James Tissot: The Painter of 19th Century Modern Life

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“Observer, philosopher, flâneur—call him what you will; but whatever words you use in trying to define this kind of artist, you will certainly be led to bestow upon him some adjective which you could not apply to the painter of the eternal, or at least more lasting things, of heroic or religious subjects. Sometimes he is a poet; more often he comes closer to the novelist or the moralist; he is the painter of the passing moment and of all the suggestions of eternity that it contains.”

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” published in Le Figaro on November 26 and November 28, 1863, translated by Jonathan Mayne in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, Da Capo Press, New York, 1986.

The poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire believed that eternal beauty could be found in the ephemeral moments of one’s own era. His well-known article “The Painter of Modern Life” was a clarion call to the artists of his day, suggesting they leave behind the classical beauty inherited from antiquity and embrace the unique beauty of their immediate environs. “Beauty is made up of an eternal, invariable element, whose quantity it is excessively difficult to determine, and of a relative, circumstantial element, which will be, if you like, whether severally or all at once, the age, its fashion, its morals, its emotions. Without this second element, which might be described as the amusing, enticing, appetizing icing on the divine cake, the first element would be beyond our powers of digestion or appreciation…” James Tissot seemed to follow Baudelaire’s exhortations to the letter by highlighting the glamorous side of the Belle Epoque. In so doing, he believed modern beauty required precision, rather softly modeled impressions.

James Tissot, The Red Jacket, 1864, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay. Public Domain: Wikipedia

At the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (June 23-September 13, 2020), the exhibition is called James Tissot: Ambiguously Modern. At the Legion of Honor in San Francisco (October 12, 2019-February 9, 2020), the exhibition was called James Tissot: Fashion and Faith. Both titles characterize the curatorial ambitions of this enormous show that tackles a most peculiar 19th-century modern artist, whose media included paint, prints, photography, and sculpture. Born Jacques Joseph Tissot, he changed his name to James Tissot in his late teens, well before he moved to England in his mid-20s. A self-conscious, somewhat contrived bicultural cosmopolitan, Tissot created a public persona at ease with himself in a rapidly changing world. This nonchalance belied an industrious soul who produced hundreds of works, sold primarily to the wealthy beau monde, whom he flattered in his lavish paintings. From start to finish, his strict Catholic upbringing remained his constant moral compass.

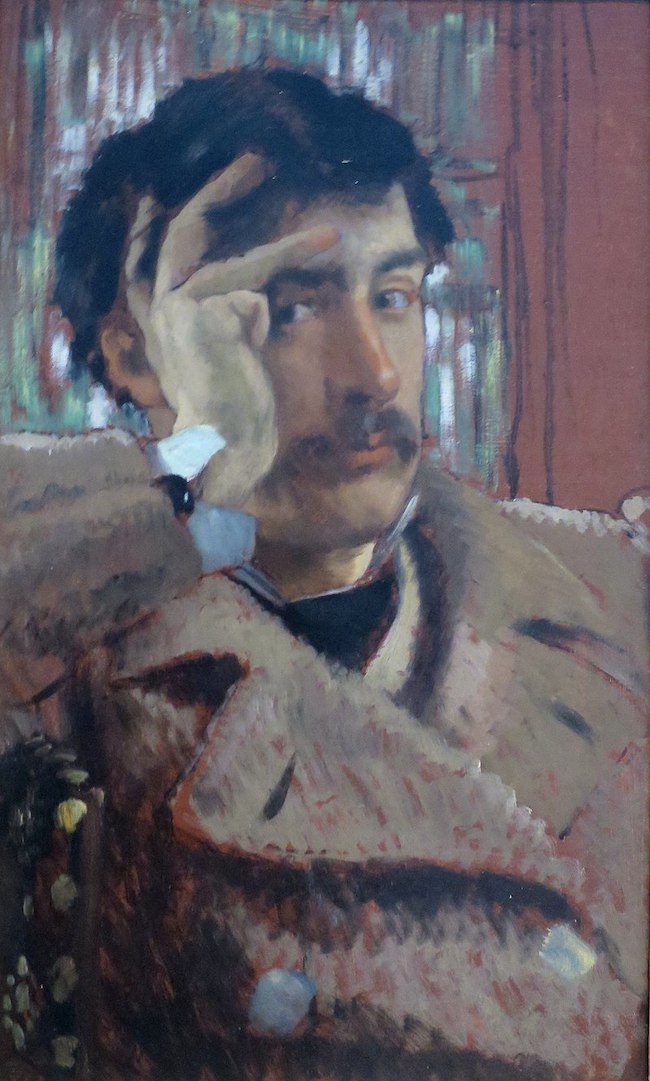

James Tissot, Self-Portrait, c. 1865, oil on panel, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Palace of the Legion of Honor. Public Domain: Wikipedia

