A Visit to the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On the eastern tip of the Île de la Cité sits a monument which everyone should visit, but which is often missed. That’s hugely ironic because its purpose is remembrance.

The Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation was opened in 1962 by General de Gaulle, and its stated aim was to honor the memory of the 200,000 French citizens deported from France to Nazi concentration camps in the Second World War: 75,000 Jews, at least the same number of Résistants and members of all the other groups persecuted during that dreadful time: gays, Roma and Sinti people, Jehovah’s Witnesses, the disabled.

General Charles de Gaulle in 1945, Public Domain

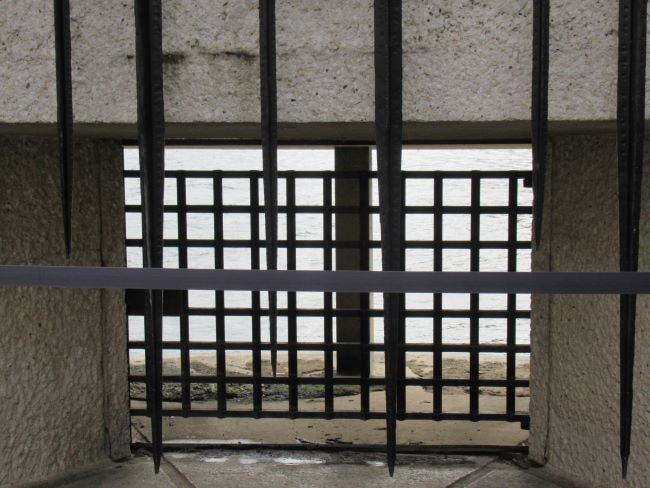

First impressions are bleak, intentionally so. Steps lead down to a cold little stone courtyard and the first thing you see is a metal portcullis through which you can look out onto the River Seine. You are standing just where some of those who had been rounded up for deportation were made to wait, “in the dark and the fog,” for the boat which would transport them away from Paris. Yes, it’s like looking through the bars of a prison. And it is no coincidence that this site, a former morgue, was chosen for the memorial.

View of the Seine from the Memorial. Photo credit: Marian Jones

The architect Georges-Henri Pingusson designed every aspect of the memorial to reflect the cruelty and degradation to which the deportees were subjected. Narrow steps, invoking claustrophobia, lead down from the courtyard into the crypt itself, where a circular plaque on the floor states: “They descended into the mouth of the earth and they did not return.” Here is the Tomb of the Unknown Deportee, where the body of a prisoner from the camp at Neustadt is buried, representing all 200,000 deaths. Here too is an eternal light, shining in the center of the space. A long narrow corridor has a single light burning at the far end, which reflects the 200,000 crystals embedded in the walls, each symbolizing a lost life

Tomb of the Unknown Deportee, Ardfern at Wikimedia Commons

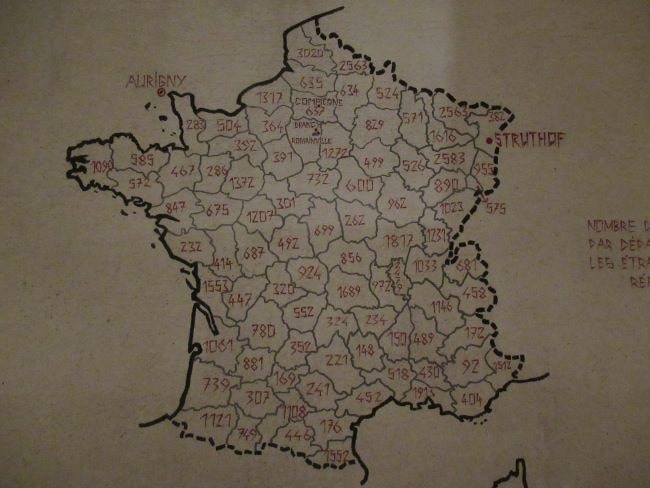

This lower level is dedicated to remembrance and reflection. The upstairs is set out more like a museum, with the aim of informing visitors about the horror of l’enfer concentrationnaire (the hell of the concentration camps). In the first room, each of the four walls displays the facts and they speak for themselves. A map shows the numbers deported from each département and not a single space is blank. From every département, in the German-occupied north of the country, but also in Vichy France, hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people were rounded up and sent to the camps.

A map at the Memorial shows the numbers deported from each département. Photo credit: Marian Jones

On another wall is a map showing the location of some 300 camps, from the familiar such as Mauthausen, Buchenwald, and Auschwitz Birkenau to the largely unknown. In little towns all across Germany, the Low Countries, Austria, Poland, and further north and east, horror was unfolding: Janowska, Belzec, Orianenburg, Koldichevo, Amstetten, Westerbork, to name just a few. Two lists on a third wall explain that some were death camps, others forced-labor camps. A text on the fourth wall explains: these statistics, which are “rigorously authentic,” are not here to incite hatred against people, but rather against la fanatique idéologie which led to these horrors. It is stark to see, but without the facts, how can you claim to be truly reflecting?

