An Exclusive Excerpt from “Bonjour Kale” by Kristen Beddard

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Looking for some fun summer reading? Kristen Beddard of The Kale Project has recently published a book called Bonjour Kale, a Memoir of Pairs, Love & Recipes. As featured in the France Today article, “The Nouvelle Vague: Today’s Expats in Paris,” Beddard created enormous buzz (and quite the following) for her efforts to reintroduce kale– a légume oublié (forgotten vegetable)– to France. The movement gained such momentum that The New York Times called Beddard “the kale crusader.”

In this exclusive excerpt from her new book, Beddard describes her first experience exploring the city’s outdoor markets when she and her husband Philip moved to Paris. Enjoy! Bonjour Kale is available at fine retailers and online at Amazon.

*************************************

Philip and I moved to Paris at the end of August 2011. The plane had barely touched ground at Charles de Gaulle when I started asking when we would be able to take our first trip to an outdoor market. As with most cultures, in France, the market began as a common place for people to buy and sell various goods, from produce, meat, and fish to housewares, clothing, and more. It was the original third space for people to congregate, share ideas, and spend time together. The first market in Paris dates back to the fifth century, when the city, then occupied by the Romans and called Lutetia, was located on the Île de la Cité in the middle of the River Seine. Today there are roughly eighty outdoor and covered market destinations in the city, most open from eight thirty in the morning to one thirty in the afternoon. They are still packed with people sharing their love for fresh food and ideas. If there was one thing I was most excited about for our new life in France, le marché was it.

On our second day, we needed food, so I grabbed my straw panier—my bag for shopping—and dragged Philip out the door. Everyone says the best way to tackle jet lag is by getting outside, right?

Our temporary apartment, where we lived for a month while we looked for more permanent accommodations, was located on the border of the Seventeenth and Eighth arrondissements, and only a five-minute walk from the neighborhood market, Marché Poncelet.

[The Kale Project video by Dark Rye]

Walking down boulevard de Courcelles toward place des Ternes, the Arc de Triomphe peeked out in the distance. The avenue des Ternes was a busy main road, with noisy traffic and chain stores, and was a stark contrast to the small, pedestrian-only rue Poncelet. As if I’d pulled back a curtain and gone back in time, the modern city rush dissipated behind me as I walked Poncelet’s quaint village tableau.

The corner broke into two streets, rue Poncelet to my right and rue Bayen to my left, encompassing more than a dozen small shops. The grocer on the corner featured the in-season cèpes, large fairy-tale-like porcini mushrooms. Sold by the container, their fat tops and thick trunks (which are sometimes filled with insects) were cut in half to display clean insides. The mushroom halves were lined up next to a matrix of dark purple figs, so tender and ripe their skin was beginning to split near the tops. Bumblebees swarmed over each fig tip, hoping for a tiny taste of the gooey, pink fruit.

Taking in the warming scents and rowdy noises, I noticed a boucherie with cow tongues and hooves in the front window case. A rabbit with its brown fur sticking out hung from the ceiling, with a sign clipped to its foot, “Sold.” Men behind the counter wore bloodstained white aprons and worked on wooden counters, dented from years of pounding meat. A handwritten chart hung on the wall, outlining where each cut of meat came from and they rung up every purchase on an antique cash register.

Beads of sweat dripped from the poulet man’s brow as he placed chickens, pink with goose-bump skin, onto rotating roasting spits.

They revolved in rows of eight, attached to a large wall of flames, while potatoes, onions, and peppers cooked below, soaking up the juices dripping from the birds.

Young men outfitted in knee-high, rubber rain boots and bright blue jackets and aprons circled the outside tables of the poissonnerie, shoveling ice chips onto trays of crevette rose (pink shrimp), oursin (sea urchin), and bulot (whelk) that spiraled like the turret of a castle. As each fish was filleted, the heads collected in buckets on the ground, wet from melted ice.

Vendors hollered playfully to each other and at passersby, shouting reasons to buy their bright red strawberries or crisp, green-tipped endive over anyone else’s. Being in this market was magical, like I was part of a sacred daily ritual. We were all there with the same goal in mind: to decide what we would take home that day to nourish ourselves and our families. It felt more real than going to a supermarket and thoughtlessly dumping king-size packages into a shopping cart. The purchases at this market were deliberate and intentional.

Old French grandmas, or bonne-mamans as they are affectionately called, impeccably dressed with not a strand of hair out of place, toddled past, inspecting each piece of produce.

“Monsieur, I would like some mirabelles, please,” a bonne-maman said, asking for the small, golden plums that are ripe every September.

Dressed in a fur coat with an elegant walking stick at her side, she stood her ground at the front of the stand, making sure no one cut in front of her.

“Bonjour, madame, of course, but today we are selling them on special,” he exclaimed, hoping that his special price was better than the other man’s price a few stands away.

