Dope

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

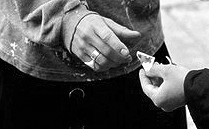

Some things need no translation, no matter where you see them. They play in a lingua franca more widespread than Greek, Latin, Pidgin, or Esperanto ever were, like the universal kabuki of a drug deal. It’s strange, now that I have to think about it, that I don’t remember ever being a bystander to a casual drug deal in Paris, and considering all the years I have been wandering the streets that people live and work in, it’s even stranger. You wouldn’t expect it on the parvis in front of Notre-Dame, but in side streets, the backwaters I have always loved and scouted? It makes me laugh. And after all these years, there’s one performed right in front of me, the buyer and the dealer furtively looking over their shoulders, their hands low, showing nothing, faithful to tradition.

A long time ago, a Frenchman sitting next to me on the plane heading home—a physician, he told me—noticed I was reading a book called L’histoire stupéfiante de la drogue and asked me what I thought. Druggingly dull, I told him, and even then it seemed the author’s golly-gee breathiness about dope in all its many, inventive forms since the Neolithic seemed enough to zone anyone out. The doctor laughed, and made a prediction.

“Drugs won’t ever catch on in France as they have in America.” Why not? “Because we drink. The French drink wine all the time. They drug themselves constantly. Why smoke marijuana and risk trouble with the cops, when you can drink all the wine you like?” Thinking of the joints I had scored two nights ago a few dingy streets east of the Sorbonne—having followed specific directions from a close friend of at least one day’s standing—I hoped the doctor was a better diagnostician than entrail-reader, but at that moment I kept my laugh to myself. Still and all, I can’t get over the missing thing—the absence of obvious drug deals in a city where, they have always told me, you can buy anything you want without running the risk of getting your brains beaten out or your roll lifted. Maybe I haven’t been paying attention.

But this is good today, and reminds me of home. The buyer, a young guy, is driving an expensive car, and the license plate tells me he’s from Neuilly. Nice suburban boy drives all the way across Paris to stop down the hill from Père Lachaise, in a street his parents would not know, to talk with a young man his parents wouldn’t want him to know—a kid from a suburb on the other side of the city, un banlieusard, and the boy is no such thing, even if he does wear his baseball cap backwards. Just like home, except I gave up dope long ago. And it turns out it shows.

The boy drives off, and the dealer sits back down at his café table with a coffee and a copy of Le Figaro—go figure that. I try and the best I can guess is that it’s not so much like home after all, where dealers tend to be lefty, at least a little, or apolitical. Is his smile, I wonder, showing his approval of Serge Dassault’s defense of stupefying bonuses for the heads of bailed-out American banks? An uptick in the sales of Dassault’s Mirage and Rafale fighters, which will keep Le Fig a going concern? I also wonder if he’s signed up for one of those learn-Wall-Street-English courses advertised in the subway and reads the Financial Times online. Some things are worth knowing—even if they do turn out to need translation or a souffleur to prompt with the true text.

I walk down the street and cross it so I can walk toward him from the front, my face as open, pleasant, and ready-to-buy as I can make it. At home, you get used to dealers, seeing a likely if unknown customer, saying “Smoke?” as you pass by. Not quite getting it the first time I heard the word, I thought the guy was trying to bum one and, as I took out my pack, he got so exasperated that he said, “No, no, I mean marijuana, you know what that is, man?” Afterwards, I was cool and just learned to say nothing and shake my head. But I must have looked likely enough, seeing how often it happened, and figure I haven’t changed much, so here goes. I’m pretty sure the French equivalent of smoke as a dope-marketing code is fumette, but I’m not positive and come away unenlightened because as I pass the dealer, he doesn’t say a word, doesn’t even look at me, even though I have slowed down and looked right at him. I cross the street and make the circuit again. Nothing.

I can’t stand it. I don’t want to smoke, but I want the offer. I backtrack, stand right in front of him, and ask, “Well, where is it?” He jumps straight out of his chair, on his feet in no time flat, and stares at me. Damn, this is not what I intended. Maybe he thinks I’m a cop or, worse, M. Prudhomme, about to lecture him on morality and reefer madness, burying him under fatuous bourgeois values or right-wing racism. It’s hard to say if he is startled or angry or frightened, but he’s not happy with me. I’ve got a few kilos and centimetres on him and a miserable history of not losing fights, but he’s carrying a lot fewer years, and I no longer carry a knife in my pocket. Blandly but not smiling, he says, “Where is what, monsieur?”

The dope, I tell him, d’la beuh. He grins, sits back down and nods at the chair opposite him. We both sit, look at one another, and this kid, it seems to me is smart. Napoleon observed that it is impossible to be tragic while sitting down—and it’s just as unlikely to be really hostile: angry people jump up from the dinner or the card table, fists at the ready, but unlike this kid, they don’t sit down again. I like him. “You want some coffee?” I tell him sure, and after the waiter brings it and goes, the young guy says, “You saw me dealing.” It’s not a question. Maybe a prelude to his story: could be good. I say yes, I did. “And?” I thought you might want to sell me some.

He says he doesn’t know me, then pauses, looking a little uncomfortable. And maybe a foreigner? “No, it’s all the same to me,” but he still looks a little off. So? “You just looked… peu probable, so I didn’t bother.” I can’t stand this either: he didn’t bother because I didn’t look like a likely customer. He’s looking very unhappy now, figuring he has somehow offended me by thinking I’m not a stoner, and he has been a bad host over the coffee he has ordered for me. “Of course,” he finally says, “I see I was wrong. Do you want a joint?”

No thanks. I don’t smoke any more, haven’t for years. If I had morphed into a giraffe on the spot, he would not have looked more surprised. He looks from side to side, his hands out from his body with the fingers spread, his eyes wide, his mouth open—the universal mime of incomprehension, also not in need of translation. He holds the pose for longer than you’d think anyone could. And to finish the ritual, he starts to laugh, not loudly, but almost painfully. Il sèche, he doesn’t get it. He doesn’t get it at all. Not to worry, kid, neither did I. Merci.

Please post your comments and let them flow. Register HERE to do so if you need a user name and password.

More in Crime in Paris, cultural differences, Neighborhood, Nightlife, Paris, Street drugs Paris