Inside a Parisian Apartment: Georges Perec and Other Paris Peeping Toms

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Wanna play “house”?

Within Georges Perec’s Life A User’s Manual, published in 1978, the Paris-born Perec plays house with the tenants of his fictional apartment building at 11 rue Simon-Crubellier, peering into their lives like an overgrown child with a doll house. He metaphorically peels away the façade of his pretend Parisian apartment and describes the lives, stories, and possessions of its tenants, both past and present, in precise detail.

In Perec’s world, time has stopped at 8pm on June 23, 1975. The characters in this corner of the 17th arrondissement are like motionless puppets in a play house until Perec introduces us to each character and gives them a story line. From the relic-strewn cellars to the servant’s garrets pitched high under the roof, from crisp architect-designed suites to a simple homespun room for a single girl, from the lowly contents of one tenant’s cupboards to the provenance of an Assyrian stone lion – Perec’s imagination takes readers to the edge of infinity. The author leads the reader into one character’s flat, then once guided into a living room, he focuses on a postcard on the wall and further zooms us into the subject of the painting and weaves a story about the historical characters within. When we are well and truly engrossed in Perec’s tangent, he zooms us out and on to the next chapter of La Vie mode d’emploi.

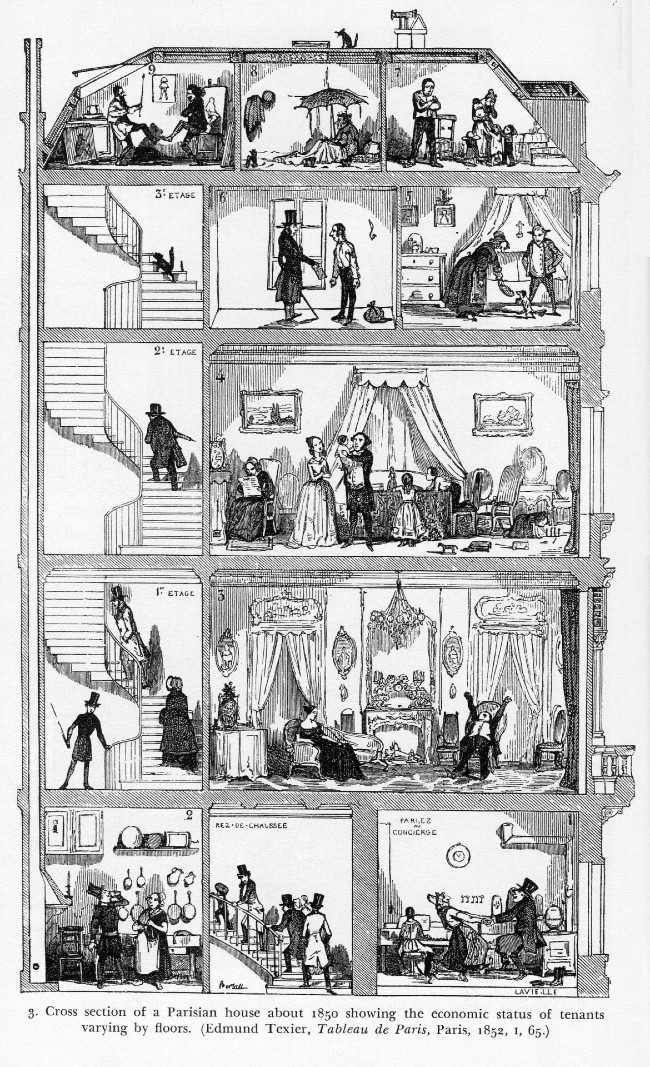

“Les 5 étages du monde parisien”, Edmond Texier, Tableau de Paris. Public domain

Amid the 100 bite-sized chapters, Perec introduces us to the anthropologist, Marcel Appenzzell and his fixation to live with the Orang-Kubu tribe; the widower Sven Ericsson, and his all-consuming plot to avenge the death of his family; the 11-year-old acrobat who wouldn’t come down from his trapeze and causes 53 members of his audience to swoon.

