A Multitude of M’s at the Musée d’Art Moderne: Matisse, Marguerite, and Münter

At first glance, the many M’s currently at the Musée d’Art Moderne may seem a surprising combination of artistic visions. As you spend time in these two remarkable exhibits, you discover that pairing Matisse’s homage to his daughter Marguerite with the first French retrospective of German Gabriele Münter is, in fact, curatorial genius.

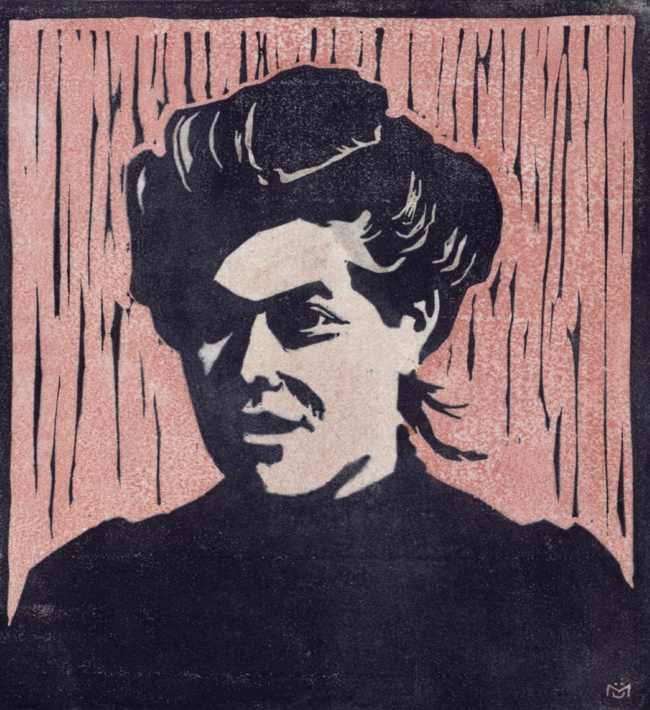

“Self-portrait.” 1909-1910. Gabriele Münter. Oil on cardboard. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

In many ways, these linked exhibits follow the museum’s focus on the influence of women in the art world, especially in France — as artists, subjects, and inspiration. (Note past exhibits such as Sonia Delaunay in 2014-1015, Paula Modersohn-Becker in 2016, and Anna-Eva Bergman in 2023).

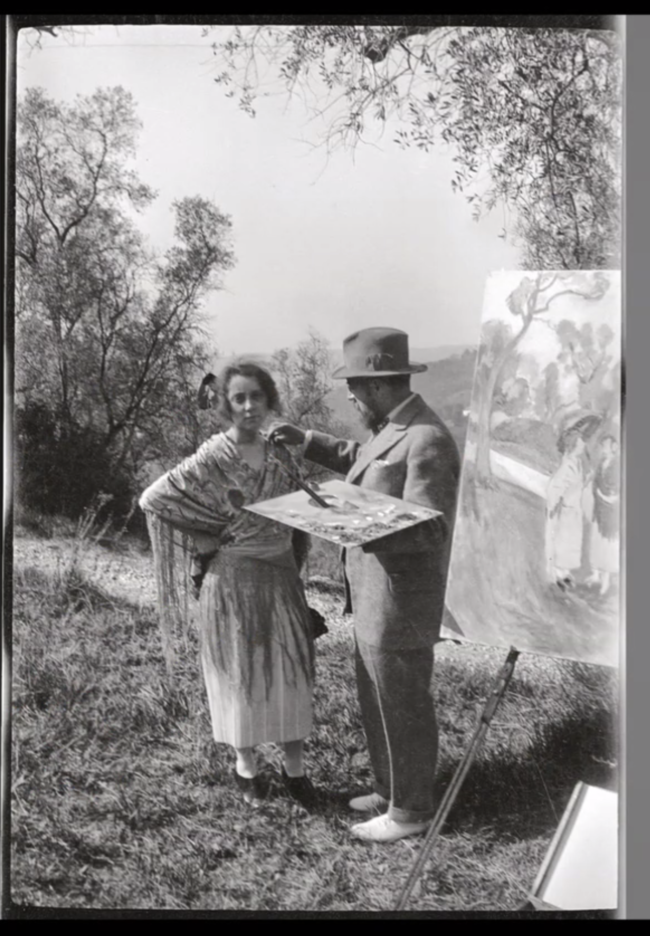

“Through Her Father’s Eyes”—An artistic bond . . . for life. “Conversation under the Olive Trees (Marguerite and Henri Matisse).” 1921. Henriette Darricarrère. Credit: Archives Henri Matisse.

