Holocaust Remembrance Day: Remembering the Children of Izieu

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

As Holocaust Remembrance Day approaches, I find myself remembering again the haunting exhibition called “You will remember me,” which I saw last year at the Museum of the Art and History of Judaism in the 3rd arrondissement. It told the story of 105 Jewish children who found refuge at the Maison d’Izieu, about an hour’s drive from Lyon, in 1943 and 1944. Among the photos and documents were displays of writings and drawings, many of them left behind by children who were later murdered in the concentration camps.

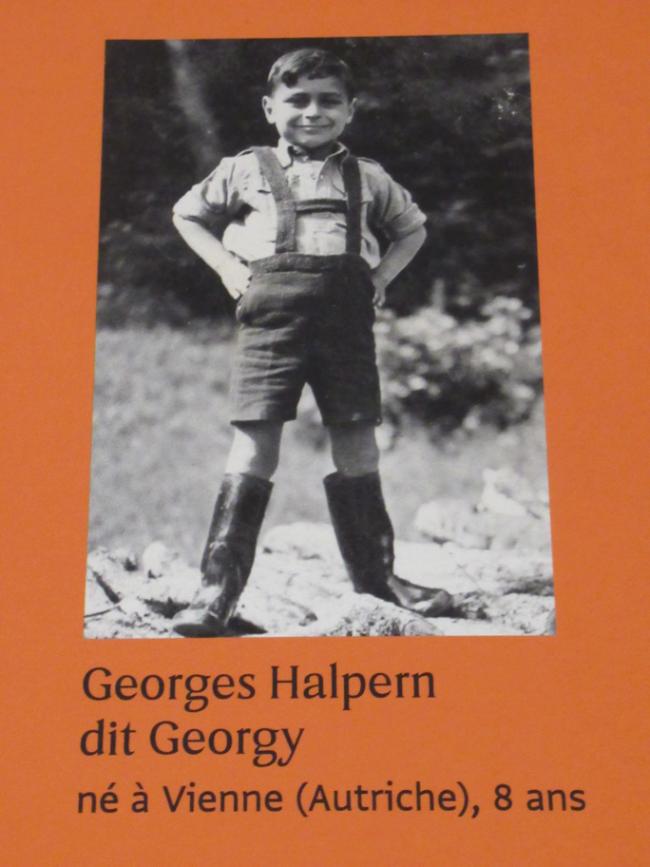

One of the photos showed Georges Halpern, known as Georgy, aged 8, in dungaree shorts and over-large Wellington boots, staring confidently at the camera with his hands on his hips. He seemed to have paused from his gardening tasks, perhaps in the vegetable garden at Izieu, where the children were encouraged to help. Many of them had lost contact with their parents, but Georgy was able to correspond with his mother. In one letter he thanked her for the little parcel she’d sent, containing socks, a coloring book, apples and some honey, asked her to send him a copy of his favorite magazine and signed off with the words “I kiss you with all my heart.” One letter at least came back marked “Return to Sender.”

Georges Halpern, “You will remember me” exhibit. Photo Credit: Marian Jones

Georgy wrote this letter from the Villa Anne-Marie, a remote house on the edge of the little village of Izieu, where a remarkable Jewish couple with Russian/Polish heritage provided sanctuary for children who’d been separated from their parents, some of them rescued from nearby internment camps. Marin and Sabine Zlatin had resolved, despite the enormous dangers they faced in Nazi occupied France, to provide as normal a life as possible for the children. They varied in age from 3 to 16 and it was hoped that they would eventually be placed in families or returned to their relatives.

On April 6th, 1944, came horror. On the orders of Klaus Barbie, two lorries were sent to the Maison d’Izieu at 8 o’clock in the morning and SS officers rounded up everyone they found. The 44 children and 7 adults taken were deported to Auschwitz and other camps. Only one – one of the helpers – survived. Sabine Zlatin, who understood what danger they were all in, was away that day, trying to organize dispersing the children and sending them elsewhere in the hope of saving them. Her intention had been for that to happen later that same month.

Maison des enfants d’Izieu, today a museum and memorial dedicated to the Jewish children deported to Nazi concentration camps. Photo credit: Chabe01 / Wikimedia commons

Much of what we know about life at Izieu shows how well the children were looked after. Conditions were difficult – the only water came from an outside fountain, for example – but a routine was established to keep life as normal as possible. There were lessons every day – math and writing in the mornings, grammar and reading in the afternoons – the children helped a little with domestic tasks and went on walks and bike rides along the River Rhône where Georgy told his mother he was learning to swim.

Classroom at the Maison d’Izieu. Photo credit: Benoît Prieur / Wikimedia commons

A combination of rationing and the need for secrecy must have made finding enough food difficult, but they did what they could with the vegetable garden and produce from local farms. One child, Samuel Pintel, who survived because he had left Izieu before the Germans arrived, wrote much later, as an adult: “I can still smell the cabbage soup, served in the evenings and see the sumptuous Sunday lunch of black pudding and mashed potato and the big slices of bread and chocolate we had in the afternoons.” You can only marvel at the resourcefulness of the staff and it’s some comfort to read a comment by Gabrielle Perrier, a trainee teacher at Izieu, who survived because she happened to have a day off on April 6th, that mealtimes were “joyous and noisy.”

