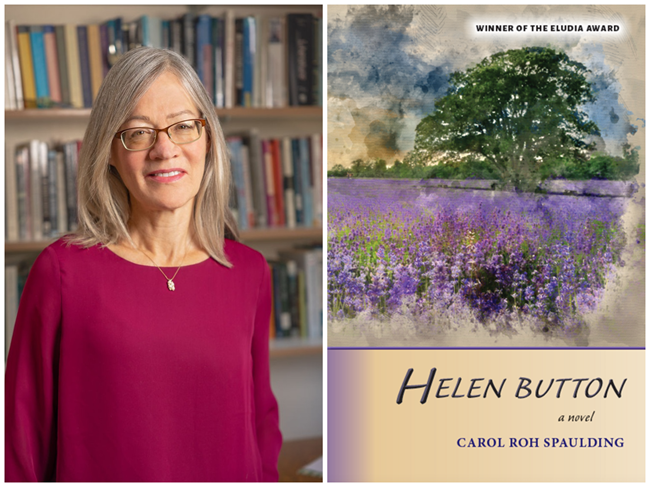

Interview with Author Carol Roh Spaulding

Carol Roh Spaulding is a professor of literature at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. Her latest novel, Helen Button, takes a minor character from Gertrude Stein’s 1940 book Paris France, and imagines a whole life for this character — Hélène — that follows her from her childhood in rural France in the 1930s, to her life in the United States in 2005. Through Hélène’s life experiences, and her reflections upon them, readers are challenged to think about the ravages of war, and grapple with thorny questions about individual responsibility in the face of injustice. Professor Spaulding recently took the time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions about Helen Button for Bonjour Paris.

What inspired you to write this book? Did you have a sudden moment of epiphany, or was it an idea that grew over time?

In the 1980s, I lived in Paris at 26 rue de Fleurus, the former residence of Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas. I dreamed of being a writer, and I later went to graduate school in American literature, and read and learned more about Stein. (Decades later, I wrote a nonfiction piece for Brevity about that time in my life, which I later made into a three-minute film viewable here and below.) If you’ve ever lived in Paris, there’s so much you want to capture and keep in your memory. It really is “a moveable feast,” as Hemingway called it. Many details of my time on rue de Fleurus found their way into the novel. There was no sudden epiphany, but probably the biggest influence was Janet Malcom’s biography of Stein and Toklas, Two Lives. It investigates the question many have wondered about, but few took the time to answer: what were two Jewish, lesbian, American women doing in Vichy-controlled France during World War II?

When I read novels that draw on real-life historical events, I am always curious as to which parts are historical and which parts were invented by the author. Can you give readers a general idea of what the historical background of this story is? Which are the actual historical events and people that are key to the plot? And how did you use your imagination to fill in some of the blanks?

The novel is structured using a dual time narrative that moves primarily between World War II and the year 2005, when the Paris banlieues erupted after the death of two Algerian boys in a tragic accident. A significant background narrative that informs the novel is the atrocity that took place in April 1944 at the Children’s House at Izieu, where 44 Jewish children were discovered by Klaus Barbie, their caretakers slaughtered, and the children removed to Auschwitz. One child survived. These events bookend Hélène’s story as a young woman, and again as a woman near the end of her life, when children are no safer, and the scars of war no less consequential.

As a trained scholar, I enjoyed doing the academic and historical research that I got to weave into the narrative. Like many writers I know, I did almost too much research and had to cut passages I loved and wanted to make use of that didn’t ultimately belong in the story. The verisimilitude of a scene and its sensory and emotional accuracy depend on the smallest details, such as the term “Canada,” which was used during the Occupation for items obtained through the black market that had been stolen from Jewish people. The result of my research for fiction is always part historical detail, part imaginative bridging. My favorite research was the opportunity to spend several days with Stein’s papers and items housed at Yale’s Beinecke Library. There’s nothing like working with primary materials to fire a writer’s imagination.

Classroom at the Maison d’Izieu. Photo credit: Benoît Prieur / Wikimedia commons

What sources did you use for the parts that are historical–especially regarding the lives and activities of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas during World War II?