Matisse (1869–1954) and Marguerite (1894–1982)

The Matisse exhibit (“Through Her Father’s Eyes”) features paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, and ceramics of his eldest daughter Marguerite, reflecting a father’s protective and tender relationship with his child — one who was a reassuring presence in his life.

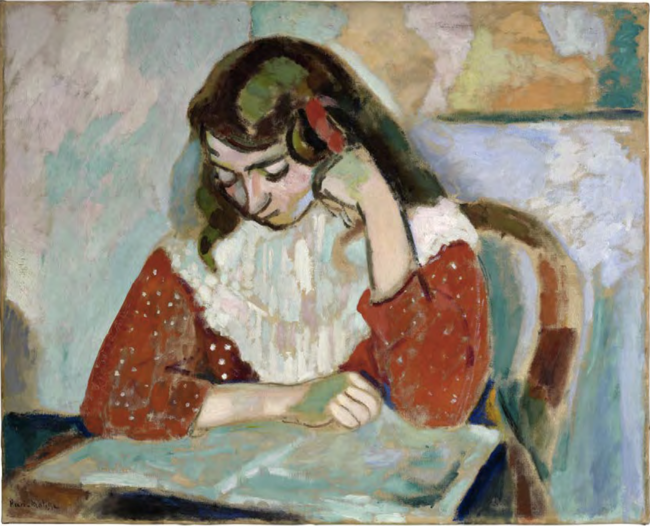

“Marguerite Reading,” 1906. Henri Matisse. Oil on canvas. Credit” Musée de Grenoble.

Because of Marguerite’s fragile health and need to often stay home from school, she was a constant fixture in the studio, living with what she would later describe as “the daily drama of his painting.”

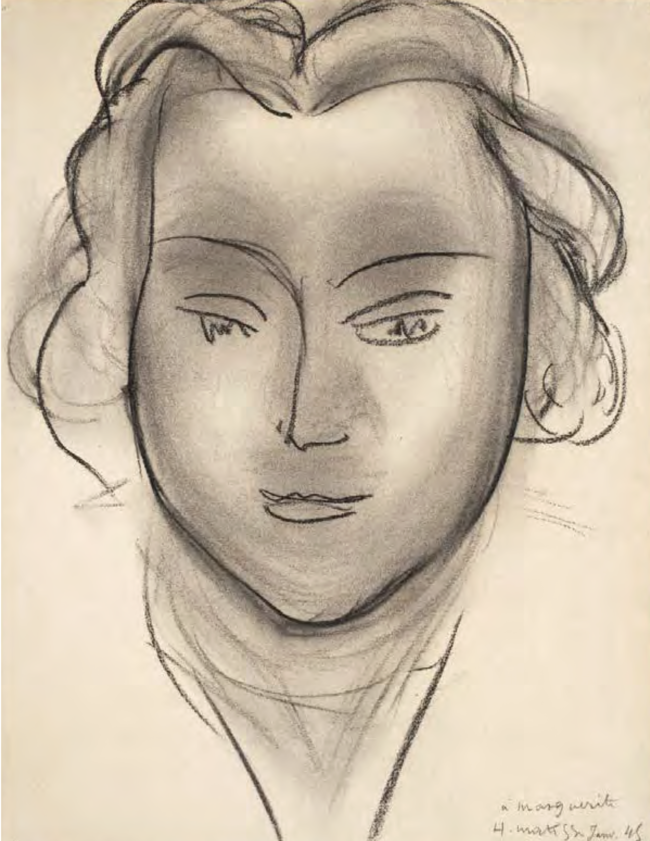

Through Matisse’s eyes, we are able to follow Marguerite from child to young woman to married adult with artistic passions of her own to her role as activist in the French resistance during the Second World War.

“The Music Lesson.” 1921. Henri Matisse. Oil on canvas. Photo Credit: Meredith Mullins

Marguerite’s mother was Caroline Joblaud, one of Matisse’s models. After the couple separated, Matisse officially recognized Marguerite as his daughter. A year later, he married Amélie Parayre, who agreed to raise Marguerite as her own child.

