Metro Magic: Art and Transit Merge at Louvre-Rivoli

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the third in a monthly series of stories about the wonders of the Paris Metro System.

Where can we go to feed our art- and culture-loving souls?

The museums in Paris are closed due to COVID-19 restrictions (although there is hope for reopening in the not-too-distant future).

In the meantime, we might seek out online exhibits, outdoor installations, and Zoom lectures offered by experts around the world.

One of the paths less traveled is just to linger in metro stations. A little mole-like? Too creepy? A bit seamy? Not really. There are several culturally rewarding stations in Paris.

Desperately seeking culture. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

This month’s metro focus is Louvre-Rivoli on Line 1 — the first metro station designed with a cultural theme and one of the stations worthy of spending quality time.

A mini-Louvre. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Opened in 1900, the Louvre-Rivoli station unveils a mini-Louvre (really a mini-mini-mini Louvre, since the Louvre is the largest art museum in the world).

In the short walk down the westbound quay (toward La Défense) and the eastbound quay (toward Château de Vincennes), you’ll travel the art world — from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to the cathedrals of 13th–18th century France to the struggles of the French revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Une Mère et Sa Fille (fragment from a Greek stele “The Exaltation of the Flower” (circa 470–460 BC). Photo © Meredith Mullins

You’ll meet ancient princes, scribes, and athletes, as well as goddesses, virgins, and royalty. The parade of personalities is presented in replicas of statues cast in stone, marble, alabaster, and porcelain — all in a dramatically-lit space, refreshingly free of advertising.

Metro treasures. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Most of the statues have helpful descriptions in French, English, and Chinese. Some are free from context, so you must create your own stories or just marvel at the elegance of form. Some are so famous that you don’t need a description (although you may have to activate the art history portion of your brain to identify them).

A familiar Greek goddess. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

This statue has no info plate. Can you name her? (See below for the answer.) Photo © Meredith Mullins.

The Historical Highlights

This Louvre antechamber presents several statues of Gudéa, the Prince of Lagash in Mesopotamia. The works were created around 2000 BC.

Gudea, Prince of Lagash. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

The prominent ruler Gudéa, also known as “The Chosen One,” wanted to be well remembered so he had many statues made of himself. (Several reside in the Louvre collection.) You can recognize him by his cap of tiny ornate curls and his hands often folded in prayer.

“The Chosen One,” with his cap of tiny curls. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Several Egyptian offerings provide an overview of the statues of the time.

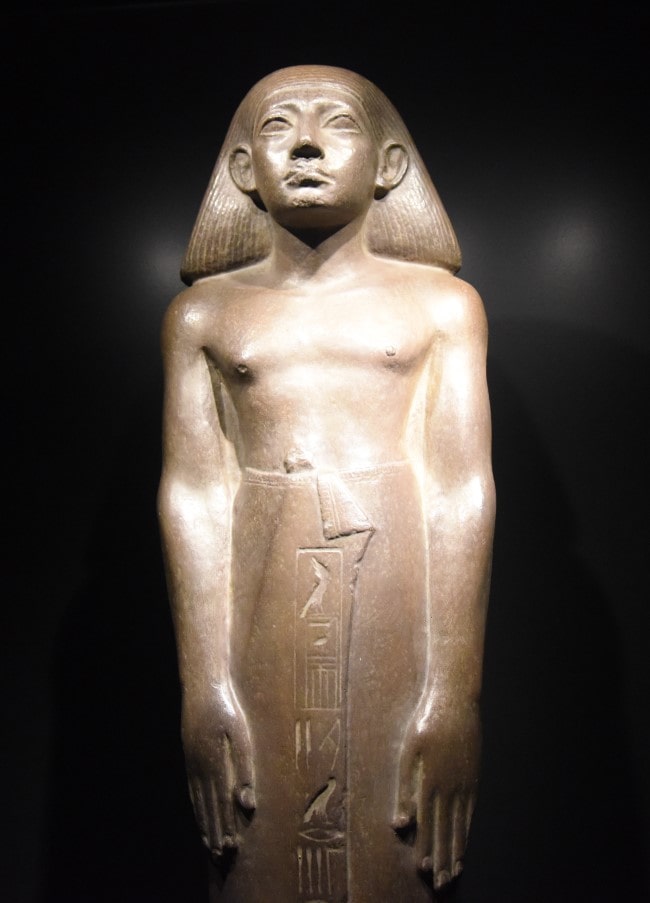

Amenemhatankh of Crocodilopolis (circa 1843–1798 BC) shows a priest/administrator holding his arms close to his body to indicate submission and devotion to his king and the gods. This position also ensures longevity for the statue (no “Venus de Milo syndrome” for him). The hieroglyphs on his long loincloth tell his story.

Amenemhatankh of Crocodilopolis. Photo © Meredith Mullins

The Goddess Nephthys (circa 1391-1353 BC) is the protector of the dead. Sister of Isis, she symbolizes darkness, invisibility, and death.

