See Now: Rosa Bonheur at the Musée d’Orsay

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

A curious fact about Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) is that the considerable fame she enjoyed during her lifetime faded away when she died. Her wonderful animal paintings sold for large sums in 19th-century Paris and abroad and she was the first female artist to be honored with the Légion d’Honneur. When the Empress Eugénie presented the award, her praise for Rosa’s talent was high indeed, and she also hinted that perhaps more women should be recognized in this way. “Genius,” she said, “has no sex.” Yet Rosa Bonheur was barely mentioned during the 20th century and when she began to come back into focus more recently, it was initially more as a feminist role model than for her artistic achievements.

Rosa had succeeded on her own terms, breaking many of the “rules” of the society in which she lived. She shunned marriage, earned her own living, enjoyed a long and happy lesbian relationship and dressed as she pleased, in the trousers which were practical for the artist’s studio and for the countryside which she loved to paint. It’s hardly surprising then, that in recent years she has become an example for the feminist movement. But for Rosa, her art was everything and so it’s fitting that in this year, the 200th anniversary of her birth, it is that which is the focus of our interest, most notably in the exhibition currently showing at the Musée d’Orsay.

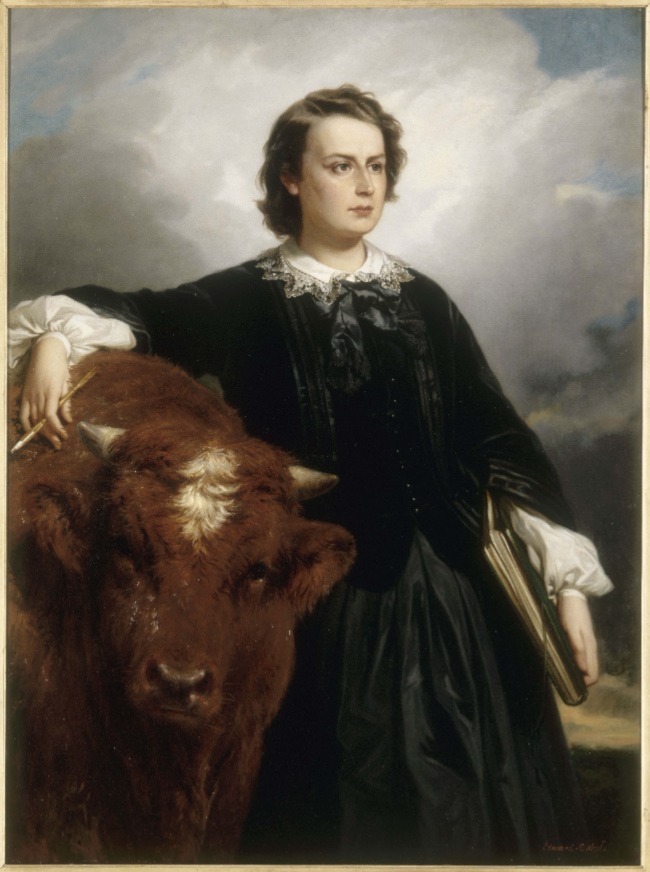

Édouard-Louis Dubufe (1819-1883) et Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Portrait de Rosa Bonheur 1857 Huile sur toile Dépôt au Musée du château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / photo Gérard Blot.

Some 200 works – paintings, drawings, sculptures and photographs – have been gathered from collections all over Europe and the U.S. and as soon as you start to look at her work, you will see her very distinctive style. Rosa spent her early years in the countryside near Bordeaux, missed it dreadfully when the family moved to Paris when she was seven, and made all things rural her subject matter as she developed as an artist. By 1860, at the height of her fame and now wealthy, she was able to buy the Château de By, a few miles from Fontainebleau, and she spent her last 40 years there, painting the animals in the forest surrounding her home and her own many pets, which included four lions!

The style in which she painted animals was revolutionary: realistic and with an extraordinary attention to detail. Without being sentimental, she captured the spirit of the animals she depicted, conveying their individuality and their feelings in a way no artist before had attempted to do. Compare the majesty of the stag in “King of the Forest” with the agony of the bird in “An Injured Eagle” or the wild beauty of the horses in “Wheat Threshing in the Camargue.” In every work, each animal’s spirit is there, firstly because it was important to her to convey their very essence as she painted and secondly because she had the technical mastery to do so.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) L’aigle blessé Vers 1870 Huile sur toile Etats-Unis, Los Angeles (CA), Los Angeles County Museum (LACMA) Digital Image (C) Museum Associates / LACMA. Licenciée par Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image LACMA

This approach was evident from the very beginning, as revealed in “Two Rabbits,” painted when she was only 19. The precise depiction of the rabbits is almost photographic and their mood seems to be conveyed too. They are huddling in a dark corner, focused on the vegetable scraps, yet also alert to the prospect of danger. The hunting dog, “Barbaro” is a beautiful creature in his prime, yet we sense his unhappiness too. Rosa Bonheur has shown him chained tightly to a wall, unable to lie down, forced to await the attentions of his owner. From his demeanor, we would not be surprised to read that he was harshly treated.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Deux lapins 1840 Huile sur toile Bordeaux, musée des Beaux-Arts Legs de François Auguste Hippolyte Peyrol, 1930 © Mairie de Bordeaux, musée des Beaux-Arts, photo F.Deval

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Barbaro après la chasse 1858 ca. Huile sur toile Etats-Unis, Philadelphia Museum of Art Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of John G. Johnson for the W. P. Wilstach Collection, 1900, W1900-1-2

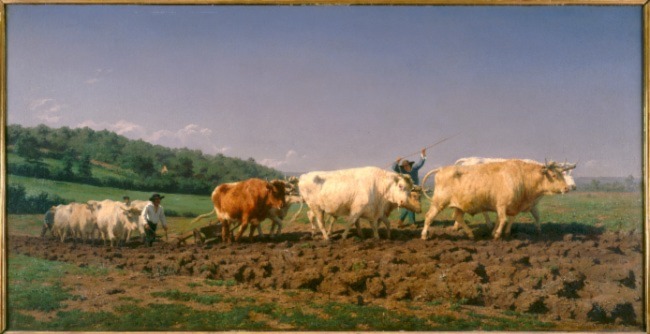

It is for her larger canvases that Rosa is best-known today. “Ploughing in the Nivernais,” showing oxen at work in the fields close to the town of Nevers in Burgundy, was painted in the artist’s late 20s and it won much praise at the Salon of 1849. It marked the beginning of her real success in the Parisian art world and was chosen 40 years later as one of the exhibits in the Universal Exhibition of 1889. It shows farmers ploughing a field, but it is their animals that catch our attention. The pairs of oxen trudge through thick clay soil, their shoulders pushed forward in exertion, and one glances out at us, so that we feel his resignation, maybe his resentment. When you look at the farmers, you see that one is waving his whip. It does not seem fanciful to say that Rosa’s sympathies were with the oxen, not with their human masters.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Labourage nivernais, dit aussi Le sombrage 1849 Huile sur toile Paris, musée d’Orsay Photo ©Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Most famous of all her works is “Marché aux Chevaux,” or “The Horse Fair.” This huge canvas – it is 5 meters long – was presented at the Salon du Louvre in 1853. It was an immediate hit with the critics and was taken on tour to England and then to the U.S., becoming the work which really made Rosa Bonheur’s name outside France. And her success was deserved, because she had been visiting local horse fairs weekly for over a year, doing hundreds of sketches of the animals and perfecting her ability to capture them in every detail. Again, the painting reveals a sympathetic connection with the animals. A jostling throng of horses is being manhandled by the dealers, and two animals in the foreground rear up rebelliously. This work is held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and, deemed too fragile to travel, is not in the exhibition, although a full-size sketch of it is on show.

Rosa Bonheur et Nathalie Micas (1824-1889) Le Marché aux chevaux 1855 Huile sur toile Londres, The National Gallery Don de Jacob Bell, 1859 Photo : © The National Gallery, London