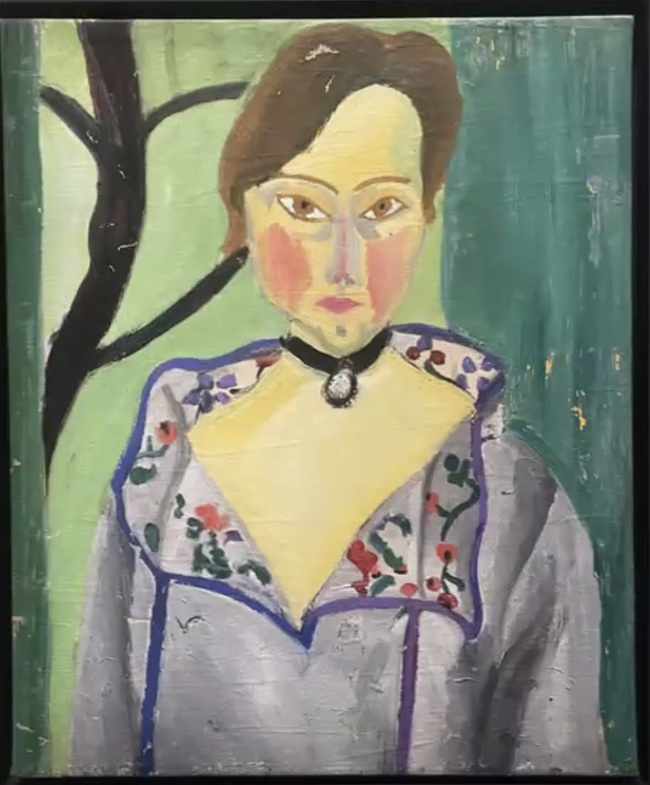

After early illnesses, including diphtheria, Marguerite required a tracheotomy when she was seven, leaving a hole-like scar that she covered with a black ribbon or high collared blouses — always distinctive in Matisse’s paintings of her.

A painting that Picasso loved (and acquired). “Marguerite.” 1907. Henri Matisse. Credit: Grand Palais/René-Gabriel Ojeda.

One of the more tender paintings shows Marguerite after her final tracheotomy surgery in 1920 — exhausted, but finally freed from the stigma of the visible scar.

“Marguerite Sleeping.” Etretat 1920. Henri Matisse. Oil on canvas. Private Collection/ © Martin Parsekian.

The exhibit of more than 110 works has been chosen from French, American, Swiss, and Japanese collections, many works shown in France for the first time. The exhibit also includes work from private collections, rarely, if ever, shown to the public.

“The Moorish Screen.” 1921. Henri Matisse. Oil on canvas. Credit: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

You might think that so many images about one person would be annoyingly repetitive. But the exhibit is fascinating for the very depth of the exploration. Matisse captures many facets of his daughter’s personality and growth. As the museum mentions in its introduction, he “seemed to see in her a kind of mirror of himself.”

“Marguerite with Black Cat.” 1910. Henri Matisse. © Centre Pompidou/Georges Meguerditchian

In parallel with Marguerite’s evolution, we follow Matisse’s evolving painting styles, as he experimented with approaches, such as fauvism and cubism.

Experimenting with cubism. White and Pink Head. 1914. Henri Matisse. Oil on canvas. Credit: Centre Pompidou/Philippe Migeat.

The format of the exhibition also provides insight into Matisse’s artistic process. The many drawings and sketches (often from private collections) reveal the steps before the creation of a final painting. You can feel Marguerite’s personality even through the minimal lines.

A personality captured in its essence. “Marguerite.” 1945. Henri Matisse. Charcoal on paper. Credit: Private Collection/© Jean-Louis Losi

The photographs of Matisse and Marguerite show how important she was to the family and to his creative process and how dedicated she was to his vision.

Photograph of Matisse, his wife Amélie, and Marguerite. 1907. Unknown Photographer. Credit: Archives Henri Matisse

Having essentially grown up in a studio, it was no surprise that Marguerite took up painting as an adult. The exhibit includes some of her work as well as her foray into fashion design.

“Self-Portrait.” 1915/1916. Marguerite Matisse. Photo credit: Meredith Mullins.

One of Marguerite’s fashion designs. Photo © Meredith Mullins.

However, most of her energy went toward managing her father’s business and, after his death, to continuing to promote his work and honor his legacy. She clearly treasured the deep and precious bond with her father.

