Jos Verheugen: A Paris-Based Artist on a Mission

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

How does a trilingual Dutch postdoc performing scientific research at the prestigious Institut Pasteur extricate himself from the minutiae of that research and transform himself into a successful Paris-based artist? As that artist, Jos Verheugen, explains, through the sheer love of painting.

The stocky, ruddy-cheeked Verheugen, 58, is congenial, smart, and direct, with playful, sometimes piercing, eyes. He received a PhD in electrophysiology – the branch of physiology that studies the electrical properties of cells and tissues – with the intention of becoming a university professor. Electrophysiology is essential to, for example, how heart pacemakers work. Among his other research, Verheugen developed new methods of studying the electric potential and calcium levels of cells, and one of his research papers is still cited two decades later. But his heart wasn’t in it. At university, he had always had more friends in the art department than in his own, and even while working at Pasteur, he painted on weekends, until he finally decided to pursue his passion and focus full time on his art. He has no regrets about spending all those years as a scientist but, as he said, simply, “I love to paint.”

“Librement après Mondrian – with tree frogs”. Photo courtesy of the artist – Jos Verheugen

Verheugen, who is a self-taught artist, is steeped in artistic knowledge, but his greatest influences have been Dutch painters, including Rembrandt (1606–1669), Kees van Dongen (1877–1968), and Charley Toorop (1891–1955), all of whom have influenced his portraits, more about which later, and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944).

Verheugen has the organizational skills of a scientist and has always kept detailed journals. During a period in which he had been experimenting with painting animals – he started with frogs – he happened to flip through one of his journals and discovered that he had written, “put animals in geometrical abstract paintings.” It occurred to him to paint animals into the geometrical abstract paintings of Mondrian for a series he calls “Free After Mondrian” (“Librement après Mondrian”). In addition to frogs, he has also painted snakes, sheep, zebras, bulls, birds, and people into such paintings.

Paris-based artist Jos Verheugen in his studio with prototype of a calendar of his paintings of endangered birds / photo by Diane Stamm

Verheugen paints in oil on natural linen canvas and uses only three colors – the same three colors Mondrian used – cadmium red, ultramarine blue, and Naples yellow – plus white, from which he can create virtually any color. He eventually created almost six hundred “Free After Mondrian” paintings, almost all of which have been sold.

Paris-based artist Jos Verheugen in his studio next to a painting from his “Librement après Mondrian” series / photo by Diane Stamm.

While showing me a prototype of a calendar of endangered bird species within his “Free After Mondrian” theme, Verheugen launches into a dissertation on the environment and how the use of pesticides has killed the insects birds feed on during migration. He tells me that Holland has tried to preserve its landscape, and the birds in his paintings, but that seven of the 12 species depicted in the calendar can be legally hunted – “shot out of the sky” – as they migrate over France, even though elsewhere in Europe, they are legally protected. He rails against the powerful French hunting lobby, which he calls “the ARA [American Rifle Association] of France.” Clearly, Verheugen is an artist with a conscience, and with a certain amount of anger over the destruction of the natural environment.

While Verheugen’s “Free After Mondrian” paintings are, as he says, “ludique,” that is, playful, his portraits are anything but.

Verheugen likes to paint big women – women many females struggle all their lives not to be. But he has written of “the delicious attractiveness of a curvaceous female body.” When he talks about portraits of women, he alludes to Lucien Freud’s paintings of a naked Sue Tilley, Freud’s 280-pound British jobs center benefits supervisor by day and his oversize model by night – “Big Sue,” as she became known. In 2015, one of Freud’s paintings of Big Sue, “Benefits Supervisor Resting,” sold at auction for $56.2 million.

Verheugen also talks about how Flemish Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens portrayed women. As one British art critic wrote in 2015, “The well-nourished models in his paintings are routinely described as ‘fleshy’. While they would be unlikely to grace the cover of Vogue magazine today, Rubens’ models were once lauded as the apogee of beauty.”

