Sarah Bernhardt, the Artist

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Sarah Bernhardt, 1844-1923, was the greatest actress of the 19th century. She was the theater’s Meryl Streep backed with a publicity machine rivaling Madonna’s. She was in fact a primadonna, the first lady of the stage. With her sold-out performances, every major playwright longed to write for her. Provocatively nicknamed the “8th Wonder of the World”, emperors took a knee before her; aristocrats gave her jewels. She was ruthlessly ambitious, with an entourage of fans, friends and lovers trailing her every move. Bernhardt had a taste for the bizarre. She lived among a menagerie of wild animals and circulated a photo of herself sleeping in a satin-lined coffin. Although known for her emotional stage presence, Sarah Bernhardt is lesser known for her artwork, which as equally outstanding.

Young Girl and Death by Sarah Bernhardt. (C) the Wellcome Collection

In 1869, the sculptor Roland Mathieu-Meusnier was commissioned to sculpt Bernhardt’s likeness. The actress peppered the sculptor with so many questions and so much constructive criticism, that he asked her why she didn’t take up sculpting herself. If Mathieu-Meusnier could be her teacher, Bernhardt enthusiastically said yes. That evening she ran home and shook her sleepy aunt awake to sculpt her image into a medallion, which she proudly showed her mentor the next day.

Mathieu-Meusnier was a popular sculptor who specialized in allegory and monument work. He thought that Bernhardt’s sensuous hands and long tapering fingers were intended to “caress works of art.” Like her teacher, Sarah also produced academic, allegorical works. She devoted every spare moment to studying and practicing the art. Her progress was remarkably rapid and she was highly successful at sculpting.

Bernhardt had a pedestrian taste in art. She was active in Paris at the heyday of the Impressionists yet had no interest in their paintings; instead, she liked the pretty postcard images by her close friend Louise Abbéma. Georges Clairin, who fawningly painted Bernhardt in flattering poses, was also a fixture in Sarah Bernhardt’s ‘court.’

Like nobility, Bernhardt was driven every morning by horse and carriage to her studio at 11 Boulevard de Clichy. In the interior of her Pigalle studio, Bernhardt created a bohemian atmosphere. Her large studio was a mismatched jumble of objets d’art. Abbéma and Clairin painted murals in her foyer, dining room and bedroom ceiling depicting roles she had played on the stage.