Gabriele Münter (1877–1962)

Gabriele Münter’s name is perhaps not as well-known as the name Henri Matisse, but her work has a compelling compatibility to Matisse’s exhibit, with haunting similarities. The two monumental shows together provide a unique glimpse into the influences and innovation of this pivotal period of artistic expression in Europe.

“Portrait of Marianne von Werefkin.” 1909. Gabriele Münter. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

Münter is considered one of the most important of women artists in the genre of German Expressionism; although she, like Matisse, experimented with many styles and techniques during her career.

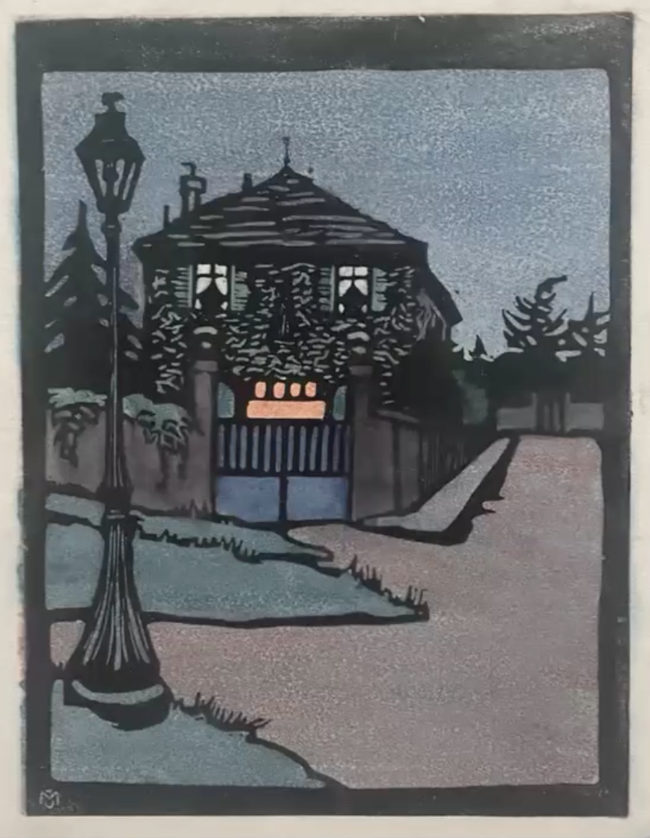

“Little House Bellevue.” 1907. Gabriele Münter. Linocut on Japanese Paper. Photo credit: Meredith Mullins.

The exhibit of 150 works reveals her wide range of artistic mediums and a prolific dedication to her art over six decades, including paintings, engravings, photography, and embroidery.

She began her serious art study in 1897 in Dusseldorf, but found the teaching “uninspiring,” particularly as taught to women, who, at that time, were newly accepted to art schools.

Following an independent international path, she visited the U.S. with her sister in 1898 and recorded the journey in her new medium of photography, showing a particular interest in the people of the southern U.S.

“Three Women in Sunday Dress (Texas).” June 19, 1900. Gabriele Münter. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

In a way, she was returning to her roots, as her parents had emigrated to Tennessee in 1848. This life of travel and freedom was enabled by family money (inherited when both her parents died relatively young).

She moved to Munich in 1901 and entered the academy linked to the Association of Women Artists, but soon transferred to the more progressive Phalanx art school, known for being open to emerging art trends. It is here that she met her future partner Wassily Kandinsky, who was a teacher at the school.

