The Smart Side of Paris: The Corpses at Diderot’s House

Philosophy professor John Eigenauer shares fascinating and unknown histories of Paris in “The Smart Side of Paris” series

In 2005, Bodies: The Exhibition, opened in Tampa, Florida, eventually taking up permanent residence in Las Vegas. It was an imitation of the Body Worlds traveling exhibit of carefully preserved human and animal bodies, dissected to reveal their inner anatomy, which opened in Tokyo in 1995. At the Body Worlds exhibit, people could look inside a body and see muscles, tendons, and bones, organs and nerves, brain and eyes. The exhibit was a maddening success and has received more than 50 million visitors worldwide. It was billed as “the first of its kind.”

Except that it wasn’t.

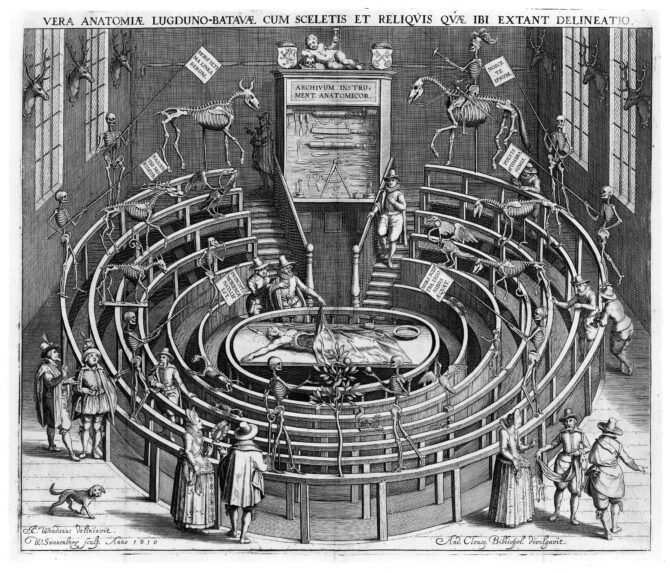

The first attempts to see inside real human bodies in 18th-century Paris took place in “anatomical amphitheaters,” where people could view actual dissections and learn about the mysterious human body. While the prospect of watching a dissection may sound revolting to those of us who didn’t attend medical school — Rousseau, for one, found the whole affair to be beyond disgusting — the Parisian public was fascinated. One wealthy young woman, the Comtesse de Coigny, even “traveled with a cadaver in the trunk of her carriage.”

Promotional poster for “Bodies: The Exhibition”

But dissections were more than morbid entertainment; they were science. The intellectual world of the age was exploding with the intrigue of new knowledge. The practical problem to expanding knowledge of the human body was: where to get fresh bodies? That was tricky. While technically acting legally in Paris, “resurrectionists,” i.e., grave robbers, caused public consternation as people fretted about their deceased relatives’ bodies being carved up post mortem. Overcoming their fears was a small problem, however, compared to digging up corpses in the freezing weather, when they could best be preserved, and working with them quickly, before decomposition rendered examination fruitless.

Now imagine for a moment what could make understanding the interior of the human body in 18th-century Paris even more difficult. Imagine that, in addition to having great difficulty simply finding corpses for dissection and study, and having to work quickly on them, you were barred from participating in anatomical theaters, barred from medical school, and poor. Such is the case with one of the most remarkable artists of the 18th century: Marie-Marguerite Biheron.

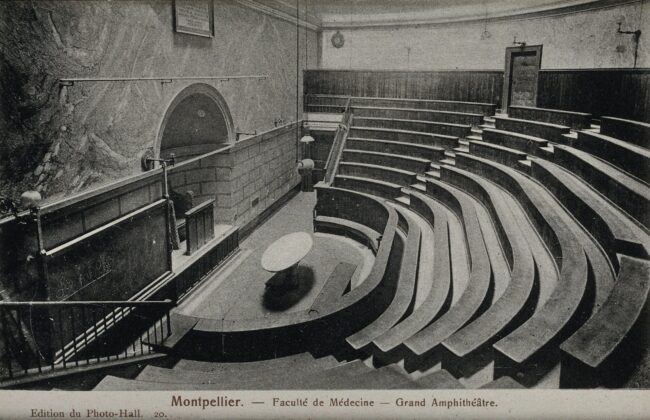

Theatrum anatomicum of the Faculté de Médecine de Montpellier. Wikimedia commons

Mademoiselle Biheron was trained as an artist, turned to sculpture, and eventually became obsessed with recreating “with incredible ardor… the most hidden secrets of the human structure” – to quote author Nina Rattner Gelbart. She snuck into anatomical theaters dressed as a man, found her way into hospitals after hours, and even built a dissecting arena in her garden to plunge her hands into the chests, entrails, and pelvic areas of the dead, obsessively peeling away protective layers to reach the precious organs behind the ribs, the diaphragm, and the urothelium. She spent countless thousands of hours learning the sizes and shapes of every organ, creating casts of each, hoping to bring them all to life in an anatomical venture the likes of which no one had ever attempted.