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. Credit: Archipathist at Wikimedia Commons

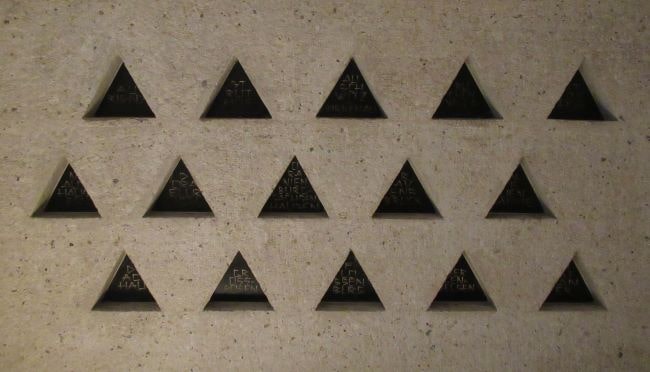

A corridor full of informative displays loops round the upper level. The degradation to which deportees were subjected is spelt out. On arrival, they were stripped and disinfected, had their heads shaved and were given a blue and white striped uniform and serial number, which they were required to learn by heart in German and wear on the left-hand side of their jacket. Prisoners were classified on arrival and forced to wear a colored triangle denoting their “category”: red for those who had been arrested for political reasons, purple for Jehovah’s Witnesses, pink for homosexuals. For Jews, a second, yellow triangle was added. The daily roll call, humiliating in itself, was an ordeal for many prisoners, weakened by the dreadful conditions and the labor they were forced to do. It was held in all weathers, could last several hours, and prisoners who moved were struck by the guards. It was not unknown for prisoners to collapse and die before the end of the roll call.

Death was everywhere. The greatest killers were exhaustion and hunger. Those selected for labor were worked without mercy and those who became unable to continue were sometimes transferred to the death camps. At some death camps all arrivals were sent straight to the gas chambers, at others the Jews were singled out and murdered on arrival. Sometimes a log was kept, recording the bare facts of a prisoner’s experience. Raymond Odouard, for example, was arrested in Triers in February 1943, transferred to Buchenwald a month later, transferred to Lublin in February 1944, and then to Flossenburg, where he died in October that year. This stark description of the last 22 months of Raymond’s life leaves so many questions unanswered.

The photographs are harrowing. One, positioned right at the end of the room, and enlarged, is unforgettable. It shows a family group, old and young, gathered in a sepia print which speaks of long ago. Normally, you would wonder what became of them all, but in this case, of course, there is little need to ask. What makes it so memorable is the little blonde girl in the front because her image has been taken out, illuminated and enlarged. She attracts your immediate attention, one individual child to represent so many victims.

There are momentary glimpses of prisoners being able to cling to their humanity. Those who had been doctors or nurses tried to offer care to those who needed it most. Some prisoners joined together in clandestine resistance committees, encouraging each other not to give up hope. In Trier, one prisoner, Father Jean Daligaut, painted a poignant image of another prisoner onto a scrap of newspaper, using straw from his bedding as a brush and the few makeshift colors he was able to find: green and black scraped from the damp walls, yellow rust from a shovel, and white from a precious piece of soap. Another deportee, Reverend Father Michel Riquet, wrote that keeping one’s beliefs in the camp, “this realm of hatred,” was “a triumph for charity.” He did survive and on returning to Paris joined the Réseau du Souvenir (Network of Remembrance) which was behind the creation of this memorial.

15 black triangles at the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. Photo credit: Marian Jones

To learn these things is to understand a little better. Back downstairs are two tiny chapels of remembrance. Set into the grey façades are 15 black triangles. They are urns, each containing earth and ashes from one of the death camps and inscribed with its name. Here, as everywhere in the memorial, those who designed it hope that you will take time to consider in silence what it is they hoped to achieve: remembrance of all those deported from France during World War II and reflection on the lessons their tragedy teaches us for today. Above the exit you will see the words written at many Holocaust memorial sites: “Forgive, but never forget.”

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation

Square de l’Île de France

7 Quai de l’Archevêché

75004 Paris

Open every day, except Jan 1st, May 1st, August 15th, Nov 1st and December 25th, from 10 a.m. – 7 p.m. in summer, 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. in winter. Entrance free. Groups of over 10 people should book in advance.

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. Photo credit: Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, Guilhem Vellut at Wikimedia Commons

More in concentration camp, holocaust, Labor camp, Memorial, Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation