Contralto

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

I have no idea why I’m here, but I am pretty sure I shouldn’t be. I guess I should correct that. I’m here because I walked in the front door of my own free will, and there’s nothing remarkable about why I came in. I didn’t feel like having dinner two hours ago, it’s late, I’m slightly lost and now I’m hungry. The café, a new one to me, was here, so here is as good as there, I figure, and here I am. The menu looks promising enough, I order, and start looking around for the first time.

I have no idea why I’m here, but I am pretty sure I shouldn’t be. I guess I should correct that. I’m here because I walked in the front door of my own free will, and there’s nothing remarkable about why I came in. I didn’t feel like having dinner two hours ago, it’s late, I’m slightly lost and now I’m hungry. The café, a new one to me, was here, so here is as good as there, I figure, and here I am. The menu looks promising enough, I order, and start looking around for the first time.

And that’s when I think I shouldn’t be here. Across from my table, on the right-hand side of the café, against the wall there’s a small raised podium with an upright piano off to one side and a mic stand front and center. I have a feeling they’re about to be used. The waiter arrives with my Cynar, ice on the side, and let’s me know I’m right. Mademoiselle Une Telle, I can’t quite catch the name, is a jazz singer, just back from a concert tour, very popular… Where? He doesn’t know, but it was somewhere “in the north where she’s from, I think.” Finland and Estonia? He shrugs. It doesn’t matter. I want to eat and maybe read a little before going home and to bed. I don’t want to be sung to. Not here, not now, not jazz.

You’re supposed to say (aren’t you?) that jazz, like Baroque music and hip-hop, is international, you’re supposed to believe (you do, don’t you?) that music is not geography or even culture, just the instruments and talent, neither of which has ever needed a passport and a security clearance. You’re supposed to. Maybe I am too, but I don’t, at least not without misgivings, which you may call (feel free) nothing more or less than parochial prejudice, musical jingoism, but I’m the one here, prejudice and all, and about to hear, reluctantly, a woman from the frozen north sing jazz in Paris—her recent triumph in the Baltic or among the Inuit notwithstanding.

And, the waiter tips me, she’s a contralto. Right. They say that a contralto can be the sexiest woman’s voice because even sopranos drop into the lower register when they are sexually aroused and so the voice makes men, and no doubt some women too, feel like lovers at the charismatic moment: just hear Marlene Dietrich crooning to the world that, from head to foot, she’s made for love, if you doubt me. Beyond that, the contralto is often purely a wonderful voice. Think of sassy Sarah Vaughan or Ella who, with her three octaves, often meandered and enchanted in the garden enclosed by F below middle C all the way up to the second G above it.

But too many wind up sounding mannish or they growl or have to fake the bottom of the range and sound like a foghorn or a noise coming through the door of the WC. Risky business, being a contralto. Ditto, listening to one. But the lady in question, her accompanist trailing in her wake, is coming out, so here goes. Might as well relax and enjoy it. To be on the safe side, I ask the waiter to leave my bill when he brings me my late dinner. Showtime.

A few people clap, but most are still eating and talking which, for the French, is a single enterprise. But she does something that gets my attention. She nods at her piano-player who picks up the mic stand and moves it out of the way. Good, good so far, she’s not going to blast us. It’s a bit late, but I clap a couple of times anyway and earn a smile.

A few people clap, but most are still eating and talking which, for the French, is a single enterprise. But she does something that gets my attention. She nods at her piano-player who picks up the mic stand and moves it out of the way. Good, good so far, she’s not going to blast us. It’s a bit late, but I clap a couple of times anyway and earn a smile.

She begins after another nod to the accompanist without naming her tunes. The music is unfamiliar and not interesting, the pianist has too much left hand, but her voice is like honey, with something else in it, a little lemon or vinegar to thin it a touch and give it an edge, to make it savory, not merely thick and sweet. Better than my meal which I’m having a hard time remembering to eat. She’s not fighting against the mediocre music or the weak accompanist. She is simply ignoring them and making something out of practically nothing at all.