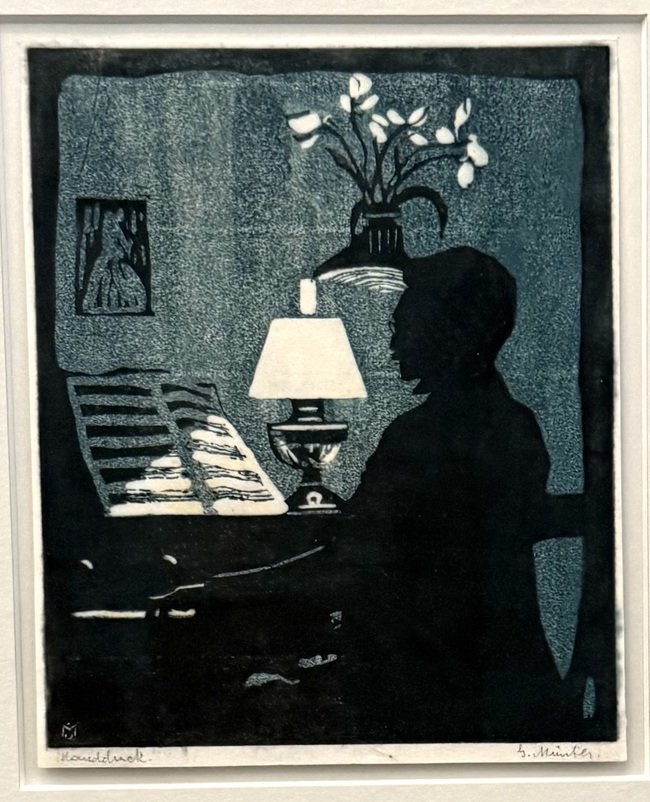

“Kandinsky at the Harmonium.” 1907. Gabriele Münter. Linocut on Japanese Paper. Photo credit: Meredith Mullins

Initially, the school was focused on impressionism, encouraging artists to be spontaneous in their outdoor surroundings by responding intuitively to subjects, nature, and light.

She and Kandinsky traveled extensively from 1903 to 1908, perhaps to escape the fact that Kandinsky was going through a divorce with his wife. True to Münter’s style, she captured the spirit of the people of these different cultures in paintings and photographs.

Street Life in Tunisia. 1905. Gabriele Münter.

Münter and Kandinsky came to Paris in 1906 and soon moved to Sevres. Münter also kept an apartment in the 6th arrondissement.

Mûnter’s talent for the linocut process. “Aurélie.” 1906. Gabriele Münter. Linocut on Japanese Paper. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

As chance would have it, Michael and Sarah Stein also lived in her building. This serendipitous meeting gave her a door into the Stein world, a family of important collectors, who coincidentally were ardent supporters of Matisse. She was most certainly inspired by their apartment walls covered with the paintings of Gauguin, Bonnard, Cézanne, Picasso, and, of course, Matisse.

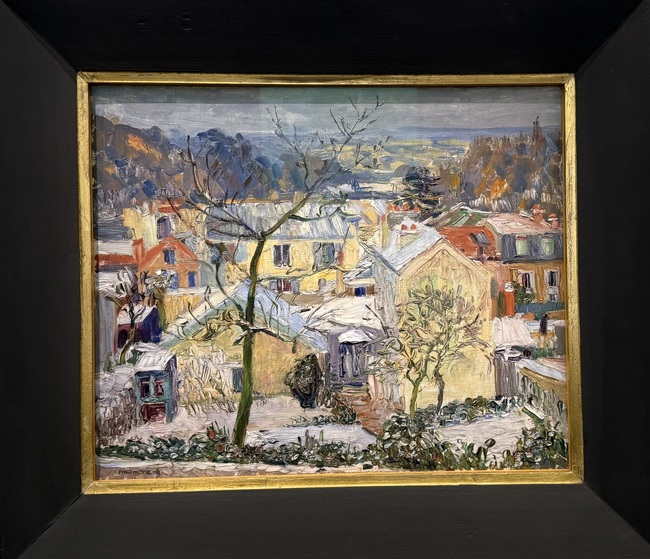

Her paintings of Sevres were inspired by the impressionists. “View from the Window in Sevres.” 1906. Gabriele Münter. Photo credit: Meredith Mullins.

Münter and Kandinsky returned to Munich in 1908. Her portraits during this period showed the influence of her time in Paris — a Fauvist approach of bright colors, unnatural skin tones, and simplified forms.

A Fauvist influence. “Listening (Portrait of Jawlensky).” 1909. Gabriele Münter. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