Bust of Victorien Sardou by Sarah Bernhardt (C) Wikimedia Commons

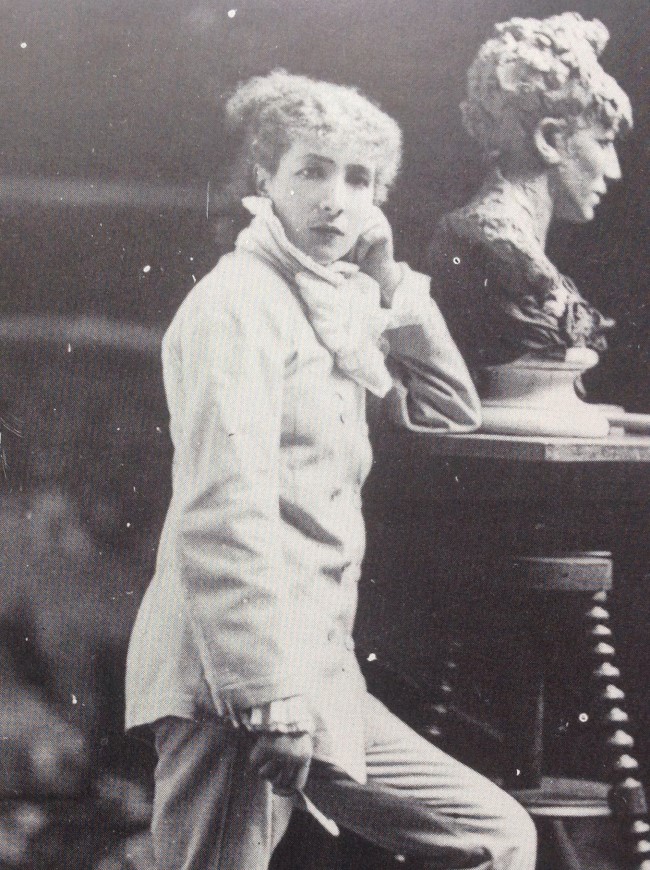

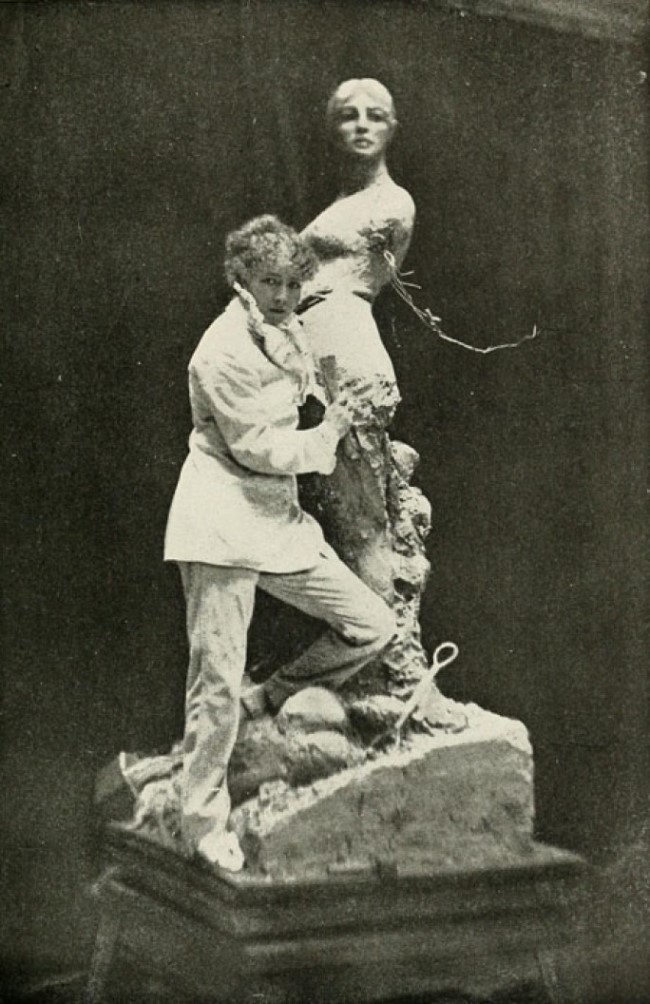

The costume she received visitors in was very much like Watteau’s Pierrot Jules; an all-white satin trouser suit with a massive ruff of white tulle at her neck. She said – but it is questionable – that in these “boys’ clothes,” she perched on a ladder and dabbled all day with clay. Nineteenth- century celebrity interviewer Sarah Tooley from Women at Home magazine said there was little evidence, except for some plaster dust, that the space was used as a studio. Yet other visitors to her studio confronted many statues in various states of completion. Painter Walford Graham Robertson reminisced that he helped Bernhardt destroy a work in progress, turning a half-finished work into a pile of mud. Her large studio would one day be Picasso’s.

In 1874 Sarah Bernhardt’s theater company, the Comédie-Française, forced her to take a health break, fearing she had tuberculosis. However, taken from her own words, the Comédie-Française began to affect her nerves. They wouldn’t give her the roles she thought she deserved. With so much time on her hands, Bernhardt threw herself into sculpting with frantic enthusiasm, working in clay which she had cast into bronze, and marble which is inexplicably well-done.