And it gets better. She starts rifling the American songbook—torchy evergreens like “One for my Baby,” “Miss Otis Regrets,” and “I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance,” and upbeat flings like “Oh, Look at Me Now” and “Pick Yourself Up”—and, damn, has she ever got my attention. Singing always improves an accent in a foreign language. Still, her English is weak, but she understands the lyrics even if she can barely get her mouth around the foreign phonemes, and she feels what’s she’s singing. She cops the hurt and the humor, she delivers them without gift wrap, she is singing from the soles of her feet and the bottom of her soul—with phrasing as murderously seductive as Lady Day’s or Lee Wiley’s. I could wake up and fall asleep and spend all the time in between going to bed and getting up listening to that voice and all it conveys.

And then she stops, and everything in me says, No, don’t, even though she has been singing for at least forty-five minutes without patter or pointless bridges with finger snapping to rest her voice. But she’s not leaving the little stage in this slightly forlorn café. She’s talking earnestly with her piano man who listens, responds, seems to disagree, then takes an envelope from the top of the piano and pulls out some sheet music. She walks back to the front of the podium, smiles, and says only Claude Bolling. Oh. I don’t know a lot of his music, but he was a formidable pianist who also wrote jazz suites—something that often makes me mistrustful—and has written for and played with Rampal and Yo-Yo: the kind of musician who can make the case that jazz may be the successor of Debussy and Stravinsky. But—what do I know? probably nothing—for the life of me I can’t think of any songs he wrote, lyrics, words, the meaningful things beyond program music and emotional blackmail. So, Joe, wait and see…

…and hear, and I do. No, she hasn’t written lyrics for Bolling. She’s doing vocalise—not scat and not solfège, but simply pure sound, or vowels if you want to take the musicologists’ word for it—musical voice without dictionary meaning, but meaning. No, it’s not new— Fauré, Rachmaninoff and Villa-Lobos used it, and so did Manhattan Transfer and famously Yma Sumac—so maybe the case for jazz as part of the great tradition going back to Gesualdo and even plain chant and going forward to what I am hearing now is stronger than I may have thought. I do not remember everything she sang, non-stop, for another thirty minutes, but I do remember her vocalising Bolling’s Sentimentale, a song you may have heard, even if the name is unknown to you.

She finishes her last vocalise number with a poignant counterpoint. Bordel de merde!… that tells me she’s done for the night and, sure enough, she bows, hears the little applause from the dozen or so of us left here, and walks off. I can’t bear it. I want more and despite my famous shyness, walk towards the back of the café where she has gone. Another waiter standing there asks me what I want. To meet madame, I tell him. Oh, I don’t think so. They tell me she is very shy, but I don’t know. She’s probably gone home. Swell, even if I met her, we could spend three years staring at our shoes even if I caught her before she left.

She finishes her last vocalise number with a poignant counterpoint. Bordel de merde!… that tells me she’s done for the night and, sure enough, she bows, hears the little applause from the dozen or so of us left here, and walks off. I can’t bear it. I want more and despite my famous shyness, walk towards the back of the café where she has gone. Another waiter standing there asks me what I want. To meet madame, I tell him. Oh, I don’t think so. They tell me she is very shy, but I don’t know. She’s probably gone home. Swell, even if I met her, we could spend three years staring at our shoes even if I caught her before she left.

Do you know her name? Will she sing here again? She is called Suzanne, something like that, she sang last night and tonight, and that’s it. Fini. A CD, anything? Information, biography? No, monsieur not even une affiche in the window. But she has been touring? Don’t know, don’t think so. I think she is a friend of the owner, you know? He rented the piano three days ago and the microphone, but she didn’t want it, the micro. But she’s not coming back, she’s leaving, that’s what the boss told me. So, how do I find her, how can I hear her sing again, where? Aucune idée, monsieur. This is the first time we have had a singer here, ever. And, pardon, monsieur, but it’s getting late, no one else is here and I would like to cash out and close up.

photo 1: Sarah Vaughan, 1946 by William P. Gottlieb [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

photo 2: Marlene Dietrich by George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

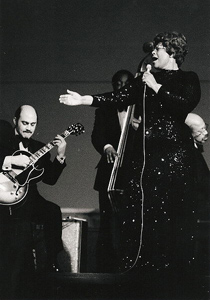

photo 3: Ella Fitzgerald and Joe Pass in concert, 1974 by Hans Bernhard [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

More in Cafe, french life, Paris cafes