From Paris to New York: The Life and Art of Louise Bourgeois

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“I have been to hell and back, and let me tell you, it was wonderful.”

Louise Bourgeois’s quote perfectly captures her droll insightfulness about the vicissitudes of life. She considered her artwork, which spanned most of the 20th century, the end result of a deeply personal therapeutic process that transformed her traumatic childhood experiences into a visual language. Her oeuvre is renowned for its feminine and often sexually explicit archetypal imagery, though she never considered herself a feminist. Among the most familiar sculptures are the much-exhibited “Nature Study,” a headless sphinx with powerful claws and multiple breasts, and the provocative “Fillette”, a large, detached latex phallus. Bourgeois can be seen carrying this object, nonchalantly tucked under one arm, in a portrait by the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois was born on December 25, 1911 in Paris, France. She was the second of three children born to Joséphine Fauriaux and Louis Bourgeois. Her parents owned and maintained an antique tapestry gallery and restoration workshop below their apartment in the fashionable St. Germain district. The family also had a villa in the countryside where they spent their weekends. As a young child Louise often helped in the workshop by washing, mending, sewing, drawing and recreating designs faded by wear and time. The workshop was overseen by Bourgeois’s invalid mother with whom she was very close. Her domineering father was a serial philanderer. He carried on an extended affair with her live-in nanny, who was also her English teacher. Her mother was aware of her husband’s infidelities, but found it easier to turn a blind eye.

The sexual tensions in her household simmered in young Louise’s psyche and became part of her autobiographical artistic signature. World War I also had a profound effect on her formative years. A beloved uncle died on the Western front and her father was wounded twice. One of her earliest memories was of traveling as a very small child with her mother and seeing, “…whole trains filled with wounded men with their arms and legs gone.”

Bourgeois had a broad education. As a teenager she attended the elite Lycée Fenelon in Paris. In the early 1930s she studied mathematics at the Sorbonne, a subject she valued for its stability. She found peace of mind only through, “…the study of rules nobody could change.” She also studied philosophy, writing her graduate thesis on the philosophers Blaise Pascal and Emmanuel Kant. It wasn’t until the death of her mother in 1932 that she changed directions and focused on art, first at the École des Beaux-Arts and École du Louvre, then in the independent academies of Montparnasse and Montmartre, and privately with André Lhote, Fernand Léger and Charles Despiau, former assistant to Auguste Rodin. She describes learning from Fernand Léger, the brilliant interpreter of cubism, the way to express human emotions with minimal use of line. He recognized her interest in three-dimensional form and urged her to take up sculpture. She would later explain, “I could not be a painter. The two dimensions do not satisfy me. I have to have the reality given by the third dimension.” Her father refused to support her, considering modern artists to be ne’er-do-wells. Despite this she earnestly managed to continue her education by joining classes where translators were needed for English-speaking students because translators were not charged tuition.

After several years devoted to intense study, she gained confidence in her own artistic gifts and began exhibiting her work. Around this time, she moved out of the family home into her first apartment on the rue de Seine in the same building as the Surrealist poet André Breton’s Galerie Gradiva. It was in this literary and artistic milieu she met the American art historian, Robert Goldwater, noted for his pioneering work in the field of primitive art (later becoming the first director of New York City’s Museum of Primitive Art) and the assistance he provided to many significant artists driven into exile by the Nazis, such as André Breton, Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico. Bourgeois and Goldwater married in 1938 and moved to New York City. She enrolled in the Art Students League where she continued her studies with the Abstract Expressionist Vaclav Vytlacil, befriending fellow artists who later became famous, including Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell, all of whom comprised the American Abstract Artists’ Group which she joined in 1954.