But once you have a kidney in your hands, there remains the onerous task of bringing it to life. Mademoiselle Biheron accomplished this by creating wax models of each organ from casts. But wax melts and is easily reshaped. To overcome this difficulty, Biheron created a proprietary formula that included “olive oil, turpentine, suet” and a series of “mystery ingredients” ranging from silk to feathers. Finally, she painted each organ accurately. Incredibly, her models never melted, bent, or broke, even when dropped.

Rue de l’Estrapade in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. Photo credit: LPLT / Wikimedia commons

Her models astonished even the most seasoned anatomists. The physician Charles-Augustin Vandermonde gushed that in Biheron’s creations, “There are countless beauties of detail that we cannot adequately describe… we must freely admit that there are parts that we have never seen as well in a cadaver.” The Gazette de France called her work “astonishing.” The Jesuit Journal de Trévoux, one of the premier intellectual journals of the day, called the models “anatomical marvels.” Sir John Pringle commented, “Mademoiselle, all that is missing is the stench.”

L’Institut de France, the headquarters for L’Académie française. Photo credit: Dennis G. Jarvis / Wikimedia commons

Her work was so unusual and so strikingly real that she soon became famous among the greatest thinkers of 18th-century France. Perhaps with help from luminaries such as Jean le Rond d’Alembert, Biheron was invited in 1759 to present her work to the Académie Française — the first woman to do so. In 1770 and 1771, she was invited back.

She became friends with Benjamin Franklin; Buffon used an illustration of her work in his monumental Histoire Naturelle; she impressed Lavoisier and Condorcet with her presentations at the Académie; Edme Mentelle commented that she “owned anatomy”; van Haller praised her work and used one of her models in the medical school he started in Germany; Grimm scolded the French government for failing to support her; d’Alembert claimed that “he learned more anatomy from her than from all the lessons at the Paris medical faculty”; one of her presentations at the Académie was offered specially for the king of Sweden, Gustav III.

Portrait of Denis Diderot, oil on canvas, signed: L. M. Van Loo / 1767. Louvre. Public domain

But perhaps her staunchest supporter was the great philosopher Denis Diderot, editor of L’Encyclopédie. Remarkably, Diderot and Biheron lived in the same building on rue de l’Estrapade. He admired her work so much that he recommended that Catherine of Russia use it in girls’ schools to teach them anatomy, and he entrusted his beloved daughter Angelique’s education about the human body to Biheron, as well as taking classes from her himself. He even worked the following into d’Alembert’s article in l’Encyclopédie on Cadavers: “there should be a law that forbids internment of a body before it is opened. What a wealth of knowledge we would gain in this way!”

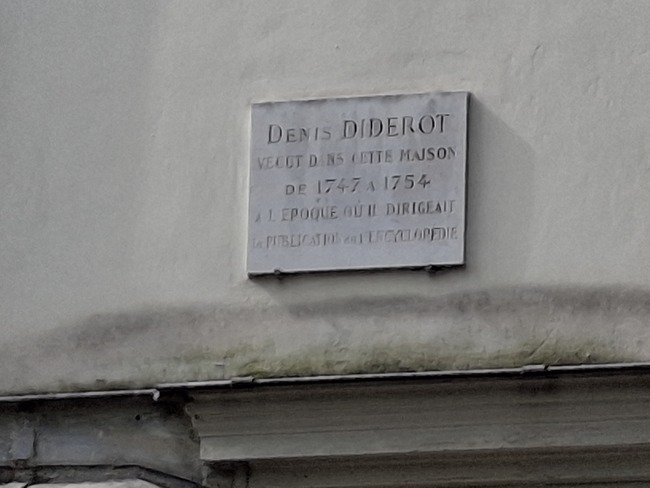

Diderot commemorative plaque at 3 rue de l’Estrapade. Photo: John Eigenauer

Perhaps Biheron’s greatest satisfaction, however, was using her intricate models to educate the public. In that same building where Diderot labored on l’Encyclopédie at 3 rue de l’Estrapade, she opened her own museum to display her lifelike creations: the Cabinet d’Anatomie artificielle. People came quite literally from all over Europe to see her perfectly formed anatomical creations. And when important visitors arrived who had not heard of the museum, Diderot dutifully escorted them to see it.

Today, there is a small plaque on the building at 3 rue d l’Estrapade, just above a Lebanese restaurant, commemorating Diderot’s residence. It reads, “Denis Diderot lived in this house from 1747 until 1754 at the time that he was directing the publication of L’Encyclopédie.” Sadly, there is no such plaque to recognize one of 18th-century France’s greatest artists: Marie-Marguerite Biheron. Á mon avis, the city of Paris would be remiss to fail to address this easily rectifiable omission.

Source: Quotes in this article come from Nina Rattner Gelbart’s Minerva’s French Sisters: Women of Science in Enlightenment France.

Author John Eigenauer outside the building at 3 rue de l’Estrapade

Lead photo credit : The anatomical theatre at Leiden University in the early 17th century. Public domain

More in 18th century, Denis Diderot, Marie-Marguerite Biheron, The smart side of Paris