Jacques Joseph Tissot came into the world on October 15, 1836. He was the son of a Franche-Comté cloth merchant and Breton milliner. Although much to his parents’ surprise, he chose not to enter the family business, they had only themselves to blame. In 1848, Tissot was sent to a Jesuit college in Brugelette, Belgium, where he developed his aptitude for drawing, especially the local architecture. From there he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris when he was about 20 years old. His mentors were Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres protégés Louis Lamothe and Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin, well-known for their faithful adherence to academic traditions. This taste for carefully rendered forms also dictated Tissot’s preference for early Italian Renaissance artists (such as Bellini, Mantegna and Carpaccio), the mid-19th century British Pre-Raphaelites (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones and John Everett Millais), and 16th century Germans (Hans Holbein the Younger, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Albrecht Dürer).

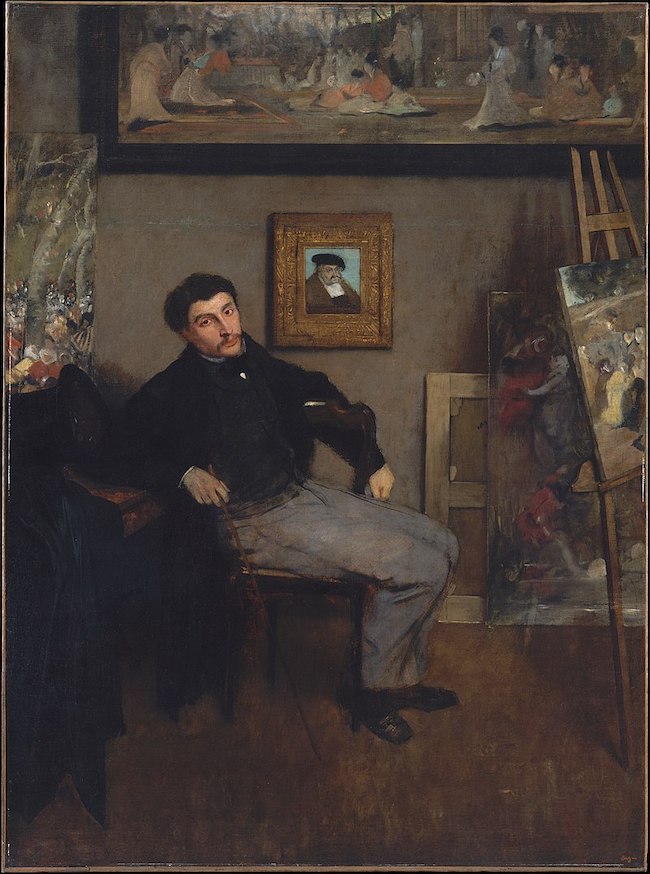

Edgar Degas, Portrait of James Tissot, c. 1867-68, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Public Domain: Wikipedia

In his portrait of James Tissot, close friend and fellow modernist Edgar Degas placed his own copy of the Louvre’s Portrait of Frederick the Wise, 1530-35 (once considered an original Cranach and now demoted to “Cranach Workshop”) right in the middle of the composition in order to underscore its significance in Tissot’s oeuvre. Just above the erstwhile Cranach, the bottom half of a large Japanese-style painting comes into view. All the rest is a clutter of canvases and studio furniture. These various influences struck the Goncourt brothers as capricious “appassionnements” that Tissot would flit through every two to three years.

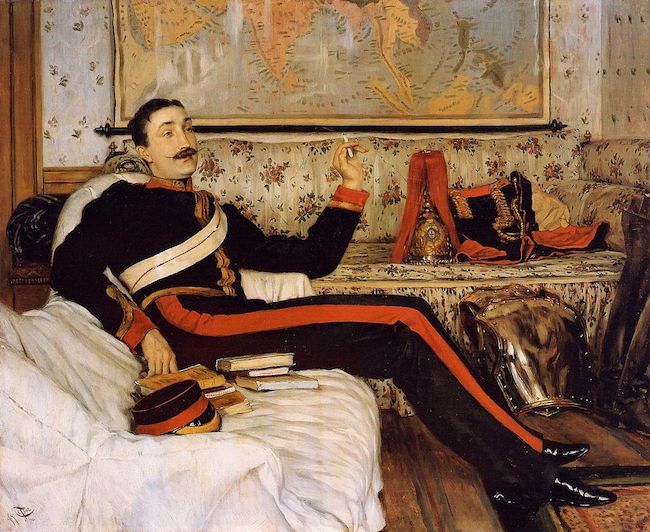

James Tissot, Portrait of Colonel Frederick Gustavius Burnaby, 1870, oil on panel, National Portrait Gallery, London. Public Domain: Wikipedia