“That’s wonderful, monsieur,” she replied, moving her cane a centimeter to the right, maintaining her balance against the rush of shoppers behind her. “But it is just me and my husband. It is not possible to eat all of these in only a few days!”

“Why, of course, madame. I will give you a poignée, a handful for today, they will be ripe and sweet, and then you will have another handful for later this week, which will ripen over time,” he explained, feeling through the mound of yellow-green fruits, searching for the perfect pieces for today and for later. The sweet granny was satisfied.

The maraîcher knew best. Initially, not being able to pick out my own produce stressed me out. I didn’t know all the words for everything or how to ask for what I wanted—at least not clearly and succinctly. And when you have a line of anxious and impatient

French women sighing behind you, it becomes even harder to speak correctly without a frog in your throat. But I learned to let the market men and women choose. After all, it is their métier, profession. They know better than I do when a peach will be ripe or which apples have a sweeter bite.

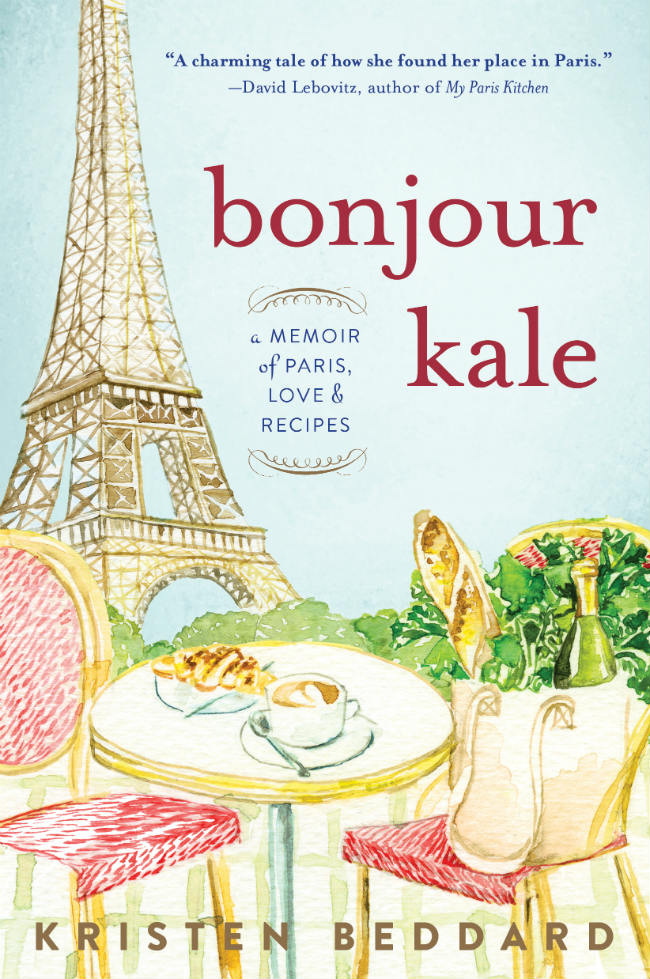

Book cover for “Bonjour Kale” by Kristen Beddard. Credit: Jessie Kanelos-Weiner

Our first market excursion was exciting. I loved the energy, the options, and the smiling people, laughing and so joyful to share their food with you. For my first cooking effort in Paris, I decided not to be very adventurous, but I did want to prepare something using fresh ingredients: salmon, roasted potatoes, and a kale salad. And that’s when it hit me.

“Philip, do you know what I haven’t seen yet?” I asked, stopping midstep by the last vegetable stand on the street. “Kale. Not one leaf.”

Philip, still dreaming of the gooey Saint-Félicien Tentation double-cream cheese we’d just purchased at the fromagerie, turned.

“You’re right. And I don’t know how to say ‘kale’ in French.” He took out his phone and used Google Translate. That was the first time I saw the name chou frisé. Chou translates to cabbage and frisé translates to curly. That is what kale is and what it looks like, so the translation made sense to me. We approached the last vegetable stand and asked for chou frisé, The man listened, walked into the shop, and came out with a green, crinkly, and round…savoy cabbage.

“No, Philip,” I whispered, trying to hide that I was, clearly, the new American on the market block. “That’s not it. That’s not kale. You know that.”

“Monsieur, yes that is chou, but do you have one that is just the leaves? A darker color and curly?” Philip asked in French.

The man stared at us and tore off the outer leaf of the savoy cabbage. “Voici. Here, this is just the leaf. It is curly and chou,” he replied, deadpan.

Not wanting to frustrate or insult the man, we paid for the cabbage, and I dumped it into my bag, knowing it would not be part of that evening’s meal. I moped off to the lettuce man and would make a regular salad instead. While waiting in line for the lettuce,

I did a reverse Google Translate. “Savoy cabbage” in French was chou de Savoie. Something did not make sense. So what was the real French translation for kale?

Lead photo credit : Author Kristen Beddard at the market with Joel Thiebault. Photo credit: Pierre Olivier