I sought to understand how and why Stein and Toklas remained in France during World War II, how Gertrude’s writing centered daily life for the author and her devoted assistant, and what daily life must have been like during the war despite the danger and hardship they endured. In addition to this list of titles that informed the narrative, I read dozens of articles about Stein’s literary history, the Children’s House at Izieu, pediatric hospice, the relationship between France and Algeria, the year 1968, the Clichy-sous-Bois incident of 2005, and much more.

- Bruce Kellner, ed. A Gertrude Stein Companion, Greenwood Press (1988)

- Serge Klarsfeld, The Children of Izieu, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. (1984)

- Janet Malcom, Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice, Yale UP (2008)

- Chris Raschka, The Purple Balloon, Schwarz and Wade, (2007)

- Leila Sebar The Green Chinese of Africa, Roman/Stock (1984)

- Gertrude Stein, Paris, France. Liveright London (1940, 1970)

- Gertrude Stein, “Reflection on the Atomic Bomb” (1945)

- Gertrude Stein, Stanzas in Meditation, the Corrected Edition, ed. By Suzanne Hollister and Emily Setina Yale UP (1956, 2010)

- Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons, Project Gutenberg, (1914)

- Gertrude Stein, The First Reader, Maurice Fridberg, London (1946)

- Gertrude Stein, The World is Round, illus. by Clement Hurd, (1939)

- Gertrude Stein, Wars I Have Seen, BT Batsford Ltd, (1945)

- Margaret Collins Weitz, Sisters in the Resistance: How Women Fought to Free France, 1940-1945, Wiley (1998)

- Barbara Will, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Fay and the Vichy Dilemma, Colombia UP (2011)

- Brenda Wineapple Sister Brother: Gertrude and Leo Stein Nebraska UP (1996)

Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein on the Terrace at Bilignin, June 13, 1934/ by Carl Van Vechten/ New York Public Library/Public Domain

What were the greatest challenges in writing this very ambitious book? Technically? Emotionally?

Some of the most magical and artistically fulfilling times of my life were spent researching and writing this novel. The greatest challenge was simply persistence – fitting it in around the edges of my family obligations and professional life. Once or twice a year for many years, I got to spend a week at a nearby retreat center, where I would write furiously, sometimes 16 hours a day, stopping only for quick breaks. The idea for a dual timeline narrative came very late, and once I decided on that solution, I could see the parallels I wanted to make and the narrative came together easier.

I sense ambivalence in your view of/feelings about Gertrude Stein. I’m guessing that you, as a professor of literature, admire her as a writer; but also that you have reservations about her as a person. I’m making these assumptions on the basis of the story you tell in Helen Button, which of course is fiction. But I can’t help asking the question anyway! Can you comment on this? That is, on your own personal view(s) of Gertrude Stein?

My early view of Stein was formed by the 1987 film made by Jill Godmilow, called Waiting For The Moon. I was enchanted by the way Stein championed other writers and artists. It was the first time I had seen depicted the life of a serious woman artist who lived with independence, courage and imagination. I’d never thought of Stein as an ambivalent figure until I read Malcom’s Two Lives. Once I began my research, I learned that many authors felt ambivalent about her later in her life.