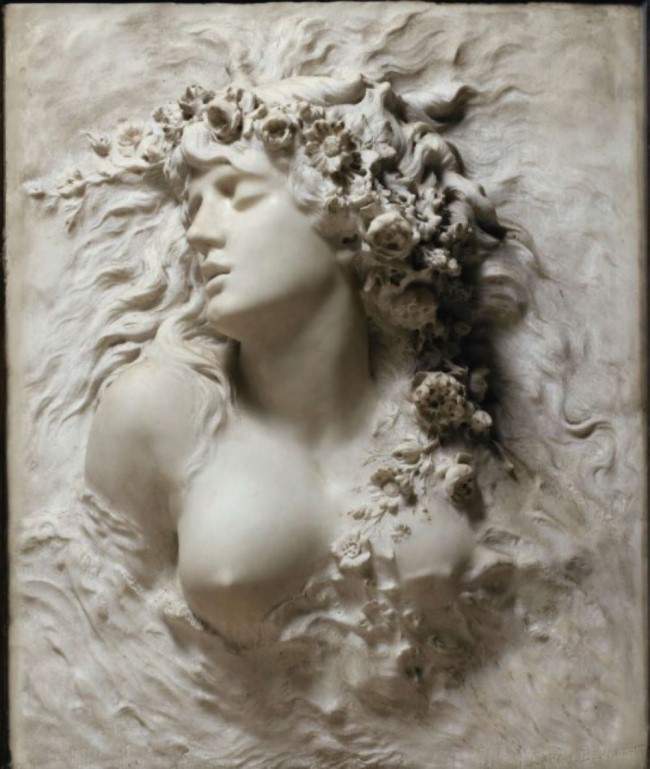

Sarah Bernhardt, Après la tempête (After the Storm), ca. 1876; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC. (C) NMWA

In 1875 she exhibited the marble bust of her younger sister, completed jus five months after her death. An early composition titled Après la Tempête, which she exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1876 won an honorable mention. A bereaved woman she’d seen at the Brittany coast grieving for her drowned grandson inspired the Pieta-like group. For an early piece la Tempête really is remarkable. When working on the sculpture, Sarah Tooley said that Bernhardt visited the dissection labs at the Paris School of Medicine.

Author Pierre Veron made the first mention of Après la Tempête in the account of his visit to Bernhardt’s studio in 1876. The playwright saw Bernhardt “battling away with the group… grabbing a modeling tool… digging her dainty little hands into a big pile of clay.”

Artist Alfred Stevens urged Bernhardt take up painting. She thought his idea an excellent one and in her free time she went on sketching trips with her favorites, Georges Clairin and Gustave Doré. Sketches she made of her roles in the theater were very well rendered and included scenes from Adrienne Lecouvrier, Le Sphinx, Frou Frou, Hernani, and Phedre. She exhibited a two-meter long canvas, La Jeune Fille et le Mort, at the 1878 Salon which was subsequently engraved for the Salon catalogue.

Louise Abbéma by Sarah Bernhardt. At the Musée d’Orsay. Photo by Hazel Smith in 2018

In June 1879, only 18 months had passed since Bernhardt took up her paint brushes. While her theater company was in England, Henry Jarrett, her agent extraordinaire, arranged an exhibition of eight of Sarah’s sculptures and 16 of her paintings at the fashionable gallery of Thomas Roberts and Son’s at 33 Piccadilly Circus.

The opening was spectacular. Invitations were sent to 100 aristocrats and celebrities, but in Bernhardt’s own words over 1,200 showed up. The exhibition was sponsored by the then Prince of Wales, Edward. Prime Minister Gladstone engaged Sarah in conversation. Artist Frederic Leighton complimented Sarah on her painting Marchand de Palmes, which Prince Leopold purchased. In total 10 paintings sold and six sculptures, including a smaller bronze reproduction of Après la Tempête, to an unspecified Lady Ethel H. for £400.

Bust of Ophelia by Sarah Bernhardt. (C) Sotheby’s

The exhibition of Bernhardt’s works was enthusiastically written up in the society pages. She was aware her famous signature helped her sell her works. She simply wanted to raise money for two lion cubs on offer to her in Liverpool. Sarah came away with a cheetah, a wolf and several chameleons instead.

Rodin called Sarah’s work “old fashioned tripe,” at the same time his own work was criticized as being “immoral modernism.” The press took umbrage that a leading Comédie-Française actress would exhibit her artwork. Emile Zola, trusted friend to artists, defended her, saying, “She is reproached for not having stuck straight to dramatic art… Not content in finding her too thin or declaring her mad, they want to regulate her daily activities.” Zola also stated ironically that, “perhaps a law should be passed to prevent a plurality of talents.” And of course, the press derided her for wearing trousers, a transgression of feminine dress codes.

Sarah Bernhardt Working on her Sculpture of Medea. (Photograph by Melandri, c. 1875). (C) Public Domain

Sarah Bernhardt’s antics caused so much gossip that it caused a permanent rift between her and the Comédie-Française. Her manager Emile Perrin asked her what she was trying to prove. He detested her caprices and eccentricities. Other actors in her troupe set a campaign against her. She wrote to Le Figaro stating that she was one of the worst paid members of the Comédie-Française. Whether or not that was an accurate statement, she wrote another letter to Le Gaulois, stating that her art sales brought her 30,000 francs per year. “My brush and chisel will make a second existence, much calmer and profitable than the first.” She left for good in 1879. She and Perrin never spoke again.

She never gave up acting but for a span of 25 years, Bernhardt exhibited at the Paris Salon. Fifty sculptures have been identified through contemporary accounts and photographs. The location of 25 have been found. Mrs. Tooley’s writings have been the source of many.

Bernhardt’s Medea of 1875 was a powerful, life-sized work. The bust of her friend Louise Abbéma (1878) is now on display at the Musée d’Orsay. Her bas-relief of Ophelia is exquisite. Bernhardt’s Figure of Music was bought by the Monte Carlo Casino.

Some of her sculptures were inspired by her work as an actress, as was her bronze Art Nouveau inkwell. Created in 1880, it is a very Goth self-portrait of Bernhardt with wings, inspired by her 1874 performance in Le Sphinx.

A painting of Sarah Bernhardt by Jules-Bastien Lepage

In 1897, she exhibited a bust of Emile de Girardin, and a bust of the vaudeville dramatist Busnach. Sarah Bernhard’s bust of playwright Victorien Sardou confirmed her talent as an artisan. Sarah Tooley wrote in Cassell’s magazine of 1899 that she visited Bernhardt in her studio hard at work with her chisel on the bust of Sardou. Bernhardt included small, skillful carvings of herself and her sister on either side of the plinth and stated “if one cannot not model one’s face correctly how should one expect to succeed with those of other people?”

Her bust of Baron Adolphe de Rothchild wasn’t as successful. Commissioned for a large sum, she worked on it from 1874-76. Biographer Cornelia Otis Skinner recounts in her 1967 book Madame Sarah, that de Rothschild yowled, “This is supposed to be me?” and tore up the substantial cheque he had in hand. Sarah responded by smashing the piece to the ground. In her own memoirs however, Bernhardt said that she tried to capture de Rothschild’s likeness three times and finally gave up, leaving him to bow coldly to her when they crossed paths.

Although Sarah Bernhardt posed confidently alongside her works with chisel in hand, she was vulnerable to skepticism about her talent and commitment and had been accused of passing other people’s work off as her own.

Original Sketch by Sarah Bernhardt included in Souvenir & Catalogue: Mlle Sarah Bernhardt’s Art Exhibition 1880.

Après la Tempête, at the 1876 Salon, met with both acclaim and doubt, which she related in her 1907 autobiography: “Is there any need to say that I was accused of having got someone else to make this group for me?”

It is rather hard to believe that one of Bernhardt’s first forays into sculpting could produce such an amazing and well-received work. Could Mathieu-Meusnier be the actual artist? Doctoral theses written on the subject contest whether Bernhardt did her own carving.

“Encrier Fantastique,” bronze self-portrait as a sphinx, by Sarah Bernhardt. (C) Christies

Although Bernhardt stated in her autobiography regarding the reduced marble version of Après la Tempête, that she “had worked at it with the greatest care,” it has been suggested that she had a practicien – an experienced carver – to rough out the sculpture’s basic shape and that some finishing work was done the same type of craftsman. The full extent of Bernhardt’s marble carving isn’t really known.

Sarah Bernhardt could turn her hand to almost anything – acting, music, sculpting and painting. She was an artist in all that she did. She successfully fought against the press and detractors who treated Bernhardt as a “tall poppy” that needed to be mowed down before it could reach the sun.

Lead photo credit : Sarah Bernhardt in the studio with her self-image bust (C) Wikimedia commons

More in artists in Paris, exhibition, Sarah Bernhardt

REPLY