The Four Generals who Saved Paris from the Nazis

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Which general liberated Paris in August 1944? It’s a question worth revisiting in this 80th anniversary year. One answer is certainly General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Western Europe. Another was given by nine-year-old Ginette Masson in an essay you can still see on display at the Musée de la Libération in Paris. She described watching Général Jacques-Philippe Leclerc leading his troops into southern Paris on the morning of August 25th that year. And what about General Dietrich von Choltitz, the German Commander in the city who ignored Hitler’s orders to ensure that Paris was left in ruins by the retreating German troops? They certainly all played decisive roles.

But the most determined force, the man who had refused to accept defeat and occupation, who fought tirelessly to win his country and his beloved Paris back, was Général Charles de Gaulle. Paris fell to Nazi Germany on June 14th, 1940. By the 18th, De Gaulle was in London, broadcasting a defiant speech on the BBC, calling on his countrymen to resist German occupation and fight back. “Has the last word been said? Must hope disappear? Is defeat final? No!” He spent the war supporting the Résistance and solidifying his position as the leader of “Free France.”

“Into the Jaws of Death,” an iconic image of the Normandy Landings. Robert F. Sargent. Public domain/ Wikimedia commons

After the D Day landings in June 1944, the march across northern France began and by August the liberating troops were approaching Paris. When de Gaulle was told by General Eisenhower that the plan was to bypass the city for now and push on to Alsace and the Rhine, he was unequivocal. Paris must be liberated immediately and for a number of reasons: its symbolic importance was huge, retaking it would boost morale, there was a risk that communist factions would take over the city, the Germans might destroy Paris rather than give her up. If Eisenhower didn’t send troops in immediately, he, de Gaulle, would do it himself. Eisenhower gave in. Within days the 2nd Armored Division and the 4th Infantry Division were sent to liberate Paris.

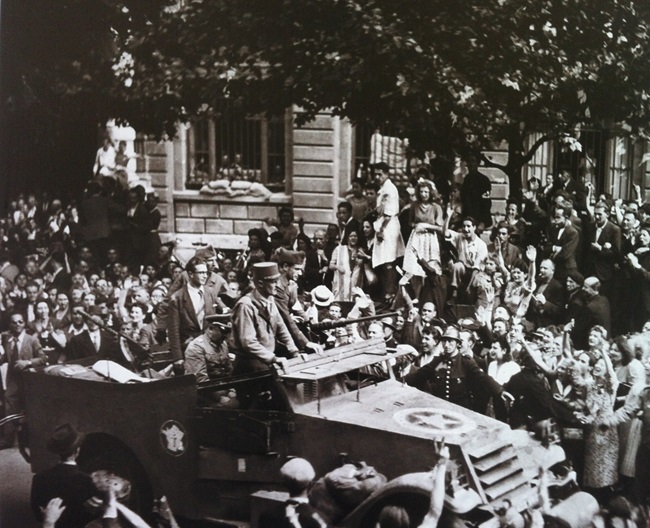

French crowds line the Champs-Élysées to view Free French tanks and half tracks of General Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division after Paris was liberated on August 26, 1944. Public domain. Wikimedia commons.

Dwight D Eisenhower had fought in France during World War I – and written a guide to its battlefields – and then had a distinguished army career which saw him appointed as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in December 1943. He spent time making preparations in London, then in June 1944 he gave the order to launch one of history’s most famous and successful military campaigns, the D Day landings in Normandy. From there the troops under his command fought their way across northern France, taking back towns and villages one by one. This was the basis on which the liberation of Paris became possible and Eisenhower’s planning and determination were key. Significantly, but perhaps less well remembered today, he then spent two years as President Truman’s Chief of Staff, directing the demobilization of the wartime army in Europe. Later, from 1953, he served as the 34th President of the United States. The naming of the 8th arrondissement’s Avenue du Général Eisenhower in his honor ensures that what he did for Paris will always be remembered.

Eisenhower (far right) with friends William Stuhler, Major Brett, and Paul V. Robinson in 1919, four years after graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point. Unknown photographer /Wikimedia Commons

Nine-year-old Ginette Masson wrote a school essay about what she saw happening near her home at the Porte d’Orléans in southern Paris on the morning of August 25th, 1944. “The Americans arrived,” she wrote excitedly, describing how she fist-bumped some of them and was given chocolate by others. “And I saw Général Leclerc go past.” Philippe de Hauteclocque had spent much of the war so far fighting for France in North Africa under the nom de guerre of Philippe Leclerc. It was as the general commanding the 2nd Armored Division that he landed back on French soil at the beginning of August 1944.

