André-Jacques Garnerin: The Parachutist of Parc Monceau

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

André-Jacques Garnerin’s ascent to becoming the world’s first parachutist was harder than his descent—although his landing had a few bumps. Born in 1769, the Parisian daredevil survived the French army and spent three years as a prisoner of war in Buda, Hungary until 1797 before making the leap to parachuting; these experiences awakened his desire to pursue the possibility of human flight.

As the inventor of the frameless parachute, it seemed appropriate that Garnerin would also be one of its pioneers. He had always had a fascination with ballooning and even recommended the use of the balloon for military purposes. Garnerin’s parachute resembled an umbrella with 36 ribs and lines. The “umbrella pole” ran down the centre of a man-sized basket and had a rope connecting it to the balloon.

The first time the French aeronaut attempted his parachuting endeavour, the hot-air balloon was unable to achieve lift-off and riots ensued; the second time around, Parisians were skeptical, but no less enthralled with the idea. (Indeed, Parisians have always enjoyed having any excuse to look skyward.)

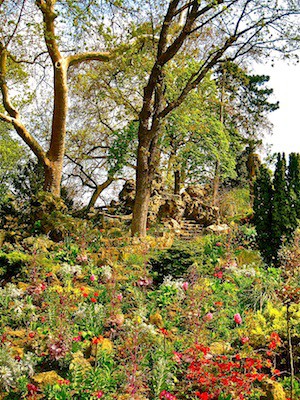

Garnerin chose Parc Monceau in the 8ème arrondissement to be his landing spot. It was the perfect venue for the king of parachutists: the park was built for royalty by the whimsical designer and architect Louis Carrogis Carmontelle. It was one of the earliest examples of an English-style landscape garden and was renowned for Les Folies des Chartres, an amalgam of architectural follies that included an Egyptian pyramid and a Dutch windmill. This garden of dreams would become the place where Garnerin could realize his own.

Garnerin chose Parc Monceau in the 8ème arrondissement to be his landing spot. It was the perfect venue for the king of parachutists: the park was built for royalty by the whimsical designer and architect Louis Carrogis Carmontelle. It was one of the earliest examples of an English-style landscape garden and was renowned for Les Folies des Chartres, an amalgam of architectural follies that included an Egyptian pyramid and a Dutch windmill. This garden of dreams would become the place where Garnerin could realize his own.

On October 22, 1797, the sky was enlivened by a sky-warrior uneasily floating upwards. A hush fell over the expectant crowd as Garnerin’s hot-air balloon rose above the silvery, bright trees of Parc Monceau and gradually replaced the dying sun.

Garnerin reached a height of 900 metres (3000 feet) in his hydrogen balloon and then started to cut the rope connecting his parachute to the balloon. Garnerin later recalled the enormity of this moment: “I was on the point of cutting the cord that suspended me between heaven and earth and measured with my eye the vast space that separated me from the rest of the human race.”

The balloon continued upward while Garnerin descended with the silk parachute blooming like a single cloud above him. Then he started to gain velocity and the basket began to lurch on oceans of air.

It is alleged that Garnerin suffered from motion sickness and vomited on the exultant crowd below. He reportedly said that he “usually experienced painful vomiting for several hours after a descent.” (In 1804, French scientist Joseph Lelandes introduced a vent in the center of the canopy that eliminated these violent oscillations.) The basket plummeted to the earth like a meteor, bumping and scraping its way to a standstill, but Garnerin emerged unscathed. He promptly mounted a horse and trotted through his admirers and into the history books.

It is alleged that Garnerin suffered from motion sickness and vomited on the exultant crowd below. He reportedly said that he “usually experienced painful vomiting for several hours after a descent.” (In 1804, French scientist Joseph Lelandes introduced a vent in the center of the canopy that eliminated these violent oscillations.) The basket plummeted to the earth like a meteor, bumping and scraping its way to a standstill, but Garnerin emerged unscathed. He promptly mounted a horse and trotted through his admirers and into the history books.

Parachuting became something of a family hobby for Garnerin: two years later, his future wife Jeanne Geneviève Labrosse became the first female parachutist. In 1815 Garnerin’s niece Élise began a career as a parachutist and went on to perform 39 parachute jumps. In 1823, Garnerin was killed after being struck by a beam while working on his balloon equipment. He was only 54 years old.

It has been argued that one of Garnerin’s contemporaries actually deserves the title of first parachutist: Louis-Sébastien Lenormand, the professor who had named the parachute. He made a parachute jump from the tower of the Montpellier observatory in front of a smaller crowd that included Joseph Montgolfier, one of the inventors of the hot-air balloon. However, Garnerin is the first person to make a parachute jump from high altitude and had hundreds of witnesses to prove it.

Garnerin was more of a gravity performer than a scientist. Perhaps this is what enabled him to tap into the public’s fascination with flying. More importantly, he proved that the air between heaven and earth was navigable.

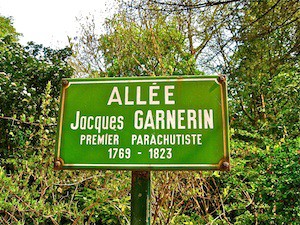

Today, the memory of Garnerin is very much alive in Parc Monceau: there is a plaque on his historic landing spot and an allée named after him. During the day, the park is overrun with school children indulging in flights of fancy. It is possible there are a few parachutists among them—although the frontiers may have changed, the world’s appetite for falling remains undiminished.

More in French history, Neighborhood, Paris history, Paris parks