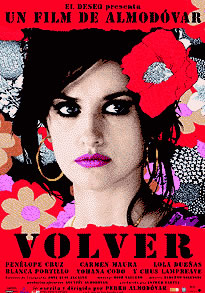

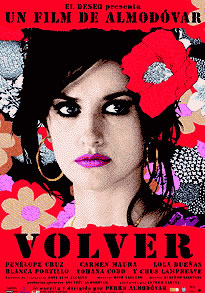

Moody Review: Volver

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It’s hard not to love the world of Almodóvar

It’s hard not to love the world of Almodóvar. All of his films (or the ones I’ve seen—which haven’t been many considering his oeuvre) are infused with an intimate knowledge of and love for his characters, one that ensures the viewer both an emotional story and a satisfying, although often painful, conclusion. Volver is no exception, but there are some vital imperfections that cause the film to fall short of some of the director’s previous works.

Quite apparent in viewing Almodóvar’s films is his innate love and unquestioning respect for women, perhaps as only a gay man can engender. The almost saintly picture he portrays of his female characters, most notably here in Volver, reminds me of how I thought of my mother when I was a child: heavenly white, incapable of the slightest harm or blemish in any way. But here is where things get a little hazy. Where are the men in this picture? They are absent, obviously and on purpose. The lines of dialogue here uttered by men can be counted on one hand, and I was left wondering: why? If the women are to be saintly and eternally victimized, but we don’t see the men let alone hear them speak for themselves, the conflict in the story suffers a strong blow.

Where are the explosive, messy portrayals of real people, not relegated to town traditions or even genders? With his previous piece, La Mala Educación, we were thrusted into a world in which the characters are hurting and hurt, guilty and innocent, male and female, and everything in between. Volver seems to be a retreat of sorts, or a zoomed-in look at a series of women spanning generations that lives under and reacts to wrongs almost entirely perpetrated by men before the film really starts. This move is interesting  as a directorial decision, since at the very beginning we are introduced to a veritable phalanx of women who are in the midst of cleaning their ‘dearly departeds’s headstones, but what Almodóvar

as a directorial decision, since at the very beginning we are introduced to a veritable phalanx of women who are in the midst of cleaning their ‘dearly departeds’s headstones, but what Almodóvar is left with afterward is a ton of exposition that at a certain point borders on soap-opera-cliché.

Perhaps this wouldn’t have been so glaring had the casting been handled differently. Penelope Cruz, a more than capable actress, is nonetheless severely out of place here, as was already apparent to me in the trailer. Quite simply, Cruz is too sexy to appear comfortable in this apron-floral-patterned tapestry of mothers and daughters. She still breathes of Hollywood on screen, and I wonder about her motivation to do this film at this point in her career. Almodóvar makes no effort to hide her bombshell-like aura, and furthermore capitalizes on her beauty and sexiness (most glaringly with an inexplicable tit shot of her washing dishes that made even me utter a noise in the salle!). Buying her as a frumpy mother trying to carry on after a difficult past is therefore difficult.

Carmen Maura, however, brings the breath of fresh air that makes this film not only enjoyable to watch, but also interesting and arresting in spite of the many elements that don’t add up. A veteran Spanish actress, Maura’s deft performance as the quasi-ghost matriarch is what allows Almodóvar to flirt with the concept of reality in his film in a new and curious way.

Perhaps the most thought-provoking element in Almodóvar’s latest is another bit of flirting: namely, his comment here on the aging process. Never before have I seen a film in which young women, vital women like Cruz’s Raimunda and her sister Sole, so willingly engage in behaviors that are almost unanimously regarded as typical to elderly European women: behaviors as delivered in the undercooked and often dreary character of Augustina, the sickly neighbor who looks to be in her thirties but behaves, inexplicably, as if she were in her eighties. Perhaps this is exactly what Almodóvar

meant to portray in his small look into a predominantly female village community; but if so, I wasn’t quite sure what he wanted to say about it.

I for one was very much in the mood to enter the world of Almodóvar, mainly because as with almost no other directors (Woody Allen, when he used to make films in New York, notwithstanding), I feel as though I am transported to his adored locales when watching his films. The immediacy and intimacy of his characters shine through here just as they do in his other films. So for that, Volver is sure not to disappoint. But for what it’s worth, make sure you’re in the mood for an international chick-flick of the highest and soppiest degree.

As a side note, make sure to catch the Almodóvar exhibition at La Cinémathèque Française in Bercy, Paris. To be reviewed soon here on BP!

Copyright © Dan Heching