It is the death of Bartlebooth that is the catalyst to Perec’s story, for tonight is the night that the heart of the tremendously wealthy English eccentric stopped ticking. Bartlebooth had devised for himself the ultimate hobby and a handful of the tenants of 11 Rue Simon-Crubellier find themselves embroiled in his pastime. Bartlebooth and these neighbors take part in the fabrication and demolition of jigsaw puzzles from beginning to end. The idea of the jigsaw is analogous with Perec’s apartment block as a whole. A single jigsaw piece means nothing until it is put into place to complete a picture, and Perec’s fictional apartment block becomes ever clearer as more pieces are assembled.

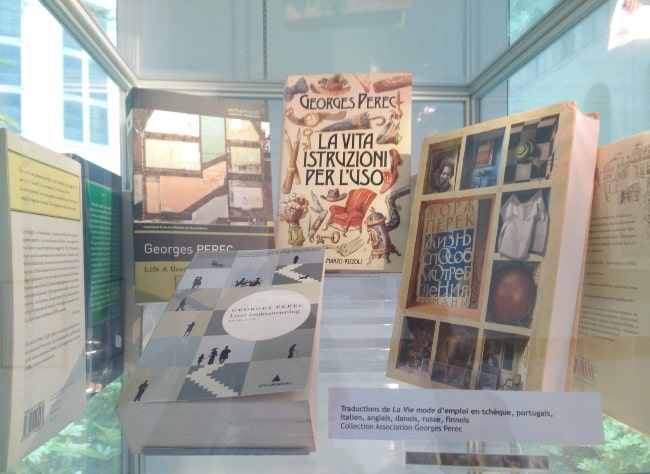

An expostion of Perec’s book translations of life instructions for use in Czech, Portuguese, Italian, English, Danish, Russian and Finnish. Image © Flickr, ActuaLitté (CC BY-SA 2.0)

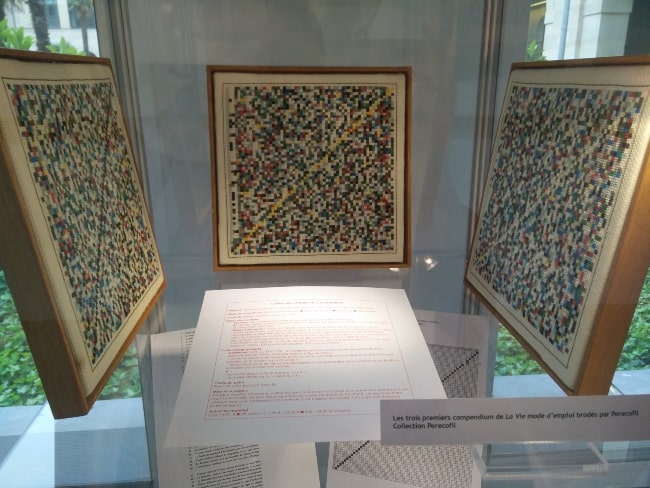

While the theme of jigsaw puzzles is an overriding one In Life A User’s Manual, the book as a whole is interspersed with puzzles, murder mysteries and allusions, logic and formulas. Perec was a famed member of “Oulipo” —a French literary movement in which writers use explicit constraints to create their texts. In his 1969 book A Void (La Disparition), Perec wrote 300 pages without the letter E. In Life a User’s Manual, Perec has utilized a magic square of 10 which yielded the book’s 100 chapters. Each of Perec’s squares contained one character coupled with a characteristic, an action or a place taken from a predetermined list of about 40 units such as shapes, colors, art, activities, allusions and quotations. Such a grid aided Perec’s mind-blowing imagination, but also reined it in. The grid of the apartment building is found in the book’s appendix. For those curious, the order of the chapters echoes the moves allowed by a knight in chess. The next chapter is always two squares away and one square the other way from the last.

Image © Flickr, ActuaLitté (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Georges Perec won the Prix Medici for Life A User’s Manual, however the translator, David Bellos, should be applauded for taking Perec’s original ideas and implementing them in English.