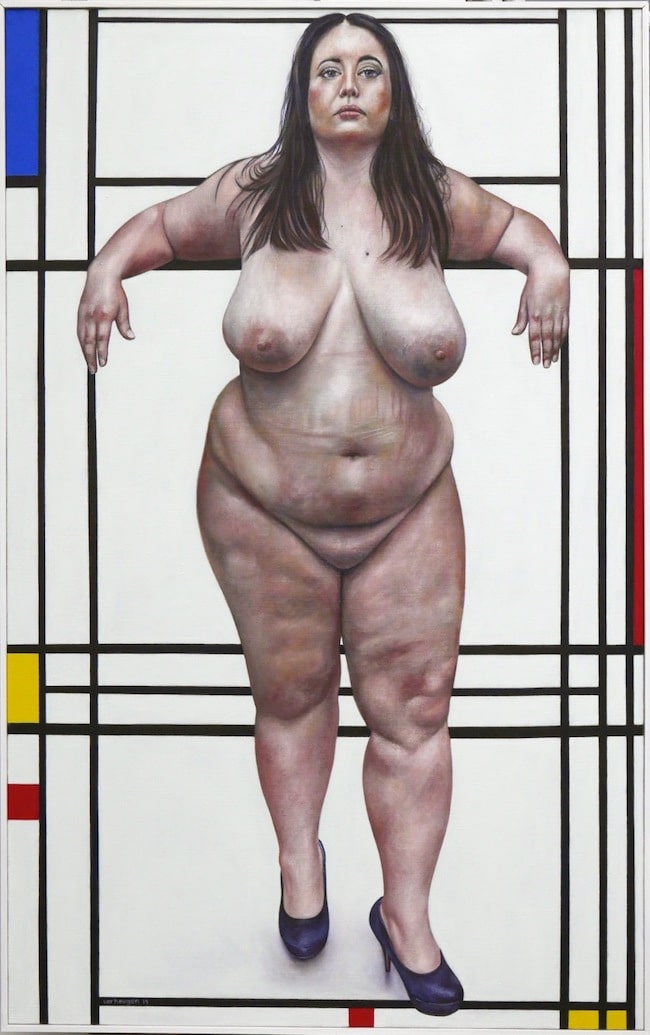

“Librement après Mondrian, with Isabelle”. Photo courtesy of the artist – Jos Verheugen

Of all the works Verheugen cites, there is nothing to suggest current conventional definitions of female beauty. And that is Verheugen’s point. As he explains, “During the Baroque period, the perfect woman had a big ass. The ideal used to be fleshy women with full figures – large breasts and bottoms. But the ideal changes, and now, ‘slim’ is the preferable body, with not too much ass or too much breasts. Where does that ideal come from?”

He answers his own question: “Of course, it’s the fashion industry. I don’t have anything against gay people; many designers are gay. So what do they want to see? They want to see boys. So they make women’s clothing and they want to use women models but not really women’s shapes. And the public is watching them and says, ‘okay, these are the shapes we are supposed to have. And I have this woman’s body.’ So they don’t enjoy themselves or allow themselves to eat properly, so they are unhappy. Photoshopped photos of women who rebuild their bodies with plastic tits and buffed hips – horrible. Horrifying.” He explains that he is on a “mission,” and that mission “is to free large women” – with their wrinkles and cellulite and oversized bodies – “from the stigma society accords to large people and to make people see them as beautiful! Pretty!”

So, Verheugen seeks out large models to paint, and he calls his paintings of them “anti-rexic.”

For example, for years he had seen a woman who worked in his neighborhood boulangerie – she was large, but with a certain “allure.” She agreed to pose nude for Verheugen. When discussing that painting, Verheugen talks about Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” – his famous work illustrating ideal human body proportions. And when he searches for the name of the “original” large woman but cannot think of it, I proffer, “the Venus of Willendorf,” a name from Art History 101 of the tiny limestone figurine with pendulous breasts and a huge belly carved around 25,000 years ago and discovered in a Paleolithic site in Austria. When he confirms that yes, that’s the name he was searching for, I am delighted, as I have been waiting a lifetime to drop that name in conversation.

“Librement après Mondrian, à la boulangère”. Photo courtesy of the artist – Jos Verheugen

Verheugen mentioned “Vitruvian Man” because, when he painted the woman from the boulangerie into a Mondrian abstract, he realized she “fits exactly into [the painting], so she had perfect proportions,” as did Leonardo da Vinci’s man, 530 years earlier. And her stance – erect, with her elbows resting on a shelf behind her, her large stomach protruding and pendulous breasts hanging – said, “Take me as I am,” something that will be endlessly reassuring to those of us who increasingly depend on the hydraulics of a good bra.

Verheugen talks of women buying diet pills and about the “before” and “after” photos seen in magazines, in which “the before and after photos are not even of the same woman.” He tells me about a woman who told him, “I do this kind of work, but I’m always the ‘before’ photo.”

“I always prefer the one before,” he adds. It’s easy to understand why he hates Victoria’s Secret for what it does to real women.

“This is my mission,” he reiterates. “To show ‘real’ women who are alive.”

