Murder in the Bath: The Death of Jean-Paul Marat

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The Death of Marat, painted by Jacques-Louis David in 1793, is one of the most talked-about paintings in the Louvre, and no wonder. When you look at it, what do you see? A saint-like figure, perhaps a martyr? Or a terrifying revolutionary who, stabbed to death in his bath by an unknown young woman, has met the end he deserved? In fact, there is an argument for both answers. There is only one figure in the painting, but there are three people important to the story: Jean-Paul Marat, the victim; Charlotte Corday, his 24 year-old murderer; and the artist, who, being a close friend of Marat, interpreted events in a very particular way.

On July 12th, 1793, Jacques-Louis David visited his friend Marat at home. The two men talked politics in the room where Marat, who suffered from a serious skin complaint, often worked in his bath, attempting to soothe his pain. It was the very room portrayed in the painting. Both men were radical revolutionaries, leading members of the Jacobin faction who were responsible for La Terreur, the regime of terror which led to so many massacres and executions in Paris in the early 1790s. Neither had any idea of the fatal drama which would unfold in the same room the next day. As they talked, Charlotte Corday was preparing to travel to Paris from her Normandy home. When she arrived the next day, she bought a kitchen knife and went straight to Marat’s home, intent on murder.

Self Portrait by Jacques-Louis David, Public Domain

Turned away twice, Charlotte eventually talked her way into the house by pretending to have evidence of a plot against Marat and the Jacobins which she said was being masterminded by a rival revolutionary group, the Girondins. In fact, Charlotte was connected to the Girondins, who feared and hated the Jacobins because of their ruthlessness and cruelty. They particularly despised Marat, who as editor of a newspaper called L’Ami du Peuple, had written, “It is by violence that liberty must be established.” This made him many enemies and one, Charlotte Corday, decided to murder him.

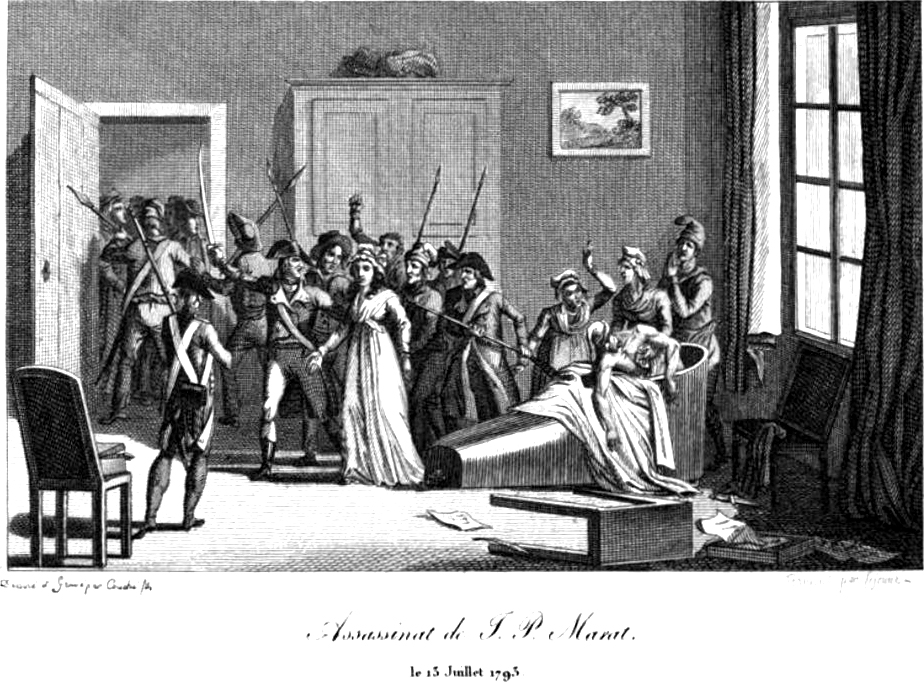

Marat’s wife showed Charlotte into the room where her husband was in his bath, having turned it into a makeshift desk by propping a piece of wood and a green baize cloth over it, just as later painted by David. Marat was very interested in the information Charlotte claimed to have and so his wife, satisfied that this was a legitimate visit, left the two alone. Almost immediately, Charlotte lunged at Marat, and drove the knife into his chest. An autopsy later revealed that the single blow had struck between his first and second ribs, reaching the heart and proving immediately fatal.