A fascinating feature of the exhibition is the number of sketches which are on display, both painted and drawn. They are testament to Rosa’s determination to capture exactly what she saw, and they allow us to see how she built up her ideas for finished pieces. Her “Study of a White Horse, Painted from Behind” shows a deep understanding of the animal’s physiology and was surely part of her preparations for her large work, “The Horse Fair.” In “Study of a Cow” you can see not just the head of a startled cow, with a wide, staring eye, but beneath it Rosa also painted a separate, single eye, experimenting with different ways of approaching even this tiny detail. In “Seven Studies of Dogs’ Heads” she tried out the head for “Barbara” from different angles and with varying expressions. None is quite the one used in the final version, but all contribute to it.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Etude de cheval blanc de dos, n.d. Huile sur toile Barbizon, musée départemental des peintres de Barbizon, en dépôt à By-Thomery, château de Rosa Bonheur Château de Rosa Bonheur. Photo © musée d’Orsay /Alexis Brandt

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Etude de tête et d’oeil de boeuf, n.d. Huile sur toile Barbizon, musée départemental des peintres de Barbizon, en dépôt à By-Thomery, château de Rosa Bonheur Château de Rosa Bonheur. Photo © musée d’Orsay /Alexis Brandt

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) Sept études de têtes de chiens courant et un chien courant vu de dos Entre 1822 et 1899 Huile sur toile Fontainebleau, musée national du château de Fontainebleau (appartenant au musée d’Orsay) © DR

Rosa Bonheur has been the subject of much attention in recent years. So much about her resonates today. Her unwavering determination to make her own way professionally was startling to many in the 19th century, as was her quiet insistence on living her personal life exactly as she chose. Today, we recognize these traits as inspirational for their time and as a prompt for us to discover more about women artists from the past who may have been overlooked. She finds her place too in the contemporary animal rights movement and the fields of ecology and the environment. Yet, for Rosa, first and foremost was always her art. How fitting then, that this exhibition makes that its focus and does so in such enlightening detail.

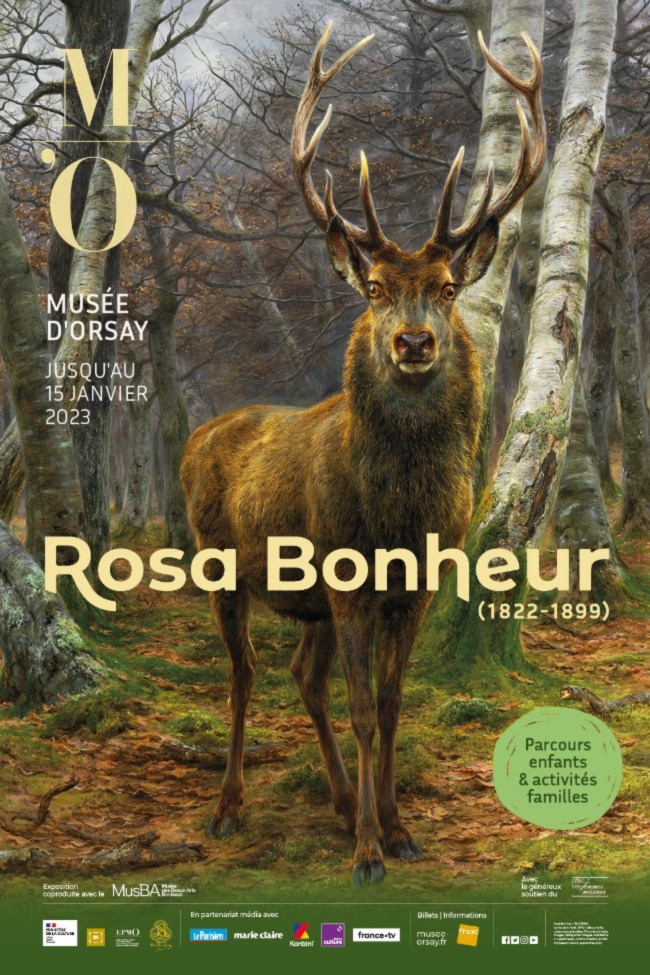

Rosa Bonheur Exhibition

At the Musée d’Orsay until January 15th, 2023.

Open every day but Monday from 9:30 a.m.- 6 p.m. (Thursdays until 9:45 p.m.)

Entry €16. Concessions €13.

Rosa Bonheur event poster, courtesy of Musée d’Orsay

Lead photo credit : George Achille-Fould (1865-1951) Rosa Bonheur dans son atelier 1893 Huile sur toile Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts © Mairie de Bordeaux, musée des Beaux-Arts, photo L. Gauthier

More in Art, artist, event, Musée d’Orsay, painting, Rosa Bonheur