The result may be what the Musée d’Orsay calls “ambiguous,” because we know that even his genuine chumminess with Degas, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and other experimental avant-gardists could not dissuade him from an impeccably realistic style. He chose not to participate in any of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, just like another close friend Édouard Manet. Nevertheless, he embraced all the same modern themes: picnics, shopping, public parks, and women dressed in the trendiest clothes.

James Tissot, The Gallery of the H.M.S. Calcutta (Portsmouth), c. 1876. Oil on canvas, Tate Gallery, London. Public Domain: Wikipedia

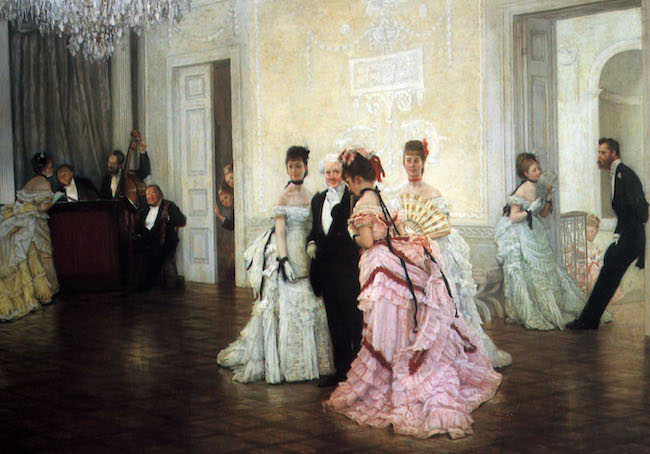

Thus, we can glean from the Musée d’Orsay’s title the need to explore our notion of “modern art,” and where James Tissot falls into this category. Modern art is about painting contemporary life. Manet and the Impressionists are credited with the invention of modern art. However, to be more precise, they are the founders of the “avant-garde,” the position that artists should invent revolutionary techniques and compositions that push artmaking toward new directions. For the Impressionists, quickly painted surfaces expressed the ephemeral nature of modern life. For the conservative Tissot, careful draftsmanship appropriately preserved modernity’s tangible experiences, especially its opulent pleasures. In this respect, Tissot’s art mirrors 19th century bourgeois materialism and nouveau riche aspirations in a manner that truly belonged to middle class values of the time. Moreover, Tissot’s vision featured the emerging modern woman: her curiosities, her dreaminess, her sartorial seductiveness, and her irresistible coquetry. These choices qualify Tissot as Baudelaire’s ideal painter of modern life, not necessarily technically innovative, but a keen observer of his contemporary milieu. In Tissot’s case, he seemed equally at home in London and Paris.

James Tissot, Seaside (Kathleen Kelly Newton), 1876, oil on canvas, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio. Public Domain: Wikipedia

Tissot stayed in Paris through the Franco-Prussian War, serving in the National Guard, up through his participation in The Commune. Following the collapse of The Commune in May 1871, Tissot moved to London, and almost immediately developed a lucrative following. He set up home and studio in St. James Woods, where a young divorcée, Kathleen Kelly Newton, lived with her first child by a lover whom she met on board ship while traveling to meet her future husband, and her sister. Newton took up with Tissot about 1875 or 1876, giving birth to a son in 1876, presumably by Tissot. Mother, children and domestic partner spent about six years blissfully residing together. The couple never married because they were both Catholic and Kathleen was a divorcée. Tragedy shattered their lives when Kathleen died of tuberculosis in November 1882. The shock was too painful for Tissot to bear alone in their London home. He quickly packed up his house, sent the children to live with Kathleen’s sister, sold his property to his friend, artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and returned to Paris within the month. He lived out his days dividing his time between his Parisian residence and the family estate Château de Buillon, near Besançon, which he inherited.