Verheugen’s desire “to promote body positivity,” and his work and attitude, can be even more appreciated by viewing it in a larger context, as it is a subject of interest to both the popular press and scientific journals. A quick internet search of “articles about body image” reveals nearly 1.4 billion results, with titles such as “How Social Media Is a Toxic Mirror,” and “Social Media, Thin-Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes: An Exploratory Analysis.” A search of “articles about body shaming” reveals nearly 4.8 million results, with titles such as “How social media is increasing a person’s exposure to body shaming and body image,” and “Negative affects that Social Media causes on Body Imaging.” New York Magazine’s archives of internet articles about body shaming includes this title: “King Tut Is a Victim of Body Shame – Posthumously.” Talk about reductio ad absurdum.

While in 2015, it might have been inconceivable that Vogue would put a large woman on its cover, it has in fact done so this very month. And not only large, but black. Gracing the cover of the October 2020 Vogue magazine is Lizzo, an American singer, rapper, songwriter, and flutist, and a 2020 Grammy winner who also happens to reportedly weigh even more than Lucien Freud’s Big Sue. She had already posed nude for the cover of an album she released in 2019, wearing nothing but a 42-inch wig.

When she was chosen, she called herself the first “big black woman” on a Vogue cover. She once said, “Girls with back fat, girls with bellies that hang, girls with thighs that aren’t separated, that overlap. Girls with stretch marks. You know, girls who are in the 18-plus club. They need to be benefiting from…the mainstream effect of body positivity now.” Even on the covers that depict her, however, there is not a wrinkle or telltale bit of cellulite to be seen.

But Verheugen keeps it real. While he was influenced by Dutch painters Kees van Dongen and Charley Toorop – he feels the importance of the Dutch tradition – he created his own style, which he calls “expressive naturalism”; that is, his paintings are figurative, but not realistic or hyperrealist. What you see in reality is pretty much what you will see on the canvas, with whatever would be the artistic equivalent of a writer’s dramatization needed to make it art: large, shapely women with ample hips and breasts, and all the sags and cellulite that might make some people cringe, but are apparently perfectly attractive to others. Slim women are of no interest to Verheugen as models. He paints what he likes to see, and he likes to see big, fleshy women.

And, as Verheugen explains, “The bigger the woman, the more she is going to break the lines of Mondrian, in that the lines are going to follow her body.”

“Librement après Mondrian, with cassowary family”. Photo courtesy of the artist – Jos Verheugen

Verheugen also talks about the need to sometimes “read” a painting. He is talking, specifically, about the painting in his studio of a cassowary, a cousin of the emus, and its chick. It is the male cassowary that incubates the eggs, and once hatched, it is the male that raises the chicks. This is a metaphor, if you will, for the relationship between Verheugen and his daughter, Ella, so in that respect the painting is autobiographical. Cassowaries are known for their viciousness when they need to protect themselves or their chicks, and you get the impression that that, too, is a metaphor for how protective Verheugen is of his daughter.

Verheugen does a portrait of Ella every year around her birthday, as he does of himself. “It’s a moment for reflection and experiment. Over the years, the project depicts the continuous evolution of life, state of mind, painting technique and artistic approaches.” This year, for Ella’s 18th birthday, he painted a group portrait of her with several friends.

“Jos & Ella (father & daughter) version 48/8 years old”. Photo courtesy of the artist – Jos Verheugen

“I think about art every minute of the day,” Verheugen says, and when you talk with him, you realize his brain is brimming with endless knowledge and ideas, and a great enthusiasm for his métier. He looks into, not just at. Clearly, he has reflected mightily on societies and their mores, and like any good artist, he is impatient with them and questions the received wisdom and wants to smash paradigms.

Verheugen’s atelier, at 22 rue Barrault in the 13th arrondissement, is hidden away among other bungalows built atop a roof in an agreement with the city of Paris in the early 20th century to allow a hotel to be built if living spaces were created for the people who would be displaced. He calls his atelier “my second skin.”

Verheugen does commissioned works, and you can visit his studio by appointment. His next exhibitions will be February 5–7, 2021, at the EuropArtFair, Westergasfabriek, in Amsterdam; and February 9–14, 2021, at the Salon Comparaisons, “Art Capital” at the XXX Grand Palais, Champs de Mars, in the Paris 7th.

Internet and contact information for Verheugen are as follows:

Jos Verheugen

22 rue Barrault, 75013 Paris, France

[email protected]

Mobile: +33 (0) 6 2651 4770

Fixed: +33 (0)1 45 89 08 46

www.josverheugen.com

www.facebook.com/jos.verheugen.3

Lead photo credit : Paris-based artist Jos Verheugen in his studio with detail of painting from his “Librement après Mondrian” series / photo by Diane Stamm.

More in artists in Paris