To Capture What We Cannot Keep: An Interview with Author Beatrice Colin

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

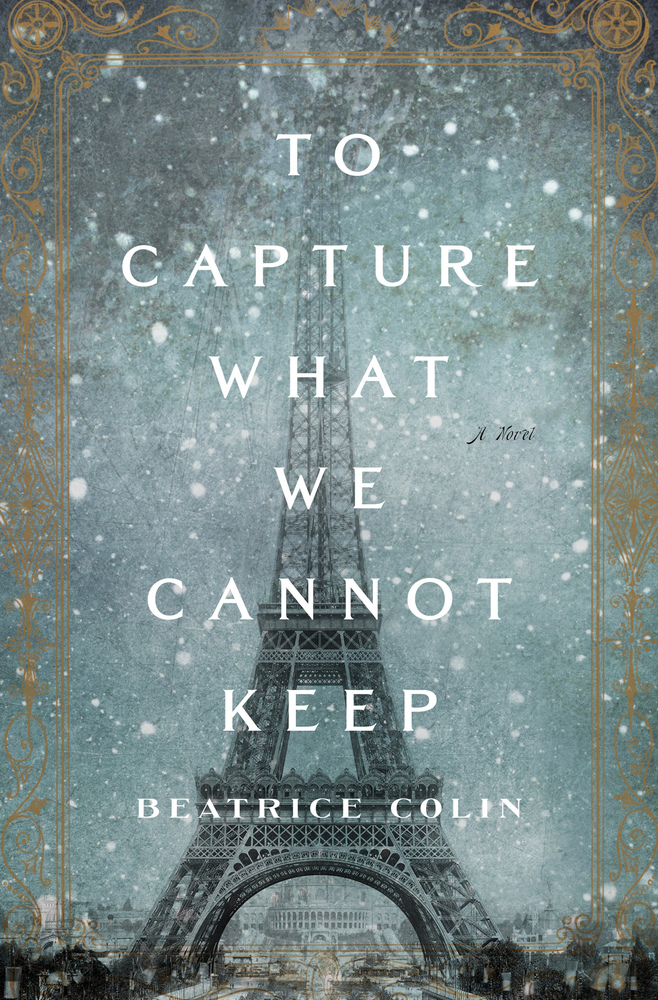

Fill in your credentials below.

To Capture What We Cannot Keep

Beatrice Colin is a former arts and features journalist, and the author of seven novels, five for adults and two for children. She also writes short stories and radio plays for the BBC. Her latest novel, To Capture What We Cannot Keep, is set mostly in Paris during the time of the construction of the Eiffel Tower, with scenes in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and West Africa as well. The novel follows the slowly evolving relationship between a young Scottish widow and a French engineer who, despite the constraints of class and wealth, fall in love. The Library Journal gave it a starred view, noting, “this exquisitely written, shadowy historical novel will appeal to a wide variety of readers, including fans of the Belle Epoque.” Booklist said, “Colin’s Paris is a city of painters, eccentrics, aristocrats, desperate prostitutes, secret lovers, and the magnificent artistic vision taking shape high above them.” Colin was born in London, raised in Scotland, and lived for a few years in Brooklyn, New York. She now lives in Glasgow, where she teaches Creative Writing at the University of Strathclyde. She recently took the time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions (via email), for Bonjour Paris.

Janet Hulstrand: I’ll start with perhaps the most obvious question. You’ve written novels set in Weimar Germany, and in New York City in the early part of the twentieth century. How and why did you choose to tell this story, set in Paris–and in Glasgow–in the late 1800s? And what is most interesting about this period of history for you?

Beatrice Colin: I was in Paris on holiday–it’s a city I know and love–when I noticed the Eiffel Tower in a way I hadn’t before. I had always avoided it, as there are so many tourists and tour buses there. But I suddenly realized that I had no idea who built it and why. I looked it up when I got home and found an amazing story that I thought I could use as the spine for a novel. My two most recent books involve war in some way and so I wanted to write something different, a novel with a softer focus; on art, architecture, fashion and culture. In this novel I also include the city I live in—Glasgow—which is so often used as a backdrop for gritty crime. Remnants of a more glorious Victorian age, however, still exist, and there is some wonderful architecture here.

I usually start by finding a story I want to tell or use in some way. The tower symbolized change. It was the tallest building in the world for decades, and was made of a material—steel—that was usually used for building bridges. While much was in a state of flux—the art world for example–I liked the way that so much about France in that time was steeped in rigid tradition. It was this conflict, the old versus the new, that I was interested in exploring.

