Book Review: Memoirs of Montparnasse by John Glassco

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

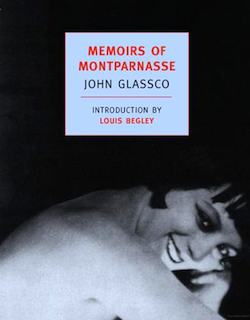

Memoirs of Montparnasse

Memoirs of Montparnasse

by John Glassco

(New York: New York Review of Books)

John Glassco’s Memoirs of Montparnasse is a pack of lies, and it doesn’t matter. Yes, he claims to know Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist and Ulysses “almost by heart” and the entire works of every writer you’ve ever heard of with the possible exceptions of Walther von der Vogelweide and Giraut de Bornelh, even though he was only twenty when (he claims) he wrote this book. Yes, he says he was in buildings in Paris that were not yet built in 1929 when he returned to Montreal. Yes, the year and a half he spent in Montparnasse was only about eight months, the rest passing on the Riviera, in Spain, and a little in Limburg—and the last month in Paris was in the hospital where they were treating him for tuberculosis. And yes, all those wonderful affairs with exciting women are a little suspect since he was certainly homosexual. So what?

I don’t believe most of The Histories of Herodotus or Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast either. But look beyond (or overlook) Glassco’s boasting and fabulation, and you will find his own idiosyncratic and charming take on expat Paris in the 1920s. He fled an overbearing father, an office job in Montreal, and buildings in which “the men and women were all busy denying their dark gods” to go to Paris, deny himself nothing, and write (what else?). “But it was more fun to play at being a writer. Later I found that a great many other young writers felt and behaved the same way. Indeed Paris is a very difficult place for anyone to work unless one is dull and serious.” So he played and was never dull or serious or even a writer.

Instead, he got the sense of the place and ultimately got it down in black and white, probably thirty years after he left, not the two or three he says in his introduction. This was undoubtedly good luck for the reader. Glassco himself admits that he no longer recognizes Buffy (his nickname in those days) as himself but as a character in a novel he may have read. And that, I think, is the point. The memoirs would not be nearly as interesting, nor would the adventures and liaisons be as engaging, had he merely kept a diary or just stuck to the truth. Like jesting Pilate, he did not stick around to hear what the truth might be.

Paris is a small city, so Buffy’s physical transitions, often several in the course of day—from bar to brothel to gay nightclub to a salon to a party to an artist’s studio—give both a sense of the time and the place as well as the frenzy of the period, the desire to be doing, to be entertained, to find the authentic which was always just down the street. And within this small city, the expatriates inhabited a kind of floating village or a ring of campfires, so it was possible to meet just about everyone as they cycled through Paris for their chance at the brass ring or just a good time. He manages to insult Gertrude Stein, to get drunk with Man Ray and Hilaire Hiler, hang out at Bricktop’s cabaret, talk literature with Morley Callaghan, and see Hemingway making an ass of himself: “I found him almost as unattractive as his short stories—those studies in tight-lipped emotionalism and volcanic sentimentality that, with their absurd plots and dialogue, give me the effect of a gutless Prometheus who has tied himself up in string.” And to top it off, he gets to know Breton, Kiki, Desnos, Joyce, and Fujita.

The name-dropping is inevitable, but his descriptions of the famous or the forgotten are fresh, like the one of Hemingway I quoted or this one: “Gertrude Stein projected a remarkable power, possibly due to the atmosphere of adulation that surrounded her: a rhomboidal woman dressed in a floor length gown apparently made of burlap, she gave the impression of absolute irrefragability; her ankles, almost concealed by the hieratic folds of her dress, were like the pillars of a temple: it was impossible to conceive of her lying down.”

He pretended to be a writer at nineteen, but he became one, and a good writer at that, years later. Anyone can observe, have adventures, eat dinner, but it takes something more—perhaps it’s the ability to make words do things you didn’t expect they could do—to make the banal observations, adventures, and dinners worth reading about. That, it seems to me, is the charm and the value of Memoirs of Montparnasse. That it is impossible to conceive of Gertrude Stein lying down tells you more than that she was fat and dumpy and imperiously temperamental. Just as it tells you more that an ex-chorus girl was “extremely pretty, with stiff frizzy hair, and an air of charming and invincible stupidity that was quite genuine” than that she was an airhead.

Writing like this is calculated, certainly, and predicated on a belief in his superiority, but that was Buffy back in the day or what Glassco wanted the old Buffy to be. And one of them (my guess is Glassco) pulls it off so well that I kept reading passages out loud. Try this one: “The oysters were so fresh they quivered when touched with the fork, the rolled and buttered wafers of brown bread were light and nutty, the bouillabaisse like a glowing eclogue.”

Buffy paid attention to what was happening to him and around him. Just as he seems to enter his dinner, he seems to inhale a truth about the French that I have never heard or read before: “…one discovers the French people are not, as is generally believed, exclusively interested in money, and that their real passion, as an essentially feminine people, is to confer favours, indulge their egoism and feeling of superiority to the rest of the world by acts of condescension and grace.” He also learned to pay attention to the ordinary, avoiding the Louvre, the Champs Élysées, and Les Invalides (he sees it as he comes out of the subway and flees back downstairs) for homely streets like Alésia and Gaîté, which may be why my friend Joseph Lestrange recommended Memoirs of Montparnasse to me and yet another reason for me to recommend it to you.

The book has an intelligent and wry introduction by Louis Begley, brief biographies of the men and women who populate Buffy’s time in Paris, including the real names of those to whom he gave pseudonyms, an explanatory list of some of the famous places Buffy and his friends frequented. They are not necessary, but helpful as are the photographs, though some of the people who seemed glamourous in Glassco’s writing seem rather ordinary and dumpy in black and white.

Why shouldn’t they? They were to Buffy what he, or Glassco, wanted them to be. And we are warned. He writes that his father’s insistence on the truth “made me an accomplished liar at an early age; the constant need for lying had sharpened my invention and contributed enormously to my enjoyment of the highest forms of poetry” and also evidently of day-to-day life. Keep that in mind as you read and enjoy this book.

© Thierry Picot

Thierry Picot is a franco-américain who took early retirement from academia, where he taught medieval history and Romance linguistics. Please click on his name to view his profile and other stories published in BonjourParis.

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters with subscriber-only content.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

Update your library…click on an image for details.

Thank you for using our link to Amazon.com…we appreciate your support of our site.