From Poubelle to Puce: The Origins of the Paris Flea Market at Clignancourt

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

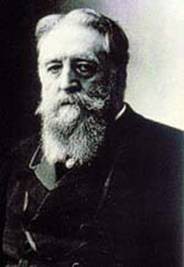

In the annals of famous French dudes, Eugène Poubelle gets a seriously bum rap. While names such as Louis Pasteur, Victor Hugo and Jacques Cousteau are well known among the Who’s Who en France crowd, poor little Eugène has been all but forgotten by the sands of time. It’s as if his name and rightful heritage have been swept under the carpet. He’s been tossed out with the poubelle, if you will. Then again, perhaps that’s fitting given that Paris might still be buried under heaping piles of rubble if it weren’t for him. Eugène Poubelle is the Poubelle of poubelle fame and trash containers wouldn’t be called poubelle in French if it weren’t for his contribution. This is the man who introduced the dust bin to Paris, and inadvertently, thanks to his efforts, les puces de Paris—the famed French flea markets—were born.

In the annals of famous French dudes, Eugène Poubelle gets a seriously bum rap. While names such as Louis Pasteur, Victor Hugo and Jacques Cousteau are well known among the Who’s Who en France crowd, poor little Eugène has been all but forgotten by the sands of time. It’s as if his name and rightful heritage have been swept under the carpet. He’s been tossed out with the poubelle, if you will. Then again, perhaps that’s fitting given that Paris might still be buried under heaping piles of rubble if it weren’t for him. Eugène Poubelle is the Poubelle of poubelle fame and trash containers wouldn’t be called poubelle in French if it weren’t for his contribution. This is the man who introduced the dust bin to Paris, and inadvertently, thanks to his efforts, les puces de Paris—the famed French flea markets—were born.

The son of a bourgeois family, Poubelle was a lawyer before becoming a diplomat, serving as the préfet of the Seine region of France. The préfecture is a prime gig in government and Eugène would have been appointed by the Sarko of his day, carefully chosen to do the government’s bidding. As a result, Poubelle held a degree of power in France made even more significant due to that fact that at that time much of the local administration at the Hotel de Ville level had been largely removed from Paris. Much like E.F. Hutton, when Poubelle spoke, people listened.

Today Paris does not have a reputation as being the cleanest city in Europe, despite employing over 2000 street sweepers and a battalion of street cleaning machines, motorcycles and trucks. But if you think the streets of Paris are a mess today, one can only imagine the stench that sprang from the city along the Seine at the turn of the century. On March 7, 1884, Eugène had had enough. “Ça suffit,” he cried, declaring that as a matter of public safety owners of buildings must henceforth provide their residents with not one but a minimum of three covered containers, each holding between 40 to 120 liters. These boxes were to contain the household rubbish from each building. A man ahead of his time, he encouraged 120 years ago what even today Parisian government officials cannot achieve. He wanted the city residents to sort their trash, dividing the refuse into perishable items, paper and cloth, crockery and shells.

The concept of a regular system with which to do away with the city’s refuse was revolutionary and the newspaper Le Monde sang Monsieur Poubelle’s praises and the people of the great city of Paris began referring to putting out their refuse bins as “putting out la poubelle.” And while the city’s residents were happy with this innovative new concept, not everyone was happy with this system. The landlords were outraged. Suddenly they were expected not only to provide the bins, but to supervise and maintain them. “Preposterous,” they cried, fearing this was a trend in the rise of tenant rights. Meanwhile, if the landlords felt they were being taken advantage of, then the “rag-and-bone men,” the chiffoniers, saw this act as a threat to their very way of living.

The chiffoniers trolled the streets of Paris, collecting rags to resell as scraps of fabric or to be rewoven or made into paper. They scrounged bones and boiled them down, creating a glob of smelly glue. It was a dirty job, but someone had to do it. If the people of Paris were sorting their own trash, how then were the Rag and Bone Men to make a living? As one might imagine, these men were not considered to be the type you’d want your daughter bringing home on a Saturday night. They were the riff-raff and by the end of the 19th century, M. Poubelle’s tidy team cleaning up the city drove them to the outskirts of town near the city gates. Of course by then the chiffoniers had began to see the benefit of the Parisians sorting their trash and instead of openly working during daylight hours they stole through the city by moonlight, picking the best of the bundles. The next day they would return to their post at the Porte de Clignancourt and the Porte de Vanves and Montreuil where they set up shop in makeshift shanty towns, selling the bric-a-brac they had found the night before.

These “moon fishermen” had an eye for style and soon these traders realized there was a benefit of grouping their wares together. Chic Parisians took notice of their quirky finds and on Sunday afternoons they began strolling to the city gates to behold the wonder of miscellaneous objects for sale just beyond the périphérique. The Parisians in their long gowns and top hats began to see these outings as a genteel sport, like fox-hunting for shoppers, seeking surprises among the brocante goods. Of course, one did have to shop carefully. While they goods for sale were intriguing, there was one flaw to the plan: often the goods for sale were infested with fleas, leading the Parisians to call an outing to the markets at the edge of town as going to “the fleas,” hence les puces de Paris.” Thanks to Monsieur Poubelle et ses amis the Marché aux Puces de Paris/St-Ouen flea market was born and today each weekend you still find flea markets at these same city gates. The rest is history. Rumor has it, the Paris Flea Market now boasts more visitors per year than the Eiffel Tower.

These “moon fishermen” had an eye for style and soon these traders realized there was a benefit of grouping their wares together. Chic Parisians took notice of their quirky finds and on Sunday afternoons they began strolling to the city gates to behold the wonder of miscellaneous objects for sale just beyond the périphérique. The Parisians in their long gowns and top hats began to see these outings as a genteel sport, like fox-hunting for shoppers, seeking surprises among the brocante goods. Of course, one did have to shop carefully. While they goods for sale were intriguing, there was one flaw to the plan: often the goods for sale were infested with fleas, leading the Parisians to call an outing to the markets at the edge of town as going to “the fleas,” hence les puces de Paris.” Thanks to Monsieur Poubelle et ses amis the Marché aux Puces de Paris/St-Ouen flea market was born and today each weekend you still find flea markets at these same city gates. The rest is history. Rumor has it, the Paris Flea Market now boasts more visitors per year than the Eiffel Tower.

As for Monsieur Poubelle, he went onto greater things. Shortly after introducing la boite poubelle, he insisted that all Parisian buildings be connected directly to the sewers (much to the chagrin of the landlords at their own expense). So successful were his efforts that his political career skyrocketed and he exalted towards higher ranks. Monsieur Poubelle became the Ambassador to the Vatican before becoming President of the Société Centrale d’Agriculture de l’Aude, where he settled safely into retirement defending the interests of bon vin et bonne vie. Of course by then “poubelle” was a household name. In the Grand Dictionnaire Universel du 19ème Siècle, the Académie française – those gatekeepers of the French language – voted to include “poubelle” as a noun, making it the official word for trash cans in France.

Want to read more about Paris flea markets?

Toma Clark Haines is The Antiques Diva™ Chief Executive Diva of The Antiques Diva & Co® European Shopping Tours offering antique shopping tours in France, England, Italy, Belgium, Holland and Germany. Please click on her name to read her professional profile and more of her stories published in BonjourParis.

BonjourParis Premium Members receive a 10% discount with The Antiques Diva™ Tours.

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters with subscriber-only content.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

Be in-the-know before you go…consult these guides to finding fabulous collectibles.

Thank you for using our link to Amazon.com…your purchases support our free site.

More in Antiques shopping, Flea markets France, Shopping