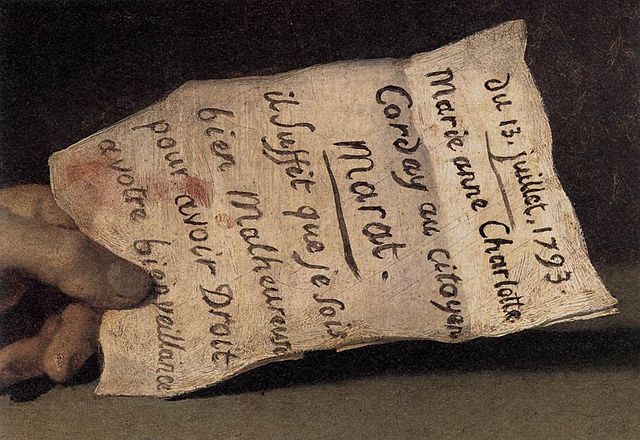

Detail of The Death of Marat showing the paper held in Marat’s left hand. Painted by Jacques-Louis David. Credit: Google Art & Culture, Public Domain

It is striking that Charlotte is not visible in the painting. She is just alluded to in the knife on the floor, and in the name at the top of the note in Marat’s hand: Charlotte Corday. The artist’s focus was on the victim, his friend and revolutionary ally, and not on the young woman who had traveled to the capital to commit what became known as “the most famous crime of the revolution.” But her resolve was absolute. She planned the murder in every detail and carried it out fearlessly. The fact that she had sewn a letter into her clothing explaining her reason tells us that she knew how dangerous her act was and accepted there was every chance that she might not survive.

Charlotte’s bravery at her trial and subsequent execution is legendary. Unrepentant, she explained that she had felt it vital to stop Marat, a key man behind the Reign of Terror, for the sake of all those he would otherwise go on to harm. “I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand,” she explained. Sentenced to death, she wrote a note to her father (“Forgive me, Papa, but the cause is beautiful”) and requested that a portrait be painted of her so that she would be remembered. A National Guard Officer, Jean-Jacques Hauer, who had been sketching her during the trial, was summoned to her cell to complete the work. It is said that she sat serenely before him, then, the following morning, she was taken by cart to the Place de Grève (now Place de l’Hotel de Ville). Dressed in the red blouson of a “traitor,” she insisted on standing the whole way to the guillotine, determined that all those who had turned out despite the pouring rain would indeed be able to see her. It was just 10 days before her 25th birthday.

The assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday. Le Jeune & Couché fils – Jacques-Antoine Dulaure. Public domain

As a close friend and ally of Marat, Jacques-Louis David painted this picture to convey certain messages. The room is accurately portrayed, but the depiction of Marat is idealized. There is no sign of the skin blemishes which disfigured his body, or indeed of the knife wound. Marat is bathed in light, almost like a saint, in a pose reminiscent of Michelangelo’s pieta. This man, the painting seems to say, was an innocent victim, a man who stood for high ideals and became a martyr for them.

But things changed quickly. Only a year after Marat Assassiné was painted, those responsible for the Terreur were overthrown. Their leader Robespierre was executed, Jacques-Louis David was imprisoned, and Marat was no longer remembered as a hero of the revolution. The painting was hidden away and not rediscovered until the 19th century, when it was put on display in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, where it still hangs today. The one in the Louvre is one of several copies produced by David’s pupils.

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique (C) Michel wal, CC BY-SA 3.0

The various fates of the three protagonists in this story are interesting. Although Marat was initially buried as a martyr in the Pantheon, his coffin was removed two years later, so tarnished had his reputation become. Much of Jacques-Louis David’s later work is familiar to art-lovers – not least because he became Napoleon’s favorite artist – but it is also true that he spent his final years in miserable exile in Brussels and was refused burial in France. Only Charlotte Corday gained respect in posterity. She lived on as the subject of other paintings and of poems, in which she was portrayed as a heroine who died for worthy ideals. By the middle of the 19th century, she had been awarded the posthumous nickname “The Angel of Assassination.”

Charlotte Corday by Paul Jacques Aimé Baudry, painted 1860. Credit: ARC Museum, Public Domain

So, what remains today of this story? Charlotte’s letter, bloodstained and bearing watery stains, still exists and is in private hands. Marat’s bath, and the knife used by Charlotte, both said to be originals, can be seen at the Musée Grévin, situated on Boulevard Montmartre, where there is a waxwork tableau of the grisly murder scene. And at the Louvre, you can see this painting, in all its contradictions: a violent scene intended to save lives, seemingly a picture of an innocent martyr, yet also of a man whom many saw as a murderous revolutionary.

Lead photo credit : Death of Marat. Painted by Jacques-Louis David. Credit: Google Art & Culture, Public Domain

More in artist, exhibition, history, painting

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY