The Smart Side of Paris: Smashing the Arc de Triomphe

On December 1, 2018, a group of protestors known as the “gilets jaunes” smashed a statue inside the Arc de Triomphe known as the Marseillaise. Newspapers worldwide featured the woman’s head with a gaping hole in the right side of her face. Macron visited the site; the Minister of Culture arrived to assess the damage. One reporter declared the statue “A symbol of France reborn.” The state vowed to punish the criminals. Ironically, the damage seemed to silence her scream for solidarity in pursuit of liberty. Today, the protests have abated, and moody youth have moved on to tagging juvenile slogans about the Israel-Palestine conflict on laundromat windows. The statue was dutifully repaired, and France’s dignity restored.

Statue on the Arc de Triomphe that was defaced. Photo via @CmdtDanielovic / Twitter

Six years later, the Marseillaise’s broken face once again adorned a sacred building: the National Archives of France. The occasion for her reappearance this summer (2024) was a brilliant exhibit titled “Sacrilège: the State, Religions, and the Sacred.” Loaded with wonderful images, the expo brought to life an intransigent theme in human history: the dividing line between the sacred and the profane. It asks us all to consider the meaning of sacrilege and the reason for its persistence.

Exhibit poster at the National Archives of France. Photo by John Eigenauer

Like so many things in the history of thought, it all begins with Socrates, who was “condemned to death for sacrilege, or more precisely for corrupting the youth in the ways of questioning the sacred.”

The Death of Socrates (1787). Jacques-Louis David. Oil on canvas.

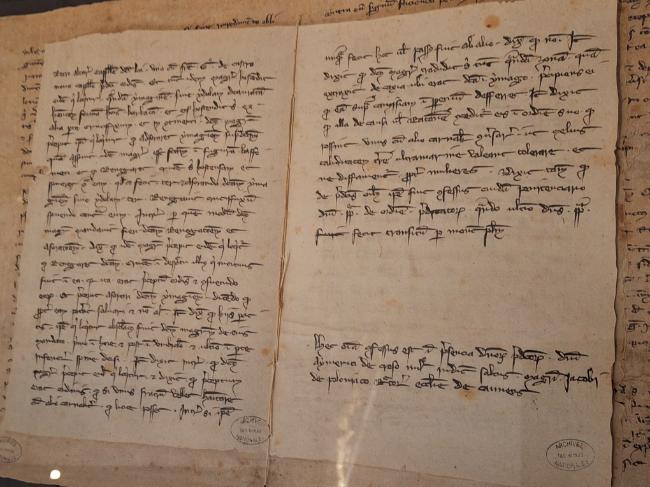

This type of condemnation was rare in antiquity; but the condemnation of sacrilege really took off in the Middle Ages because of the deeply held conviction that homogeneity of belief was the sine qua non of a kingdom’s social stability. And so, for example, even the Knights Templar, who tasked themselves with defending the sacred (specifically, Jerusalem and pilgrims on the road to Jerusalem) were accused of heresy. A good number of their order were burned alive. This 1307 document, on display in the Archives, is a record of the inquisition against the Knights Templar:

Exhibit document showing the Inquisition against the Knights Templar. Photo: John Eigenauer

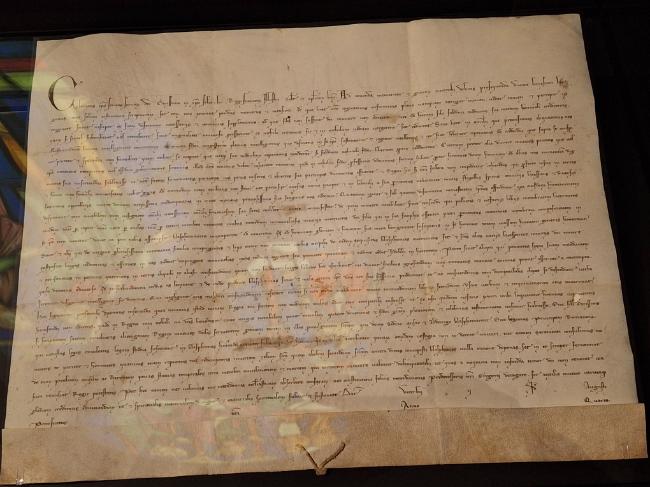

The medieval kings of France took the idea of unity of belief in their kingdom very seriously. Early on, Pope Innocent III initiated a crusade in Southern France to wipe out a splinter Catholic group called the Cathars (1209-1229) and thereby help the king obtain that utopian unity. Evidently, the idea got out of hand because in August of 1268, Pope Clement IV issued a religious mandate (called a “bull”) telling Louis IX to lighten up on the persecution thing. Here is the actual papal bull, on display in the National Archives:

