John G. Morris: Saying Adieu to a Paris Legend

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

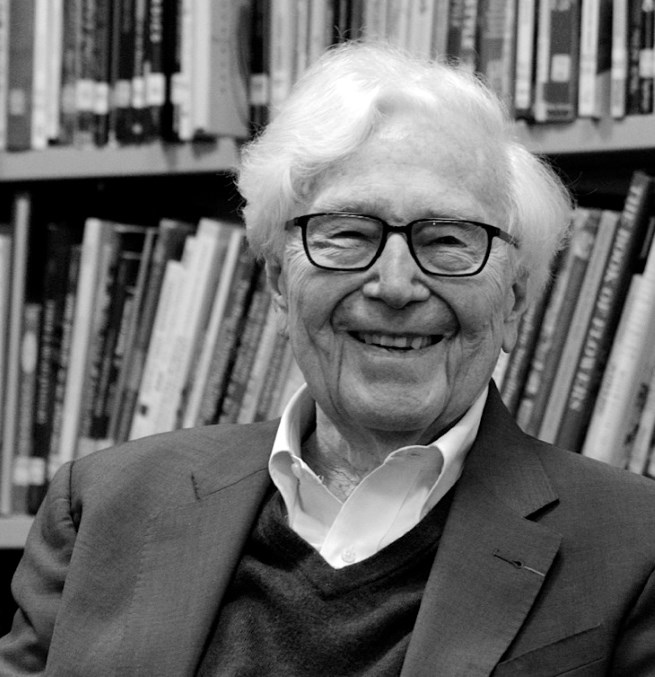

John G. Morris, photo © Meredith Mullins

Word spread quickly last Friday, July 28, of the passing of John G. Morris, a Paris legend and one of the most influential picture editors in the world of photojournalism.

Tributes poured in from friends and colleagues—words like treasure, titan, hero, icon, pacifist, mentor, political activist, and giant of photojournalism, as well as adjectives such as courageous, kind, generous, fervent, forceful, charming, thoughtful, gentle, humble, and inspiring.

Mr. Morris lived to be 100—a century filled with life and love, war and change. He celebrated his 100th birthday last December 7 at a party at his home in the Marais—although he had to skype in from the hospital as he had fallen ill just before the festive day.

A who’s who of writers, photographers, publishers, and political activists, as well as his family and his loving partner Patricia Trocmé cheered him on and cheered him up.

He recovered, proving his resilience and showing his positive spirit. As was his nature, he thanked everyone for encouraging him “to hang around a bit longer.” It was not yet time “to close up shop” as he liked to put it.

Some of us thought he would live forever. Some even wished him good luck for the next 100 years. He had that air of immortality.

When someone dies at age 100, after living such a full life, the feeling of sadness is deep and the friends who grieve are many; but, with John, there is also a legacy of inspiration. He was a man who was able to shape history and make a real difference in the world.

A Life Well Lived

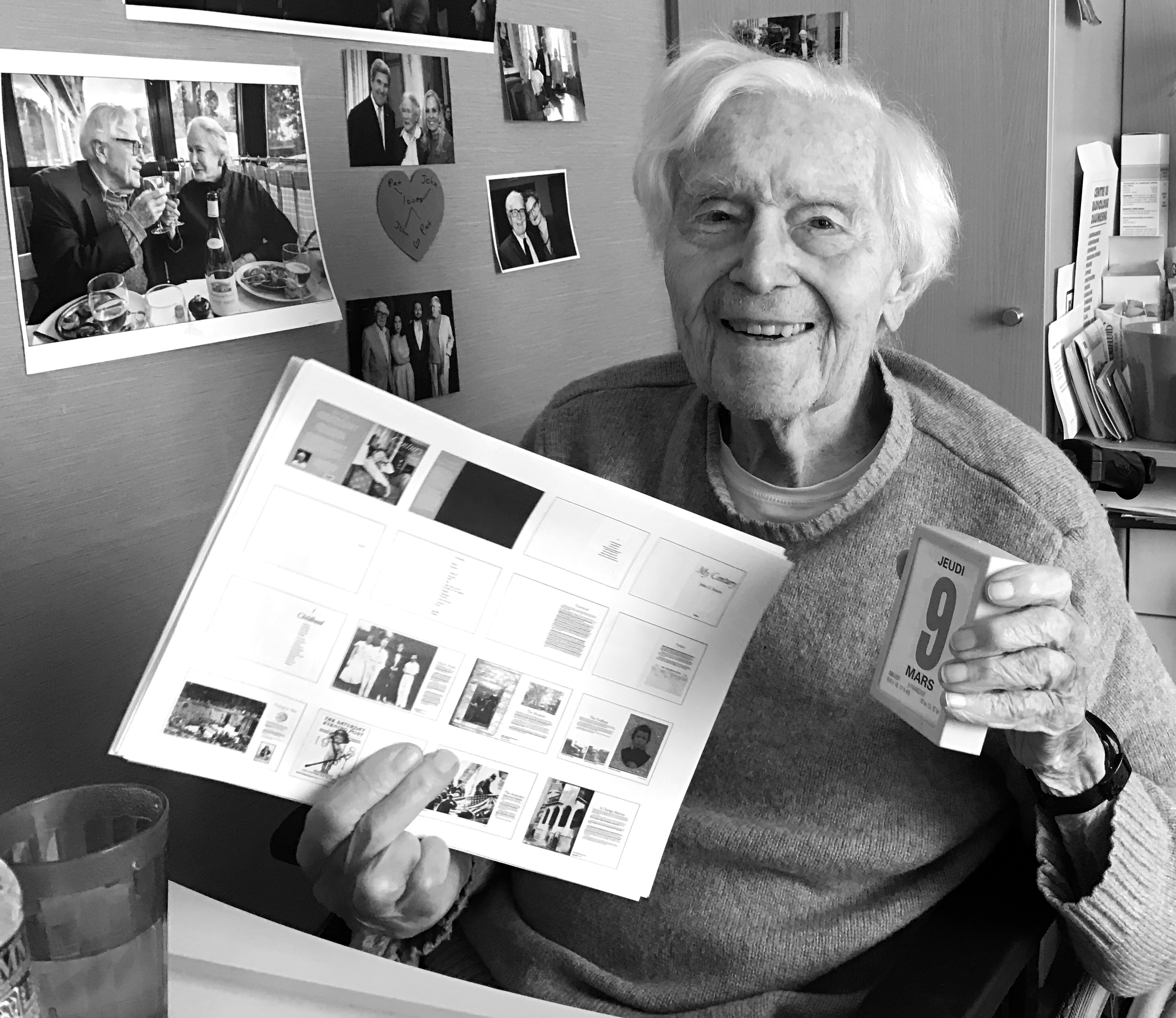

John Morris celebrates the completion of the mock up of his book My Century (March 9, 2017). Photo © Meredith Mullins

Morris graduated from the University of Chicago in 1938 and went to work in the mailroom of Time/Life publications where he soon became Life Magazine’s Hollywood correspondent and then the London picture editor.

It was in his London post that he made history as the picture editor during the turning point of World War II. He assigned two Life photographers to cover the June 6, 1944 D-Day landing, and, after a nerve-racking wait, received the precious rolls of Robert Capa’s film of the historic action.

There is controversy about what happened next. It is often reported that much of Capa’s film was ruined in the rush of processing by a lab assistant. The mystery is still unsolved. The bottom line is that Morris salvaged “the magnificent 11”—eleven grainy, dramatic frames that became the iconic record of that day of loss, courage, and triumph.

Mr. Morris explained in a 2014 interview, “I used to take the blame for the loss of Capa’s D-Day film. In recent years I’ve learned to say that I’m the one who saved the 11 frames.”

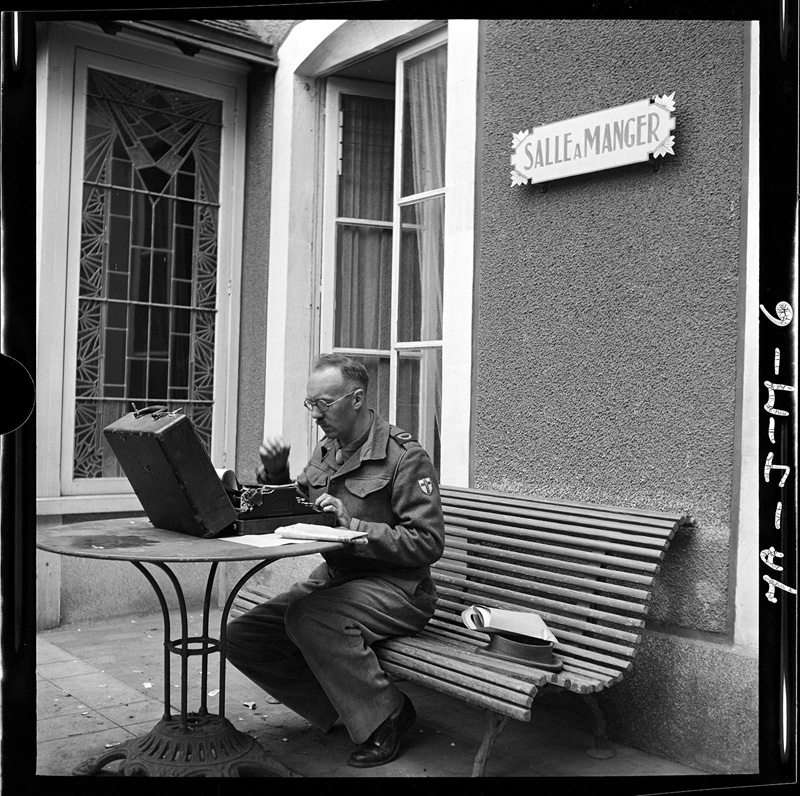

Six weeks after the D-Day landing, Mr. Morris joined Capa and other Life photographers in Normandy. Although Morris never had an interest in being a photographer (he is quoted as having said, “I don’t take pictures unless the photographer doesn’t show up.”), he borrowed a camera and made a series of powerful photographs, showing a very human side of the combat zone after the invasion.

From the book Quelque Part en France, one of John Morris’ photographs from Normandy after the D-Day invasion. Photo © John G. Morris/Courtesy of Contact Press Images.

A book of this work, Quelque Part en France (Somewhere in France), was published in 2014, and the work was exhibited at the International Center for Photography in New York and at several sites in France. With this new attention to his photographic talent, Morris joked that he was the world’s oldest emerging photographer.

Throughout his career, Mr. Morris worked for most of the influential photojournalism publications and organizations, such as Life Magazine, The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, and Magnum Photos. He also worked with some of the best photographers of the time: Robert Capa, Bob Landry, W. Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson and so many more giants of photojournalism.

He was a vocal advocate for photography being as powerful as the written word in publications, and he sparred with editors about the importance of telling the truth, particularly in showing the ravaging effects of war. He believed that photojournalists had a responsibility to document events in the most honest and memorable way possible.

John G. Morris, photo © Meredith Mullins

“I have always believed in showing how ugly war is,” Mr. Morris told The New York Times in 2016, “and I have encouraged newspapers to take a realistic view of war.”

When he worked for The New York Times during the Vietnam war, he insisted in placing real images in front of the world, no matter how hard they were to look at. He won his battle to place two shocking Vietnam images on the front page—Eddie Adams photo of a South Vietnamese police official executing a Viet Cong prisoner in 1968 and Nick Ut’s photo of a naked, screaming Vietnamese girl running from a napalm attack in 1972. These images helped change public opinion about the war. Both photographs won the Pulitzer Prize.

Mr. Morris moved to Paris in 1983 and worked for six years as a photo editor for National Geographic. He published his memoir, Get the Picture, in 1998; coauthored Robert Capa: D-Day, published in 2004; received the French Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 2009; received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Center of Photography in 2010; and became the subject of Irish filmmaker Cathy Pearson’s documentary Get the Picture released in 2013.

He remained politically active as an American democrat in Democrats Abroad, attending conventions and hosting many lively meetings at his home, and was an ardent supporter of Barack Obama and Bernie Sanders.

Throughout his life, with war as a central photojournalism theme, he has remained a vigilant pacifist.

