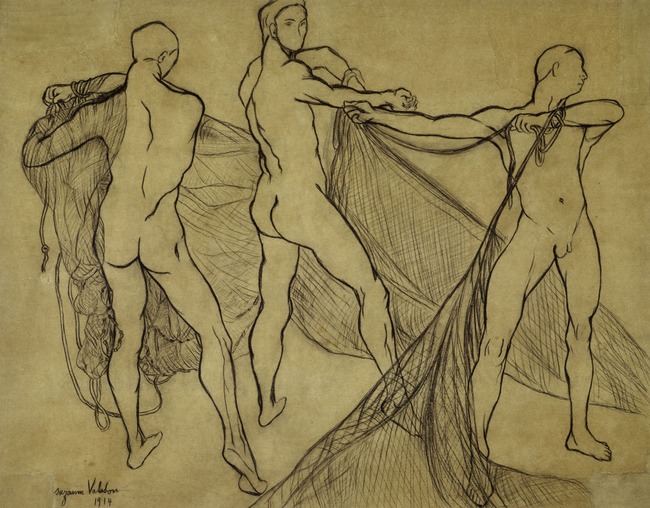

Suzanne VALADON, Etude pour le lancement du filet, 1914, Fusain sur papier calque 62 x 82 cm . Acquisition de l’Etat, 1937, Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Inv. AM 1492 D. Crédit Photo : Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/ Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

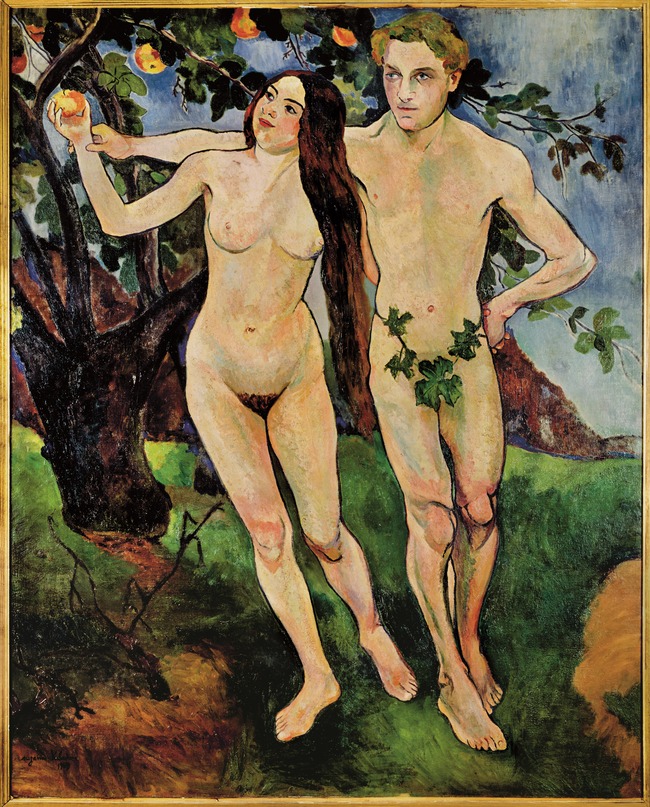

Notably, and included in this exhibition, is her depiction of Adam and Eve (1909), in which the two biblical protagonists are replaced by Valadon and her partner Utter. Both depicted stark naked in the original, this may well have been the first large-scale work by a female artist to convey full frontal male nudity – and, looking at the painting today, it seems there is a definite twinkle in Eve’s eye. Later, she protected Adam’s modesty with some vine leaves, presumably so she could get the piece exhibited, but the thought was there.

Another important masterpiece in the show is Casting the Net (1914) with its unapologetic objectification of the male body. At a time when women rarely even painted fully naked males, this painting must have been quite groundbreaking.

Suzanne VALADON, Adam et Eve, 1909. Huile sur toile, 162 × 131 cm. Achat de l’État, 1937 Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Inv. AM 2325 P. Crédit Photo: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Bertrand Prevost/ Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

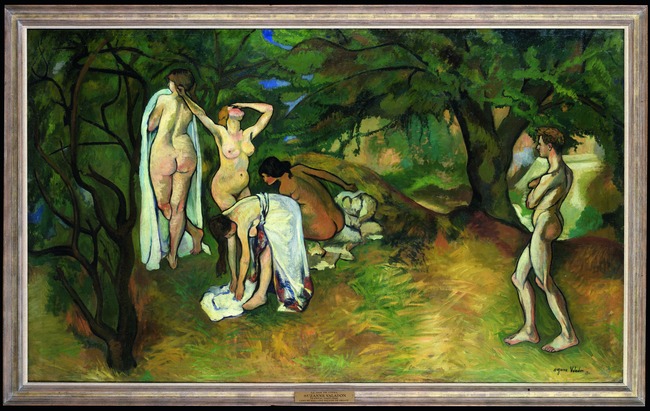

Also integral to her work, and well represented in this exhibition, are her female nudes. Often shown doing everyday tasks, such as washing, dressing or combing their hair, the subjects are portrayed just as they are – imperfections and all – rather than presented for the male gaze. There is something extremely liberating about that.

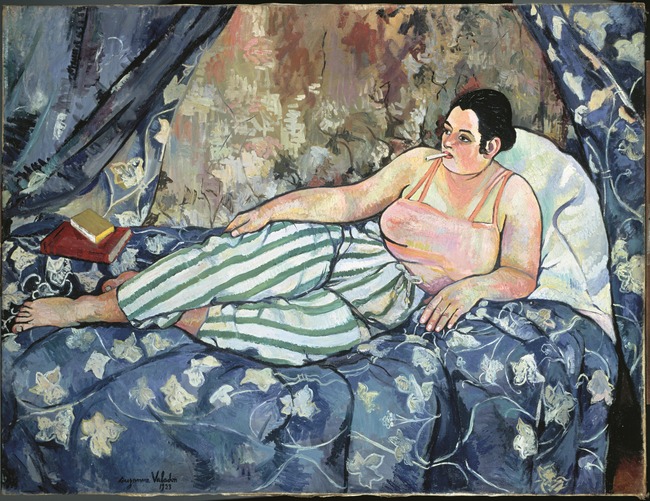

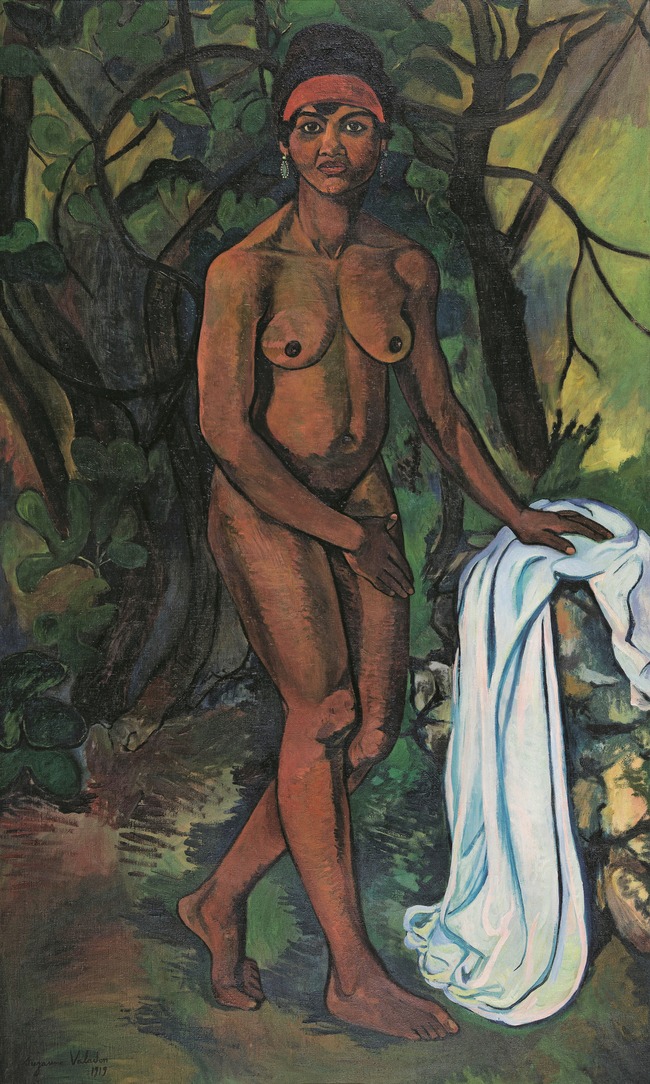

Among the other highlights in this expansive show, be sure to look out for Joy of Life (1911), where the traditional theme of women bathing outdoors is disrupted by the presence of a male onlooker; Black Venus (1919), a pioneering celebration of Black beauty; and The Blue Room (1923) where the pajama-clad, cigarette-smoking female defies the social norms of the day.

Suzanne Valadon, Joie de vivre , 1911 , Huile sur toile , 122,9 x 205,7 cm. Legs de Mademoiselle Adélaïde Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967, Metropolitan Museum of Art Inv. 67.187.113. Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image of the MMA

Seeing the works placed together in this way, and with the added context of examples by her contemporaries, Valadon’s distinctive modernist style feels bolder, more resonant and, yes, more important than ever. So, while it may be Utrillo’s work that has historically shone the brightest, with his enchanting scenes of Montmartre, it feels like Valadon is finally getting her time in the spotlight too. Long may that continue.

DETAILS

Suzanne Valadon runs at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, until Tuesday May 26.

Place Georges-Pompidou, 4th arrondissement

Metro: Rambuteau/ Hôtel de Ville/ Châtelet

Open everyday, except on Tuesdays, 11 am – 9 pm. Thursdays until 11 pm in the exhibition spaces on level 6.

Full-price ticket is €15

Suzanne VALADON, Vénus noire, 1919 , Huile sur toile, 162 × 97 cm. Donation Charles Wakefield-Mori, 1939 Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Inv. AM 3780 P, en dépôt au musée des Beaux-Arts de Menton. Crédit Photo : Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/ Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

Lead photo credit : Suzanne VALADON, La Chambre bleue, 1923, Huile sur toile, 90 × 116 cm. Don Joseph Duveen, 1926 Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, LUX.1506 P, en dépôt au musée des Beaux-Arts de Limoges. Crédit Photo: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacqueline Hyde/ Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

More in centre pompidou, Montmartre, Suzanne Valadon