For Bourgeois the early 1940s represented the difficulties of moving to a new country, raising a family (she had three children in four years) and struggling to enter the exhibition world of New York City. Throughout the late 1940s and 50s, her husband introduced her to an influential group of New York artists, critics, and dealers, including Alfred Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art. In 1947 she had her first solo exhibition of drawings using the Surrealist technique of juxtaposing objects. Also in 1947, Bourgeois created her series of wooden and metal sculptures “Personages,” depicting totem-like structures that taper down to a delicate unstable point, appearing to lean on one another for support. According to Bourgeois they are images of friends and family, particularly her brother, whom she had left behind in France, explaining them as “a recreation of people I missed… even though the shapes are abstract they represent people. At the same time, they could also be survivors of the Holocaust emerging from the camps, or the traumatized civilians emerging from the rubble of European cities destroyed by nearly six years of war. They are not only an indictment of the war, but also the ability of humanity to resist its impact. I think they are truly noble figures.”

Bourgeois tried to defend artistic freedom under the difficult conditions of the anti-communist witch-hunts of McCarthyism. After applying for citizenship in 1950, she came under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Fortunately, her husband received a Fulbright grant, allowing the family to move to France for several years in the early 1950s, during which time her father died. Bourgeois began psychoanalysis in 1952, which she continued on and off until 1985. She was granted American citizenship in 1955. Her work at this time represented a collection of dark huddled figures greeting each other as if survivors of a terrible trauma. Bourgeois and her husband moved into a terraced house at West 20th Street in Chelsea, Manhattan, where she lived and worked for the rest of her life.

After recovering from a nervous breakdown in 1966, Bourgeois was drawn to existentialism and the freedom from the cultural straightjacket it engendered. She became part of a pioneering generation of women who broke down many barriers. Her works of this period depict the violent treatment of women. Bourgeois’s focus on both male and female genitalia was an important influence on feminist artists such as Lynda Benglis and Judy Chicago, whose works address similar subjects. The first assemblages of Louise Nevelson, for example, were produced a few years after Bourgeois had been experimenting with feminist themes. Other pieces of this period reflect her profound sympathy for the civil rights and anti-war movements. In 1970 Bourgeois participated in the campaign to defend the Judson Three, arrested and charged with exhibiting the work of anti-war artist Marc Morrell, including one notorious piece “desecrating” the US flag. Bourgeois wrote letters of appeal and donated works of art to their defense fund. “I’m afraid of power. It makes me nervous. In real life, I identify with the victim. That’s why I went into art.”

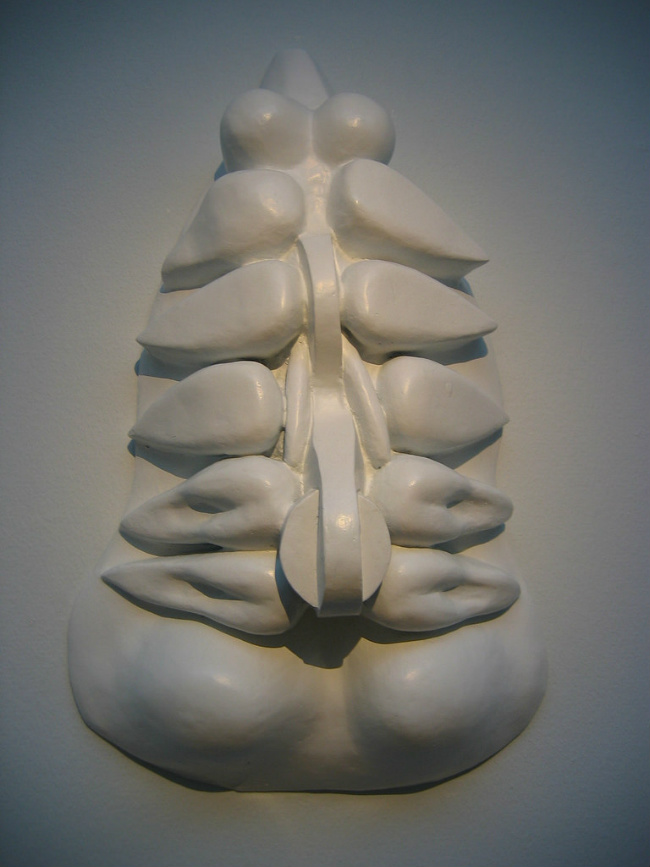

Louis Bourgeois – Torso, Self Portrait, 1963/1964. At MOMA in New York. Photo: Minke Wagenaar/ Flickr

Bourgeois’s husband died in 1973, the same year she began teaching at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn College, and Cooper Union, and the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. From 1974 until 1977, Bourgeois worked at the School of Visual Arts in New York and the public schools in Great Neck, Long Island, where she taught printmaking and sculpture.