Georges Perec died in 1982 at just 45 years old. Apart from the Prix Medici, Perec was also awarded with the Prix Renaudot in 1965, the Prix Jean Vigo in 1974 and honored with an asteroid named after him, a street in the 20th arrondissement, and a postage stamp. Devoted fans still try to pinpoint where 11 rue Simon-Crubellier is to this day.

It’s obvious that the director of Amelie, Jean-Pierre Jeunet was influenced by George Perec’s cross-section of the Paris apartment. Both trace the interconnections between the tenants of a typical Parisian apartment block. This 2001 film introduces us to the Glass Man who paints nothing but Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party while all his furniture is padded to avoid injury. His video-cam is focused on the clock across the street. The bully, M. Colignon, wears old-man slippers, striped PJs and has many decanters of liquor. The concierge, Madeleine, tends to a large portrait of her missing husband, has kept many love letters and has sent her dog to the taxidermist. Amelie herself likes the feel of putting her hand in a tub of lentils and the crackle of a crème brûlée. All this detail is just a fraction of what Perec is capable of.

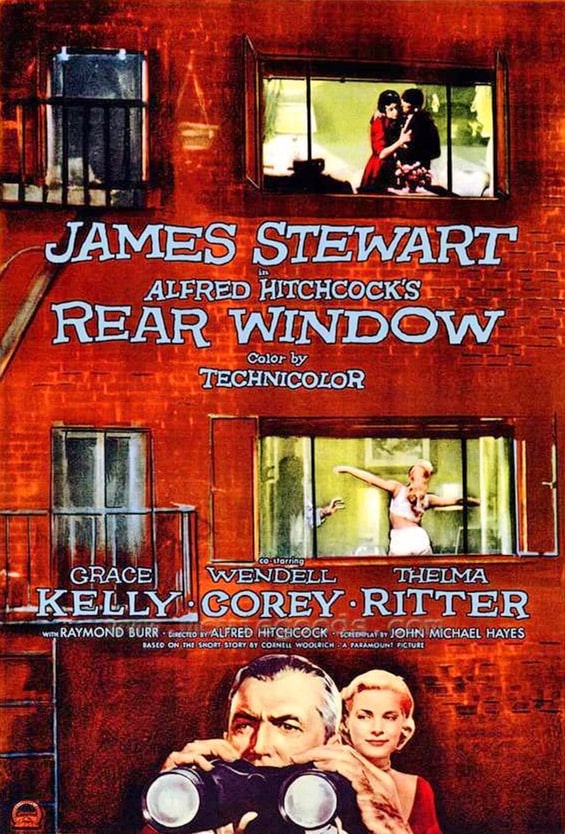

Another voyeuristic endeavour fully reminiscent of Hitchcock’s Rear Window is the art photography book Paris Windows by Gail Albert Halaban, 2014. The introduction to Albert Halaban’s book by famed photographer Christian Caujolle states that due to the stacking of a city’s inhabitants into apartments (in this case Paris), one cannot help but be overlooked by one’s neighbors. They interfere with your gaze and you, theirs. Photographed after dark, Albert Halaban’s surveilled subjects don’t reveal much in their sad, ambiguous apartments, but we can’t help but fill in the blanks regarding their private lives. Fortunately, Albert Haliban has directed the residents living across from her camera’s lofty perch, like actors on stage, to create a vague tableau while saving her readers from being total Peeping Toms.

A long time ago, some light-hearted peeping was offered up in Edmond Texier’s 1852 satirical look at the Paris apartment. Texier, a poet, journalist, novelist and the Editor-in-chief of l’Illustration, abundantly illustrated the work titled Tableau de Paris in the early days of Haussmann’s transformation of the Paris streetscape. This cross-section of the typical Parisian apartment embodies what Perec, Gail Albert Halaban, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet attempted in their writing, photography and films.

Purchase the book at your favorite independent bookstore or on Amazon below:

Lead photo credit : Image © Flickr, (public domain)

REPLY

REPLY