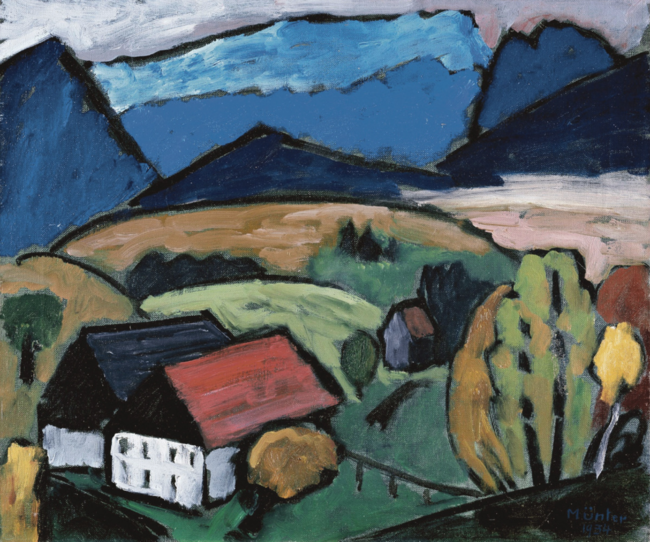

That summer, she and Kandinsky discovered Murnau, a picturesque town by a lake at the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. Their compositions became more primitive, “essentializing” the forms, eliminating detail, and using bright patches of colors less associated with reality.

“Path before the Mountain.” 1909. Gabriele Münter. Photo credit: Meredith Mullins

Münter bought a house near Murnau for their new life of painting and gardening, where they decorated the stairs, walls, and furniture with folklore-like images.

“Interior of Murnau.” 1910. Gabriele Münter.

As their work evolved, they split with some of their former artist group and formed two new groups — the Munich New Artists’ Association and the Blue Rider group.

“Dragonfight.” 1913. Gabriele Münter. Oil on canvas. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

These new collaborations better reflected their emerging style of “abstracting content,” a spiritual fascination for nature, and an appreciation of children’s drawing styles for their “authenticity.”

Münter experimented with copying children’s drawings to “unlearn” her own artistic practice. “Sleeping Child (Green on Black).” 1934. Gabriele Münter. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

During the First World War, Kandinsky returned to Russia and Münter sought exile in Scandinavia. Münter returned to Germany after the war and focused on her favorite technique . . . drawing.

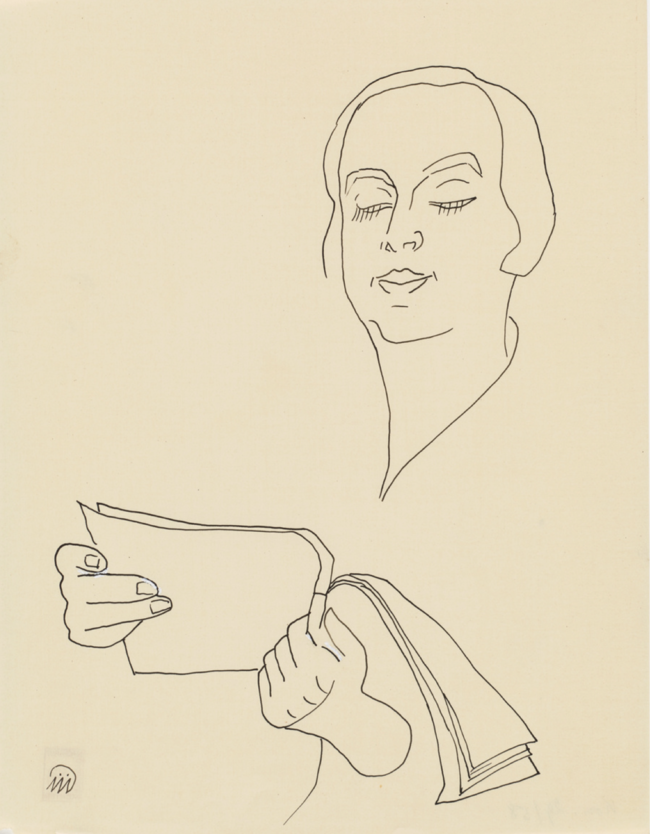

An economy of lines. “Poet E.K. Reading.” 1926/1927. Gabriele Münter. India Ink and white gouache. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

After Kandinsky made his final departure to Russia and married again, Münter returned to the Murnau house and a period of intense creation. She lived in Murnau until her death. The house is now a museum.

Her work always had an intimate quality, whether landscapes or portraits. “View over the Mountains.” 1934. Gabriele Münter. © Adagp, Paris, 2025

DETAILS

Both exhibits at the Musée d’Art Moderne run through August 24, 2025. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 am until 6 pm (Open late on Thursdays.) Reservations are advised.

Lead photo credit : “Portrait of Marguerite.” 1918. Henri Matisse. Oil on wood. Credit: Norton Museum of Art

More in Matisse, Musée d’Art Moderne