Nephthys, protector of the dead. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

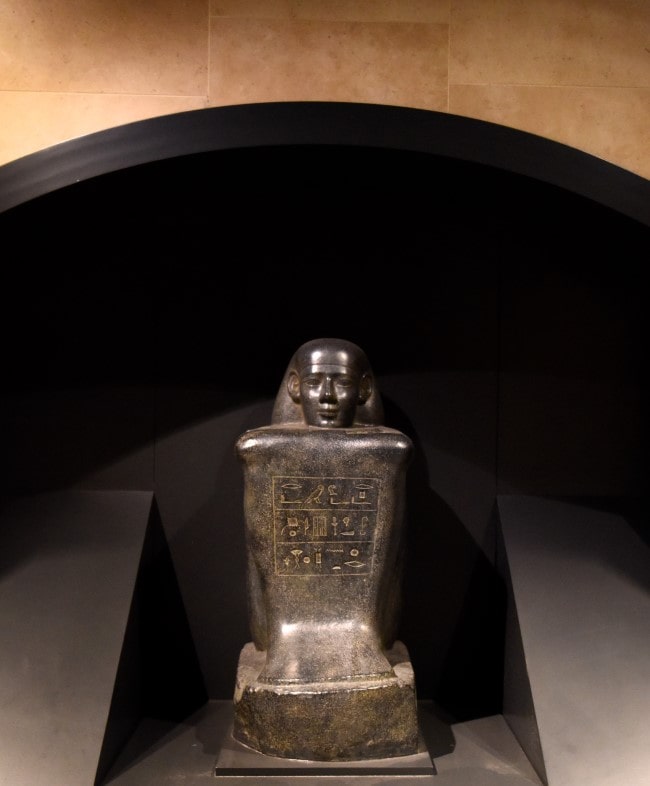

The block statue of Wahibre (circa 595–525 BC) was made to protect this wealthy dignitary while he was living, as well as in the afterlife.

A block statue of Wahibre, with hieroglyphics that identify him and his status. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

As you descend or ascend the stairs, “The Seated Scribe” (circa 2600-2350 BC) seems to follow your every move. His eyes are inlaid with rock crystal and copper.

The Seated Scribe. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Virgins are also well represented, with the “Head of a Foolish Virgin” (circa 1230) from the Cathedral of Reims and “The Virgin of the Annunciation” (circa 1335–1365), carved in alabaster and thought to be an altarpiece.

Head of a Foolish Virgin. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Virgin of the Annunciation. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

The story of Milo of Croton (statue circa 1768) is a fable hoping to deliver a life lesson. Milo was an ancient Greek athlete of legendary strength, famous for his victories at the Olympic and Pythian games. In old age, he wanted to prove his continued fitness by splitting an oak tree with his bare hands. He only partially succeeded. One hand got stuck, and he was devoured by wolves.

Milo of Croton. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Moving along in history, you’ll find a delicate porcelain bust of Marie Antoinette (circa 1774–1792) at the height of her power, with elaborate detail in the fine lace of her clothing and the gem-studded ribbon in her hair.

Marie Antoinette. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

And, in the spirit of revolution, Louvre-Rivoli presents a statue representing liberty (circa 1839), one of the key themes of France in the 18th and 19th centuries. The figure holds a rifle with bayonet, as well as papers noting key revolution dates. Lines from La Marseillaise are inscribed at the base.

Liberty. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

The Louvre-Rivoli Art Nouveau Entrance

As an added bonus, when you enter or exit at street level of the Louvre-Rivoli station, you are treated to one of Hector Guimard’s cast-iron metro entrances.

A Guimard iconic metro entrance. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Several of these entryways still exist in Paris, recognizable by the organic Art Nouveau structure, in the familiar Paris green color that resembles weathered bronze. The floral balustrades arch over the entrance with red/orange flower buds for lights, and the Japanese-influenced cartouches decorate the railings — with the elegant “M” hidden in plain sight.

The Guimard metro railing cartouche. Can you find the “M”? Photo © Meredith Mullins.

Metro Lingering

The sad news is that we often don’t do enough metro lingering to appreciate the treasures that the RATP is offering (mea culpa). The trains are usually too efficient to have time for study; and, even if there’s a delay, we’re often too annoyed by whatever is holding us up to look at anything.

Bonjour Paris hopes that you’ll now take time to stop and smell the metro roses.

A practical note: This station is not the best station to access the Louvre museum. The Palais Royal/Musée de Louvre station is closer to the current Louvre entrance.

Answer to the unidentified statue: Diana de Gabbi, a Greco/Roman representation of the goddess Artemis (circa 347 BC)

Lead photo credit : Art and Transit Merge at Louvre-Rivoli. © Meredith Mullins

More in Art, culture, Exhibitions, Metro, Metro magic, Paris

REPLY