Papal bull displayed at the National Archives. Photo: John Eigenauer

These early documents, according to the exhibit, demonstrate that the emergence of a centralized state reliant on royal power began almost immediately to build a wall around the “sacred” and prohibit any infraction against what the state considered to be sacred. This sacred terrain might be “royal power,” “the truth of the Catholic Church,” “the God-given order of society,” or anything that even smelled like critical thinking, questioning authority, or “sacrilege.” Under the newly emergent kingdoms, some things began to be defined as “sacred” and humans had no right to question anything sacred; moreover, royalty and ecclesiastical powers had the duty to quash any threat to sacrality.

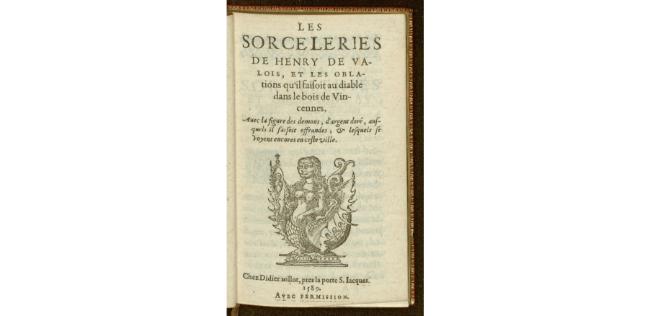

The exhibit pointed out that, as the Church and State began to operate essentially as one in much of Western Europe, the key term defining the separation between sacred and profane is “blasphemy.” In the age of the Reformation, blasphemy could be defined for Catholic powers as “all things Protestant,” and for Protestant powers as “all things Catholic” — propaganda worked wonders in facilitating hatred and justifying violence. A strong reminder of the lengths to which propaganda could leverage accusations of blasphemy, especially in this Catholic-Protestant divide, is a little book that was on display titled Les Sorceleries de Henri de Valois (The Sorceries of Henri of Valois, subtitled “and the oblations that he made to the Devil in the Bois de Vincennes”).

Les Sourceleries de Henri de Valois. Brigham Young Digital Collections.

This odd monster is intended to symbolize Henri III, who supposedly flirted with Protestantism and indulged in a degree of libertinism. In this frontispiece, he has the head of a lion “to show he combines luxury and self-concern with the audacity and arrogance of the lion.” He has “the breasts of a woman” to show that “this effeminate prince confused nature itself by being a hermaphrodite in his excesses.” He holds a portrait of Machiavelli in his right hand to show his crass manipulation of political power.

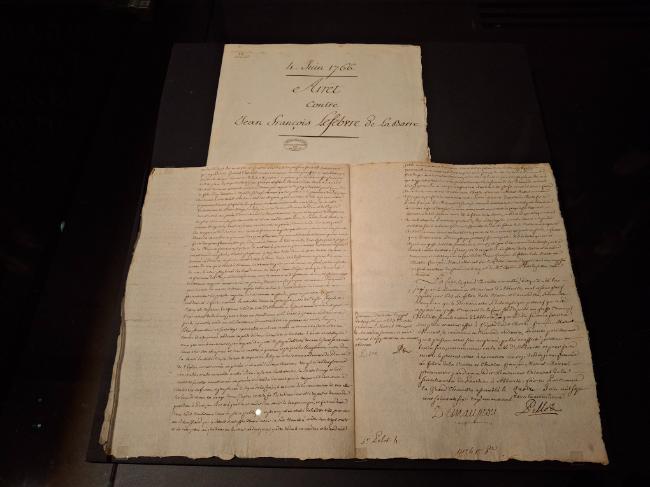

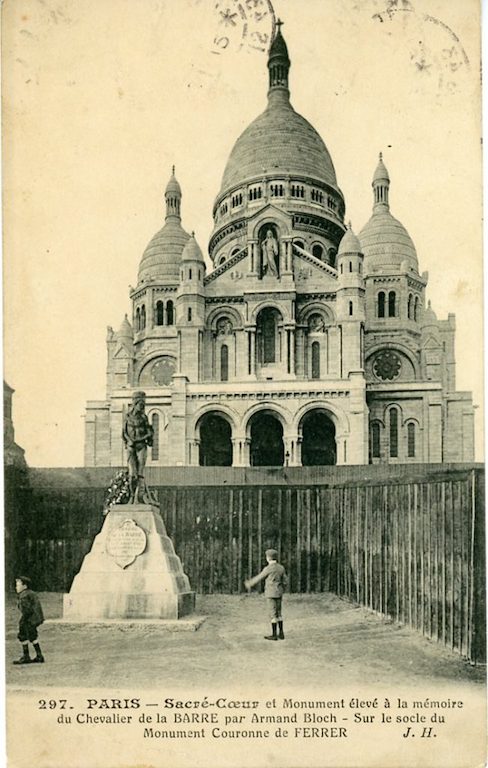

As the centuries march on, blasphemy is less frequently prosecuted. In fact, the last death sentence for blasphemy in France came in 1766 in the well-known case of the Chevalier de la Barre, whose statue, most unfortunately, stands inside a dog park in Montmartre. His full letter of condemnation is on display:

Judgment against Chevalier de la Barre. Photo: John Eigenauer

The case drew Voltaire’s ire and the indignation of many informed people, but too late to save de la Barre’s life. By 1766, the very idea of enforcing punishment against blasphemy in France had become laughably arcane. In fact, Melchior Grimm indignantly and sardonically reported to some of the most important people of Central and Eastern Europe:

“The decree [condemning the Chevalier de la Barre] declared him convicted of having passed twenty-five steps ahead of the procession of the Holy Sacrament without removing his hat or kneeling; of having uttered blasphemies against God, the Holy Eucharist, the Blessed Virgin, and the saints mentioned at the trial; of having sung two impious songs; of having showed respect and adoration for impure and infamous books; of having profaned the sign of the cross and the benedictions in use in the Church. This is what caused the cutting off of the head of an imprudent and poorly-raised child in the middle of France and the eighteenth century. In the countries of the Inquisition these crimes would have been punished with a month in prison followed by a reprimand.”

Monument to the Chevalier de la Barre – Paris, 18th arr. at Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre, circa 1906, vintage postcard. Public domain

The last volume of L’Encyclopédie was published the year before de la Barre’s conviction, the same year that Voltaire put an end to the Calas Affair. Blasphemy in France was supposedly dead. But so was the Chevalier de la Barre.

Despite the Enlightenment’s rejection of blasphemy, the expo’s organizers remind us, unfortunately, that blasphemy did not end when blasphemy ended; governments merely shifted their definition of the sacred. France ceased to prosecute crimes of religious concern and instead treated the state — and heads of state — as sacred. An 1814 declaration, for example, says that “the new king is inviolable and sacred.” In 1830, a cartoonist was sued multiple times for sketching King Louis-Philippe’s face to look like a pear.