James Tissot, The Woman of Ambition (The Politician) or The Reception, from the series Women in Paris, 1885 or 1886, oil on canvas, Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Public Domain: Wikipedia

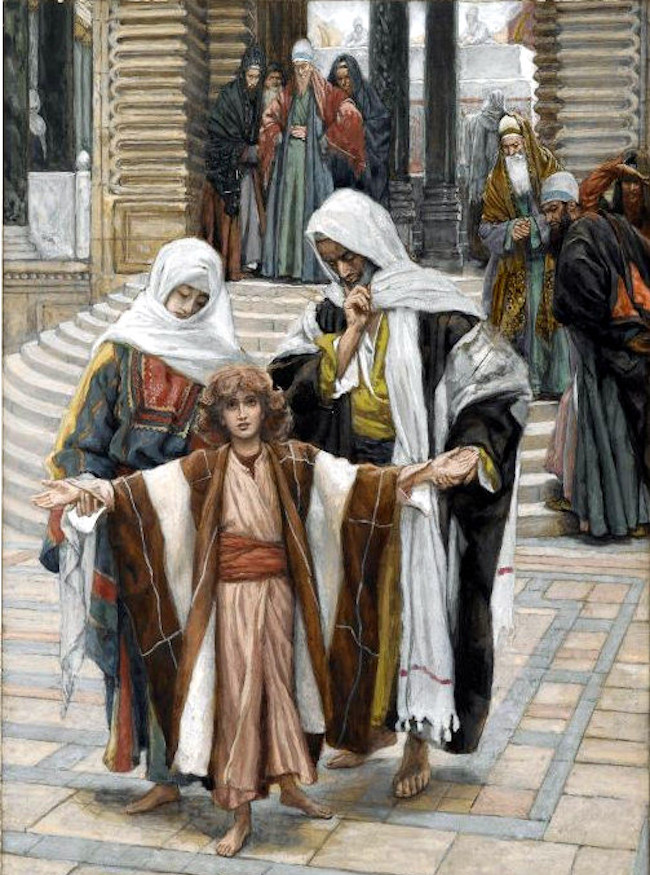

Tissot’s final three major projects were: Women in Paris (15 paintings), The Life of Christ (365 gouache drawings, executed from 1885 through 1894, now in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection) and The Old Testament (368 drawings, executed from 1896 to 1902, now in the Jewish Museum of New York’s collection). From this perspective, we can understand the American title James Tissot: Fashion and Faith, the parameters of his career, from the “beautiful people” to the Hebrew and Christian Bibles.

James Tissot, The Circle of the Rue Royale (a scene from Paris seen from the balcony of the Hôtel de Coislin overlooking the Place de la Concorde), 1868, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay. Public Domain: Wikipedia

The most entertaining aspect of Tissot’s modern art is his subtle narrative dramas, replete with social commentary. In Too Early (1873), guests awkwardly schmooze having arrived unfashionably on time. In The Circle of the Rue Royale, 1868, the sophisticated man of leisure Charles Haas steps into a group of lounging aristocrats, casually conversing with each other. A top hat, a mark of class distinction, has been thoughtlessly tossed onto the floor. Haas still wears his elegant gray hat; he has just arrived. Marcel Proust explained the trendiness of placing top hats on the floor in The Guermantes Way. Indeed, we feel the Proustian moment here, as Old World upper-crust lineage mingles with the up-and-coming parvenus. Haas (son of a German banker and naturalized French citizen) served as the model for Proust’s character Charles Swann, the rare Jew welcomed into exclusive salon circles. In Tissot’s Circle of the Rue Royale, Haas stands slightly apart from the crowd, separated by the step and his status among his Christian peers.

James Tissot, The Shop Girl, from Women of Paris, 1883-85, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of Ontario,