Another reason to hope that the children found a brief happiness at Izieu comes from learning about the drama and singing activities which Sabine organized and the way the children were encouraged to draw, make cards and celebrate special events. Details it’s hard to get out of my mind include plans for New Year’s Eve, including hand-drawn cards labelled “Bonne Année,” and colored pictures of farmyard scenes, Puss in Boots and American Indians. The children made “films” – Captain Blood’s Treasure and Chasing a Robber – by drawing a series of pictures and glueing them into long sequences to be shown “magic lantern” style while a narrator read out the story they had written.

I tried to imagine the adults, so resolute in the face of danger and so pressed by the sheer enormity of their task, who found the humanity to nurture these children. Marin and Sabine Zlatin knew they were risking everything to try and keep their charges from the Nazis, but they ran a home where laughter was encouraged. Marin was shot by the SS in July 1944. Sabine left for Paris where she helped organize the reception for survivors from the concentration camps which was centered on the Hotel Lutetia. Forty-three years later she attended every single day of Klaus Barbie’s trial and gave a moving testimony.

As for the children, every new detail I came across was heart-rending. There were so many cards and letters. Jacques Mathieu-Dauder wrote to ask his mother if she could send him some stamps for his collection: “That would make me very happy because I could swap them for others.” Max Tetelbaum, 12, who was from Belgium, wrote a card to his younger brother Herman on his 10th birthday. Alice-Jacqueline Luzgart wrote to her mother, listing her friends – Mina, Paulette, Marthe, Suzanne, Liliane – telling her that at night they lay talking about films and “about our mothers. I often talk about you.”

Samuel Pintel described the reassuring normality of the lessons the children were given. “When I arrived at the seat I’d been allocated, I found an exercise book, with the work I had to do written out at the top of the page or some sums to do, all in red ink in beautiful handwriting. The staff found time, despite all the other things they had to do, to prepare lessons for every child every morning. That alone is astounding, yet they injected a little frivolity too, as Samuel described: “I learned to fold paper to make aeroplanes and sailing boats.”

Aerial view of the Maison d’Izieu. Photo credit: Benoît Prieur / Wikimedia commons

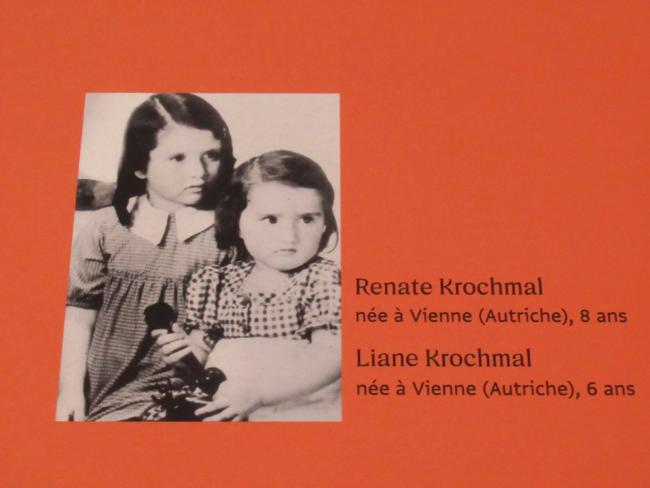

But of course the trauma was under the surface all the time. One helper remembered Émile, the child who “took the longest to settle at night.” He was, she recalled, “a little blond boy, with very blue eyes … he was sweet, adorable, but he was traumatized because he had seen his parents being arrested.” The photos of so many of the children gazed out from the walls of the exhibition. Parisian children like Mina Halaunbrenner, 8 and her little sister Claudine, 5, and two brothers, Henri and Joseph Goldberg, aged 13 and 12. Senta Spiegel, 9, born in Vienna, her dark hair clipped back to reveal a mischievous smile. Renate and Liane Krochmal, 8 and 6, in contrasting gingham smocks. Ten-year-old Claude Levan Reifman, looking so confidently straight at the camera. And so many more.

Is the tragic story of the children of Izieu at all relieved by knowing that they found some happiness there? Paul Niedermann, a child who was at Izieu for a little while before he left for safety in Switzerland, recalled later that “for me, the house at Izieu was like a haven of peace, because we were so far from the rest of the world.” He became a writer and photographer, and in later life told his story many times in public. (He lived until he was 91.) Reminders of the darkest things that humans can do to one another must surely be told and retold. We like to think this is in the past and couldn’t happen now. But as Paul Niedermann explained, the children of Izieu also thought it couldn’t happen: “We told ourselves that the Germans wouldn’t come and find us here. You couldn’t imagine it was possible.”

Lead photo credit : "You will remember me" exhibition poster. Photo Credit: Marian Jones

More in history, holocaust, Holocaust Remembrance Day, Maison d’Izieu, Remembrance

REPLY