The march to Paris took several weeks and Leclerc’s troops liberated other places en route, including Alençon, still remembered today as the first French city liberated by a unit under French command. A statue of his tall, lanky figure leaning on his trademark cane was installed there in 1970. As he approached Paris on August 24th, aware of the valiant efforts of the Résistants and others in the city, Leclerc sent a plane to fly over the city and drop the encouraging message: Tenez bon, nous arrivons – Hold on, we’re coming. On the afternoon of the next day, Leclerc accepted the surrender of the German Commander, Dietrich von Choltitz. After his death in a plane crash in Algeria in 1947, Général Leclerc was interred in the Invalides after the state funeral befitting his heroic status.

Général Leclerc in Normandy with men of the 501st tank regiment. Public domain/ Wikimedia Commons

General von Choltitz had been commanding the German troops in Paris for only a few weeks, but it fell to him to deal with the increasing disorder. The Résistants were in action all over the city and a general strike began just days before the liberation. At his headquarters at the Hôtel Meurice on the Rue de Rivoli, Choltitz received personal orders from Hitler that “Paris must not pass into the enemy’s hands, except as a field of ruins. ” His motivation for disobeying the order was probably a mix of admiration for the city, of resignation that defeat was inevitable, and of his knowledge that Hitler, whom he had seen personally just a few weeks earlier, was a madman whom he could no longer support.

Dietrich von Choltitz with Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque and Jacques Soustelle in the M3 Scout Car. Unknown photographer /Wikimedia Commons

At 3:30 pm on August 25th, Choltitz surrendered, signing a document presented to him by Général Leclerc at the nearby Préfecture de Police. He spent the rest of the war being held at Trent Park, a country house outside London which had been requisitioned by the British government. No charges were brought against him and he was released in 1947. In his memoirs, published in 1951, he referred to himself as “the savior of Paris.” He was, of course, an occupying Nazi officer with a war record including many allegations of cruelty. But it is also true that if he had made different decisions in the last days of August 1944, much of Paris could have been destroyed.

There’s no doubt that the glorious 25th August belonged, above all, to Général de Gaulle. His triumphant speech, given on that afternoon outside the Hôtel de Ville, made a proud reference to “Paris liberé !” The British historian Cecil Jenkins has written of this occasion that de Gaulle “announced grandly at the Hôtel de Ville that the liberation of the capital had been carried out by the French, by the French alone and should there be any misunderstanding, by nobody but the French.” The Président-to-be should, he felt, have acknowledged more fully all the help from his allies which had made the triumph possible. But really, who can underestimate the pride de Gaulle felt as his four-year defiant struggle against his country’s oppressors was brought to an end?

Statue of De Gaulle on the Champs Élysées. Photo credit: Marian Jones

Plaque on the statue of De Gaulle. Photo credit: Marian Jones

The 26th August was set aside for celebration. Général de Gaulle led a victory parade down the Champs Élysées, starting by relighting the Eternal Flame at the tomb of the unknown soldier under the Arc de Triomphe. He was accompanied by General Leclerc and by leading members of the Paris Resistance and greeted by throngs of excited, grateful, relieved Parisians. Some of de Gaulle’s most distinguished allies had found him very difficult to deal with – President Roosevelt expressly ordered that he be kept away from the D Day landings and Winston Churchill had referred to him as “the heaviest cross I have to bear” – but no one disputed the major role he had played in this victory.

The statue of Général de Gaulle which stands just off the Champs Élysées shows him striding down the most iconic avenue in the city, just as he did in August 1944. Those who witnessed it bore testament to his bravery, for he walked single-mindedly, ignoring the shooting which broke out several times. He was going to Notre Dame where a Te Deum was to be held in thanksgiving for the liberation. Even when he arrived, the gunshots continued, but he took no notice. A BBC journalist described the scene thus: “The General walked straight into what appeared to me to be a hail of fire … he went straight ahead, without hesitation, his shoulders flung back, and walked right down the centre aisle, even while the bullets were pouring about him. It was the most extraordinary example of courage I had ever seen.”

Lead photo credit : De Gaulle Statue

More in D-Day, French history, General De Gaulle, Generals, Normandy landing, Paris, WWII

REPLY