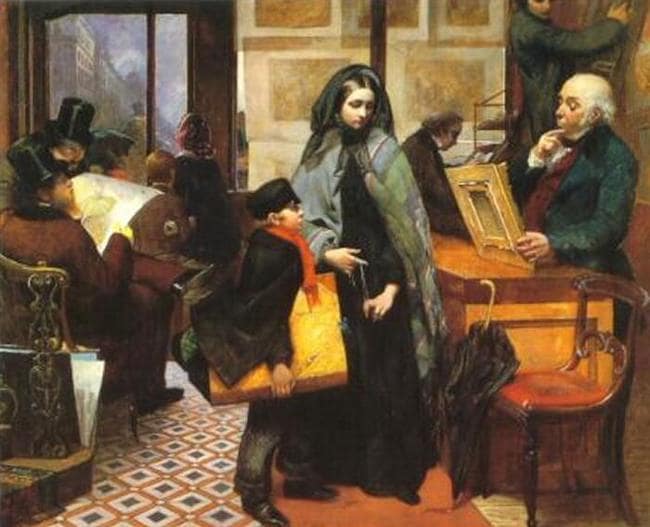

The meticulous realism of Circle of the Rue Royale begs the question: With such clarity, what could be “ambiguous” about Tissot’s modern art? To answer adequately, let’s compare The Shop Girl (1885-1886) to similar scenes by Tissot’s contemporaries Edgar Degas and the British Realist Emily Mary Osborne. All describe the confines of a contemporary store. Tissot and Osborne concentrate on specificity and narrative. Their cast of characters perform behaviors their contemporary urban audiences would most definitely understand. The architectural dimensions of each shop provide the framework for the action. Our eyes comprehend the believable space, executed in terms of Renaissance one-point perspective rules that produce the illusion of recession from foreground to background.

Emily Mary Osborne, Nameless and Friendless, 1857, oil on canvas, Tate Gallery, London. Public Domain: Wikipedia

The Impressionist Degas offers us an intuitive sense of space by tipping up the floor to indicate depth. He also obstructs our view of the central figure, intimating distance between our bodies and hers. The lighting of the scene is subdued, flattening forms and suppressing detail while emphasizing areas of reflection versus areas in shadow. Tissot, on the other hand, enlists color, more than light, to lead our eyes through his busy surface. Pink and red ribbons on the table, pink and red items in the display just beyond, a large pink ribbon on a woman’s hat seen through the shop window, a pink sign, and pink-tinted flesh on the faces of a man outside and the saleswoman inside direct our attention to the hustle and bustle of modern existence in Paris. A pink package, our package, rests in the saleswoman’s right arm. She is ready to dutifully hand it over as she ushers us out the door.

Edgar Degas, At the Millinery Shop, 1879/86, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago. Public Domain: Wikipedia/Google Art Project

Degas’ milliner may be a shopgirl, but in this painting the artist emphasizes her professional creativity. The subject is not about transactions, it’s not about sales, as we find in Tissot. Tissot’s decision to describe materialistic modern life, academically rather than experimentally, may seem “ambiguously modern” to the curators, but I think the clarity of Tissot’s work bespeaks a clear attitude toward his subject matter. For him, the modern world was about material gain and the ostentatious aspects of leisure time activities. He also injected the seamier side as well. In The Shopgirl, a pink heart-shaped ribbon lays on the floor in the foreground. This carefully placed object may allude to the shopgirls’ sales after hours, to the men who ogle them through their shop windows.

James Tissot, The Ark Passes Over the Jordan, between 1896 and 1902, gouache on board, The Jewish Museum, NY. Public Domain: Wikipedia.

Tissot fell under the spell of mysticism after the death of Kathleen Kelly Newton. He sought out séances to channel her and turned to his Catholic faith for comfort. Just as he was finishing his Women in Paris series, he had a vision of Christ in the Church of Saint-Sulpice in the 6th arrondissement. On his fiftieth birthday, October 15, 1886, he set sail for the Holy Land to prepare for his ambitious series The Life of Christ. His mission was to bring authenticity to these landscapes. Ten years later, he traveled back to Palestine to prepare for his second ambitious series, The Old Testament, anticipating 400 illustrations for the project, but only completing 200 at the time of his death on August 8, 1902. (The rest were painted by other artists who knew his work.) Best known in The Old Testament series is Tissot’s Ark of the Covenant, seen here in The Ark Passes Over the Jordan. It served as the model for George Lucas and Steven Spielberg’s epic film Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

James Tissot, Jesus Found in the Temple, between 1886 and 1894, gouache over graphite on grey wove paper, Brooklyn Museum of Art, NY. Public Domain: Wikipedia

James Tissot: Ambigously Modern was organized by Melissa Buron, director of the Art Division at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Paul Perrin and Marine Kisiel, curators of paintings at the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris; and Cyrille Sciama, director of Musée des Impressionnismes, Giverny. A catalogue in French is available through the Musée d’Orsay or online. The catalogue in English for James Tissot: Fashion and Faith is available online, while the San Francisco museums remain closed during the Covid-19 crisis. The Musée d’Orsay exhibition closes on September 13, 2020.

Lead photo credit : James Tissot, Too Early, 1873, oil on canvas, Guildhall Gallery, London. Public Domain: Wikiart.

More in 19th century, exhibition, James Tissot, Orsay Museum

REPLY