Portrait of Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso, 1906

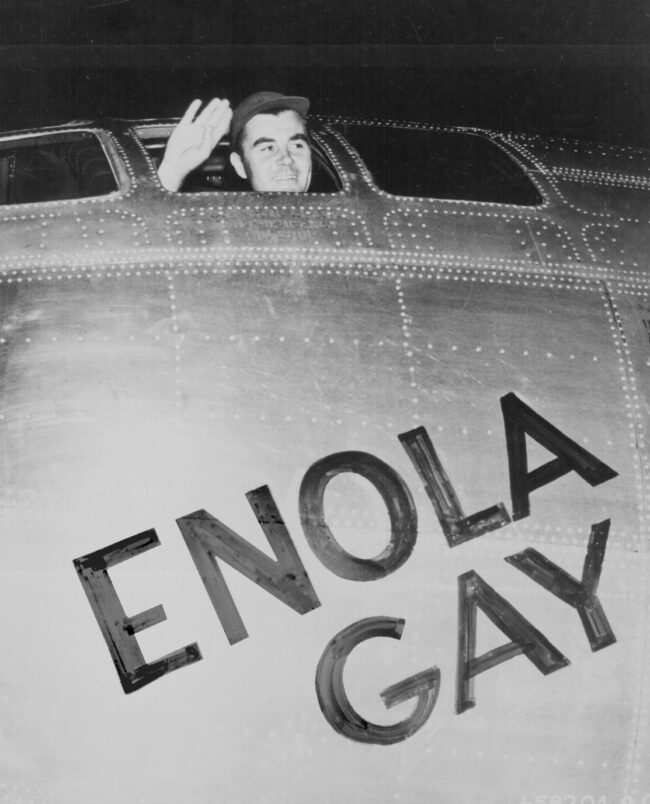

There is one very brief reference to a character who appears only once in this book, and who is (seemingly) unrelated to most of the rest of the story. His name is Paul Tibbets and he is a historical figure. Why did you decide to include him?

Stein is said to have had an unusual response to the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 5, 1945. Rather than ponder the destruction of entire populations with a single act, Stein’s public statement suggested a detached and perfunctory viewpoint incommensurate with the scale of destruction. Her defenders claim that was precisely the point: what possible response could speak to such an unfathomable act? In Helen Button, Hélène’s response is intended to be seen as a contrast to Stein’s. By this time in the war, Hélène had witnessed more than one quizzical response from Stein regarding world events. Hélène’s own response was to ponder what sort of man would have been capable of executing an order like this on a peaceful summer morning late in the war. Hence, I included the actual historical figure who dropped that bomb — his name was Paul Tibbets. He was the pilot of the Enola Gay, a bomber plane named after his own mother.

Paul Tibbets waving from Enola Gay’s cockpit before taking off for the bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. Photo: 509th photographer Pfc. Armen Shamlian/ Public domain

I love the way you have set your novel in two historical periods — France in the lead-up to World War II, and during the Nazi Occupation; and Paris in 2005. What is the connection between these two times in France, if any?

I promised myself that if I ever had the opportunity to write about my time in Paris, I would include what I truly felt and saw, even if that ran counter to Americans’ often romantic expectations. In graduate school, I took a course in French literature and chose to study the literature of the beur. It opened my eyes to the experience of Algerian post-colonial immigrants in contemporary France. Particularly, a novel by a woman named Leila Sebar helped me understand the concept of statelessness experienced by Franco-Algerian youth. Eventually, I saw the opportunity to describe a parallel between how Jewish children were treated during World War II, and how Arab children have been treated since Algerian independence, and up to the present day. In 2005, Arab children are not singled out and sent to die in concentration camps; but many live sequestered in the banlieues, and grow up in profound impoverishment. Hélène has lived long enough to have served as a witness to both kinds of injustice.

Author Carol Roh Spaulding

How did you get the material you needed for the scenes in Clichy-sous Bois?

Since I left France in the late 1980s, uprisings such as the one in Clichy-sous-Bois have happened every five to 10 years. I have always followed the coverage. The banlieues of Paris still experience massive inequity, and Arab and Muslim populations still exist in uneasy tension – perhaps now more than ever – with the rest of France. I have never been to Clichy-sous-Bois, but I have read about how there is no civic will even to make public transportation more straight-forward, even though many who live in the banlieues are the underclass who work in Paris every day.

You have dedicated your book to “the children of war.” Do you want to say a word about why you did that?

My dedication is related to the novel’s epigraph, by Stein. (“In time of war, you know much more what children feel than in time of peace, not that children feel more but you have to know more about what they feel.”) In her somewhat indirect way Stein reminds us that we must acknowledge children’s emotional experience of war. Her biography, of course, doesn’t bear that out. In fact, a careless remark by Stein may have doomed one Jewish child to death. So, her declaration is ironic. My dedication is meant to highlight that irony, and to acknowledge that the casualties children suffer in wartime are a profound blow to our humanity.

Maison des enfants d’Izieu, today a museum and memorial dedicated to the Jewish children deported to Nazi concentration camps. Photo credit: Chabe01 / Wikimedia commons

What’s next for you? Is there a new novel in the works?

Yes, something very different. I’m researching the real-life story of an Iowa State Penitentiary inmate from the 1970s whose connection to my husband’s family caused profound generational trauma.

What is the main takeaway you would like your readers to come away with, after reading Helen Button?

People in the “free zone” of France made a bargain. They gave up their country to keep their way of life. They were not evil, and they were not unique. At most moments in history, including this one, tending one’s own garden, as it were, is simply not enough. Humanity is calling.