JH: How much of what we read in this novel is historical, and how much fiction? For example, Gustave Eiffel plays kind of a secondary role in this novel, to Emile Nouguier, one of the principal engineers of the Eiffel Tower. How much of Emile Nouguier’s story, as told in this book, is historically accurate, and how much is pure fiction? Also, what was the most surprising thing you learned about the construction of the Eiffel Tower in the course of writing this book?

BC: The material about Eiffel is pretty accurate. He was a determined engineer with a talent for self-promotion. I grew to admire him, and felt sorry that he became involved in the ill-fated Panama Canal scheme that nearly ruined him. Emile Nouguier is also based on a real person, but there is far less archive material on him. I had a few photographs, and knew that he never married, that he left Eiffel’s company to form his own, and that he was involved in the construction of a bridge in Senegal. His photograph captures a handsome, serious man who looks as if his mind is elsewhere. I made up his background, his mother, and the glass factory that they own. I liked the visual connection between the hot air balloon and the blowing of glass, although I’m not sure a reader would pick that up.

I think the most surprising thing about the tower is what an incredible feat of engineering it is. Every single piece was hand-fashioned and then bolted into place. I knew nothing about engineering before I started researching the book, but now I have a lot of respect for civil engineers, especially of the 19th century.

Constructure of the Eiffel Tower, 1888

JH: One of the things that really impressed me about “To Capture What We Cannot Keep” is the amazing amount of research you must have had to do to render it accurately. Not just the details of the building of the Eiffel Tower, which was all really interesting of course. But also other things, for example the care you took to describe Cait Wallace’s clothing–the confining, constricting garments that women of the period wore, and how it must have felt to be in them, how long it took to get into and out of them. How did you do it? And how long did it take you to write this book?

BC: I spent time looking at women’s clothes from the period in museums, and online, not just the top layer but the underwear too—how many layers they wore, and how they worked together. As a student I once worked in a costume museum, and found it fascinating. I have never actually worn period costume, but I could imagine how it must have felt—the weight, the discomfort. I love doing research, and I read a lot of books and looked at a lot of photographs. As a former journalist I have to get the details right, so I have to check everything I can, using whatever respectable source I can find. I also visited Paris many times—a perk! It took about five years from my first notes to publication, and went through quite a few drafts.

JH: I read in an article about you that you wrote your dissertation on the possibilities that historical fiction offers, to “look at the past through the eyes of those who are marginalized, who…run the risk of being ignored when the history of their times gets written up.” Can you tell us a little bit more about your dissertation? And also, how you tried to use the story you tell in “To Capture What We Cannot Keep” to give voice to some of those people, whose voices might otherwise never be heard?

BC: Writing fiction from a woman’s point of view, as I do, or from the point of view of an engineer, whose work usually wouldn’t be seen as interesting enough to write about, offers new ways of looking at the past. History is not just one narrative thread but many, and when you start looking you find that so much of what you think you know is only one part of the picture. I’m interested in domestic history, not the grand narratives of kings and queens, but of ordinary people. Maybe I can relate to them in a way that I can’t to Queen Victoria, for example.

JH: I think “To Capture What We Cannot Keep” would make a wonderful film. Is there any talk about such a thing happening?

BC: I would love that to happen. Fingers crossed!

Beatrice Colin

JH: When did you know you wanted to be (or perhaps when did you know that you were?) a writer? What do you love most about writing? What is the hardest part?

BC: I wrote as a child, but my first success was a short story that was chosen for a festival of new writing by young people, run by the BBC. The story was recorded and broadcast. That gave me the confidence to continue. I love writing, then editing what I’ve written to make it better. I tend to polish my work, rewording and rephrasing many times until it flows. I also love creating worlds, characters, dilemmas, images, emotions. The hardest part is carving out the time. I work as a lecturer, and although I love teaching, I find the balance hard to get right. Novels are a big commitment, but you owe it to the writer you were when you started it to put your head down and plough on. Sometimes that 500 words you set yourself won’t come. I’ve learned not to sit there in despair, but go for a walk instead.

JH: What are you working on now, or is it a secret at this point?

BC: It’s not a secret–it’s a novel about the wife of a Scottish plant hunter in the early 20th century. I’m learning quite a lot about plants and botany, which is fun!

Visit the Beatrice Colin’s website here for more details about the author. You can buy a copy of To Capture What We Cannot Keep here, or on Amazon.

Lead photo credit : To Capture What We Cannot Keep