She also became politically active as a socialist and a feminist, despite the fact that she rejected the idea that her art was feminist. Her sexually explicit sculptures show she was not afraid to use the female form in new ways. “My work deals with problems that are pre-gender. For example, jealousy is not male or female.”

With the rise of feminism, her work found a wider audience. She joined the Fight Censorship Group, a feminist anti-censorship collective founded by fellow artist Anita Steckel which defended the use of sexually explicit imagery in art. Steckel argued, “If the erect penis is not wholesome enough to go into museums, it should not be considered wholesome enough to go into women.” One of her major works from the end of this period was “Destruction of the Father.” It portrays a table in a stagily lighted recess, that holds an arrangement of breast-like bumps, phallic protuberances and other biomorphic shapes in soft-looking latex that suggest the sacrificial evisceration of a body, surrounded by big, crude mammillary forms. Bourgeois suggested the tableau’s inspiration was a fantasy from childhood in which her pompous father, whose presence deadened the dinner hour night after night, was pulled onto the table by other family members, dismembered and gobbled up. It is a disturbing work, reminiscent of the 18th century Spanish artist, Francisco Goya. Bourgeois’s most important sculptural and installation works are dominated by images of somber darkness.

In 1978 Bourgeois was commissioned by the General Services Administration to create “Facets of the Sun”, her first public sculpture. The work was installed outside of a federal building in Manchester, New Hampshire. A retrospective in 1982 at MoMA, the first given by that institution to a female artist, marked her growing prestige in the art world. Until then, she had been a peripheral figure in art whose work was more admired than acclaimed. She had another retrospective in 1989 at Documenta 9 in Kassel, Germany. In 1993 she represented the United States in the Venice Biennale. For a 1994 exhibition she created “Maman,” a sculpture of a spider, a creature she associated with her mother, an immense amalgam of soldered metal tubing, bronze, stainless steel, and marble. The sculpture is among the world’s largest, measuring over 30 ft high and over 33 ft wide. It includes a sac containing 26 marble eggs and its abdomen and thorax are made of ribbed bronze. It looms ominously over the viewer but was delicate enough to quiver and sway to the touch. It is installed outside the Guggenheim Bilbao. In 2000 a selection of her works were shown at the opening of the Tate Modern in London, followed by exhibitions at Centre Pompidou in Paris, The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte/Reina Sofia in Madrid and the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Often described as petite in size, outspoken, gruff of voice and manner, Bourgeois spent much of her time either in her home in Chelsea or in her studio in Brooklyn. In 2010 she used her art to speak up for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) equality. She created the piece “I Do” depicting two flowers growing from one stem, to benefit the nonprofit organization Freedom to Marry. Bourgeois has said, “Everyone should have the right to marry. To make a commitment to love someone forever is a beautiful thing.”

Pratt Institute in Brooklyn awarded her an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree in 1973 and Yale University awarded her the same in 1977. She was named Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French minister of culture in 1983. Other honors included the Grand Prix National de Sculpture from the French government in 1991; the National Medal of Arts, presented to her by President Bill Clinton in 1997; the first lifetime achievement award from the International Sculpture Center in Washington; and election as a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Louise Bourgeois continued to create artwork until her death, by heart failure on May 31, 2010, her last pieces being finished the week before. She was survived by two sons, Jean-Louis and Alain, two grandchildren, and a great granddaughter. Her third son, Michel, died in 1990. Her work always centered upon the reconstruction of memory, and in her 98 years, she produced an astounding body of sculptures, drawings, prints, and installations.

Lead photo credit : "Maman" by Louis Bourgeois at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Photo: Didier Descouens / Wiki commons

REPLY