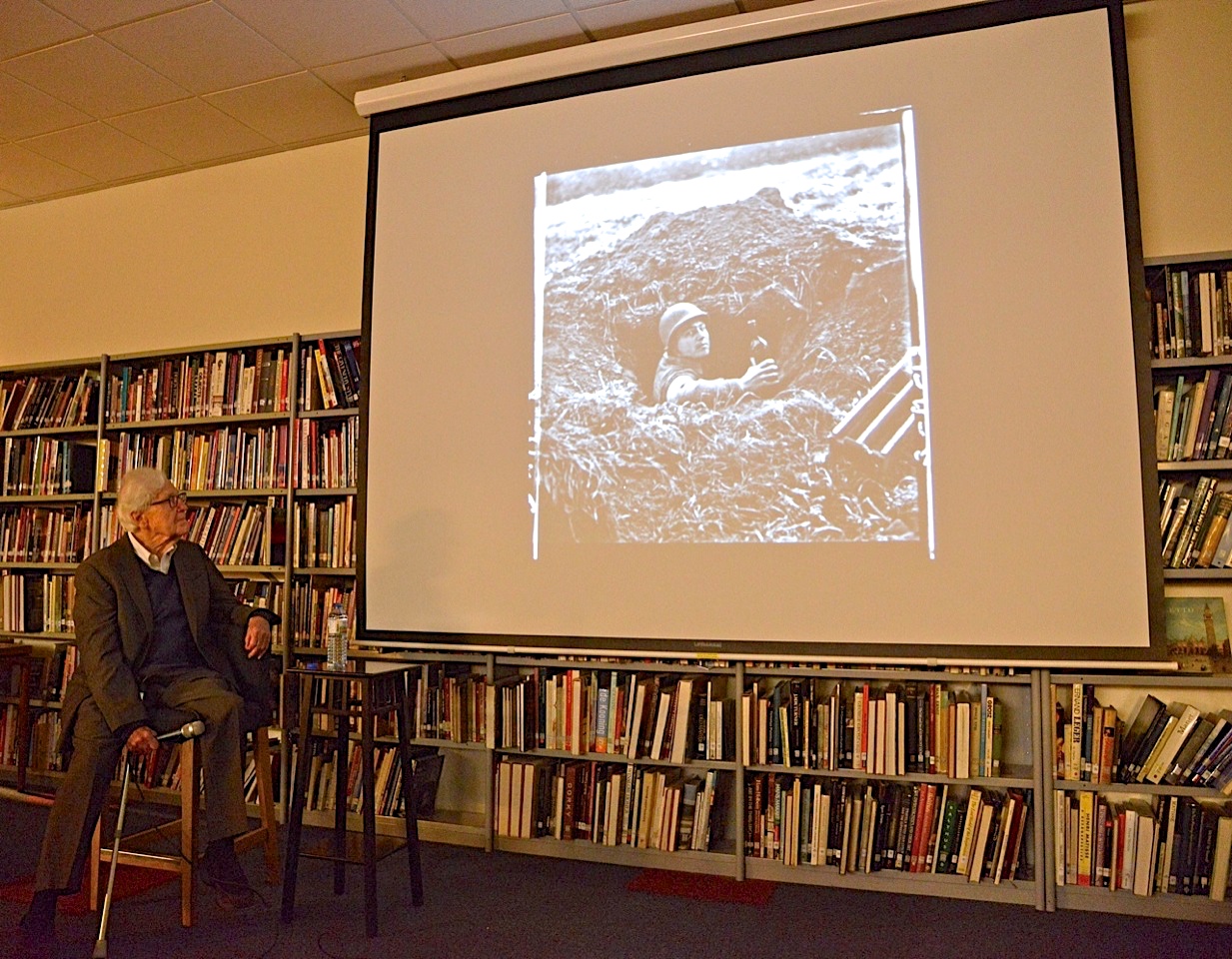

photo© Meredith Mullins

“Why is it that, after all these years of wars being photographed, we still have war?” he asked in a 2016 interview for Magnum Photos. “Does our coverage of war tend to make heroes of soldiers? Is that the right thing to do?”

He always believed that photographs had to have passion and human feeling, as well as something to say.

His words to photographers everywhere (from a New York Times interview) are worth etching into memory:

Timing is all important in photography. Not just the timing of the shutter itself, but knowing when to work and when not to work. When to photograph and when not to photograph.

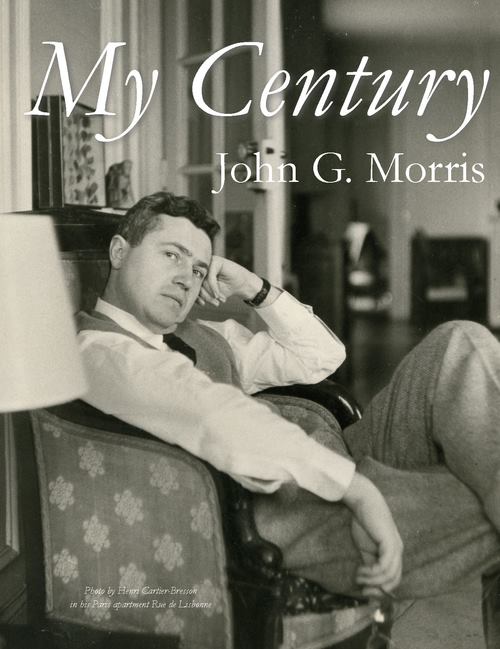

My Century by John G. Morris

Great photographers have to have three things. They have to have heart if they’re going to photograph people. They have to have an eye, obviously, to be able to compose. And they have to have a brain to think about what they’re shooting. Too many photographers have two of the three attributes, but not the third.”

As a fitting summary of a life that was witness to so many world-changing events, Mr. Morris had just completed an illustrated autobiography entitled My Century.

The book was an important goal for him, a success that gave him a poignant sense of finality, although it has yet to find a publisher.

His other life goal—seeing an end to war—was a goal not to be reached in his lifetime, although not for lack of trying. He led the crusade for peace in many ways.

He may not have succeeded in ending war, an elusive assignment for any one person; but he did succeed in showing the world important truth . . . and in touching the hearts of everyone he met along the way.

For full obituaries, read The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Lead photo credit : John G. Morris, photo © Meredith Mullins

REPLY