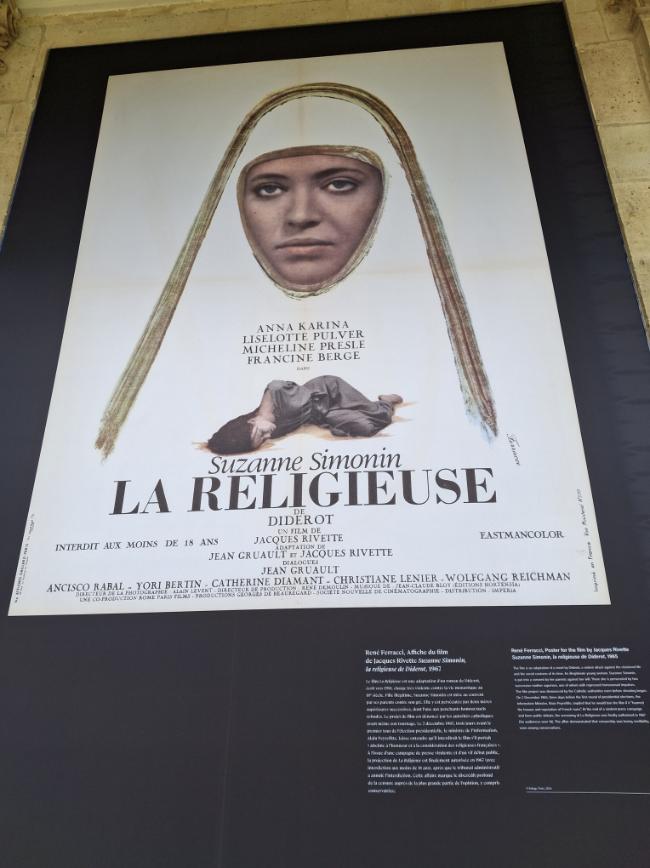

As the exhibit moves into the 20th century, it recognizes the continued problems that ensue from treating things as sacred. What are the tensions that arise from conflicts with free speech? What are the boundaries around personal offenses? Are creative projects free of condemnation for their satirical — or even overly truthful — portrayals of the “sacred”? When Jacques Rivette and Jean Gruault modernized (1965) Diderot’s scandalous 18th-century novel, La Religiuese (The Nun), the French public raised an outcry, and the minister of information banned the film. And, in fact, “mention of the ban was itself banned on French TV.” Diderot’s novel-turned-movie gets its props with a giant poster at the entry to the exhibit.

Photo: John Eigenauer

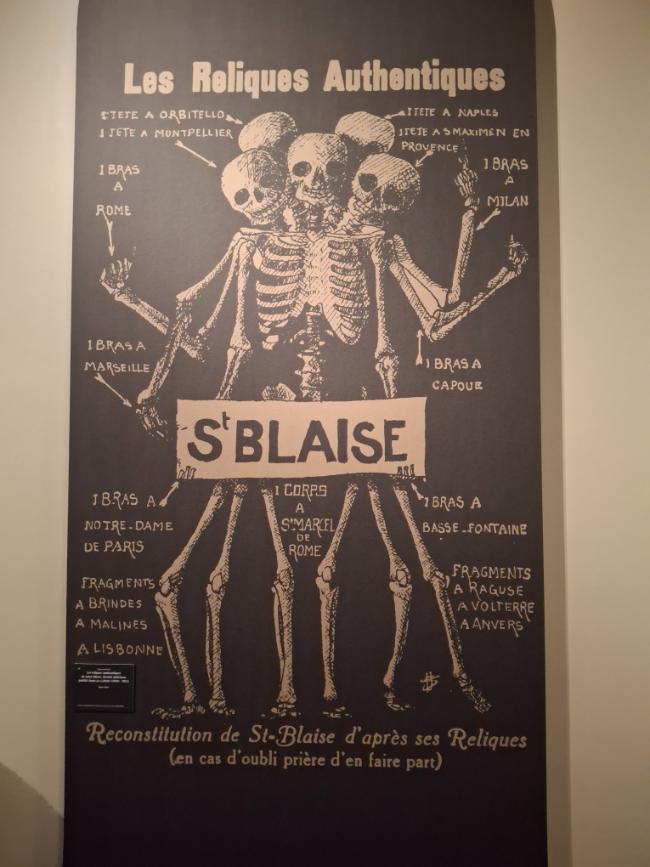

And what would an exhibit about sacrilege be without a little sacrilege of its own? The exhibit ends with the toothy smiles of Saint Blaise, delightfully labeled, “The Authentic Relics.” Mic drop.

Photo: John Eigenauer

Note: for those who speak French, a book documenting the entire exhibit is available on Amazon, at the National Archives, and at the bookstores inside the Bibliothèque Nationale (Mitterrand and Richelieu).

Lead photo credit : Arc de Triomphe. Photo: Jiuguang Wang /Wikimedia Commons

More in Arc de Triomphe, The smart side of Paris