Siege of Paris Part Two

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It was Plato who suggested that ‘necessity is the mother of invention.’ Parisians trapped by the Siege of 1870 certainly took this epithet to their hearts. As we discussed in the first article on the Siege, several schemes were implemented to smuggle messages and military despatches out of the city. Messages literally sailed over the heads of the encircling Prussians, in balloons and by homing pigeons. But both methods were fraught with danger and some messages never arrived. Inventors were constantly thinking of clever new solutions to get the messages through, since besieged Paris depended on despatches for military intelligence and for morale. Pigeons and balloons were clearly not enough.

Boules de Moulins

Not all of the inventions that came out of the siege were successful. One that failed completely was actually not so bad in principle. In the town of Moulins, a cunning plan was hatched to float hollow zinc balls, containing hidden messages, down the Seine and into Paris. The devices, some of which survive, were known as Boules de Moulins. The plan was straightforward – the boules would float down the Seine and be caught in huge nets slung between the banks of the river when they reached Paris. For some reason, which hasn’t been fathomed to this day, not a single one of the Boules de Moulins were snagged by the nets during the Siege, and the plan was eventually abandoned. Ironically a few boules were retrieved years later – as late as the 1980’s in fact – with their messages still intact. They can be viewed at the Postal Museum. (Musée de La Poste, 34, boulevard de Vaugirard, 15e)

Not all of the inventions that came out of the siege were successful. One that failed completely was actually not so bad in principle. In the town of Moulins, a cunning plan was hatched to float hollow zinc balls, containing hidden messages, down the Seine and into Paris. The devices, some of which survive, were known as Boules de Moulins. The plan was straightforward – the boules would float down the Seine and be caught in huge nets slung between the banks of the river when they reached Paris. For some reason, which hasn’t been fathomed to this day, not a single one of the Boules de Moulins were snagged by the nets during the Siege, and the plan was eventually abandoned. Ironically a few boules were retrieved years later – as late as the 1980’s in fact – with their messages still intact. They can be viewed at the Postal Museum. (Musée de La Poste, 34, boulevard de Vaugirard, 15e)

The Advent of Microphotography

A much more successful endeavour was the application of early microphotography techniques to the problem of moving messages in volume. Charles Bareswil, a modest chemist from Tours, suggested to the Post Master General, Germaine Rampont-Lechin, that it might be useful to employ the newfound technique of photographing documents and reducing their size. Upon receipt, the microfilm messages could be scaled up and read with ease by means of a magic lantern. The plan was seized upon by the postal department. They asked the help of the photographer René Dagron, who had demonstrated microphotography techniques at the Exposition Universelle in 1867. The Minister of Finance, Ernest Picard, gave him permission to proceed, dubbing him “chef de service des correspondences postales photomicroscopiques“. Dagron was assigned two balloons, the Niepce and Daguerre, to enable him and his colleagues to fly out of Paris to work in Tours. Amongst the team were Dagron’s son-in-law, Jean Poisot, Gnocchi, his assistant, Pagano the pilot and Albert Fernique, a distinguished engineer and expert in microfilm technology. They set off for Tours on November 12th, 1870.

A much more successful endeavour was the application of early microphotography techniques to the problem of moving messages in volume. Charles Bareswil, a modest chemist from Tours, suggested to the Post Master General, Germaine Rampont-Lechin, that it might be useful to employ the newfound technique of photographing documents and reducing their size. Upon receipt, the microfilm messages could be scaled up and read with ease by means of a magic lantern. The plan was seized upon by the postal department. They asked the help of the photographer René Dagron, who had demonstrated microphotography techniques at the Exposition Universelle in 1867. The Minister of Finance, Ernest Picard, gave him permission to proceed, dubbing him “chef de service des correspondences postales photomicroscopiques“. Dagron was assigned two balloons, the Niepce and Daguerre, to enable him and his colleagues to fly out of Paris to work in Tours. Amongst the team were Dagron’s son-in-law, Jean Poisot, Gnocchi, his assistant, Pagano the pilot and Albert Fernique, a distinguished engineer and expert in microfilm technology. They set off for Tours on November 12th, 1870.

Disaster

The trip was doomed. The Prussians shot down the Daguerre, carrying the pigeons and the scientific equipment needed for the experiments. In the Niepce, Dagron and his team started desperately to throw sandbags out of the balloon to gain height and avoid the Prussian guns. The bags split however, and they were forced to scoop sand out of the basket as best they could. Eventually, thinking they were beyond Prussian territory, they began their descent. But strong wind took control and they landed firmly back in Prussian-held land, upside down in a tree. A passing farm worker spotted their difficulties and offered them the use if his horse and cart, and by this means some of the group continued their journey towards French-held territory. One might have thought their troubles were then over, but the waiting French troops didn’t believe the wild tale about microfilm and sandbags and balloons and promptly charged them with spying. After further adventures and quite a lot of hiding, the scientists arrived in Tours. Fernique arrived on the 18th and Dagron on the 21st November, nine days after setting off.

The Work Continues

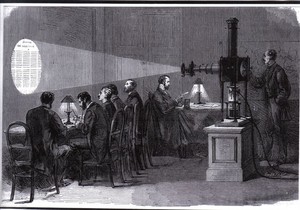

By December 15th the team recommenced their work. The microfilms they produced weighed just 0.05gm, and a pigeon could carry twenty at a time. Each one contained dozens of messages. Upon receipt, the films were carefully removed from the pigeon, placed between two sheets of glass and projected onto a screen. Teams of clerks would then transcribe the contents and pass the messages on to the addressees. It was a triumph of invention and ingenuity. The total number of microfilms passed on in this way is estimated to be in excess of 150,000 – containing as many as a million personal letters. The Times reported on the Prussian response:

By December 15th the team recommenced their work. The microfilms they produced weighed just 0.05gm, and a pigeon could carry twenty at a time. Each one contained dozens of messages. Upon receipt, the films were carefully removed from the pigeon, placed between two sheets of glass and projected onto a screen. Teams of clerks would then transcribe the contents and pass the messages on to the addressees. It was a triumph of invention and ingenuity. The total number of microfilms passed on in this way is estimated to be in excess of 150,000 – containing as many as a million personal letters. The Times reported on the Prussian response:

“…the Prussians, it is said, with their usual diabolical cunning and ingenuity,

have set hawks and falcons flying round Paris to strike down the feathered

messengers that bear under their wings healing for anxious souls.”

Parisian homing pigeons were made of stern stuff, and the Prussian tactic was largely unsuccessful.

Anna Meakin is the author of Paris by Plaque – Montmartre, which explores the city’s history through the historical plaques of Paris. She’s now writing the next book in the series, about the Left Bank. Paris by Plaque is available from Amazon UK & US and the Museum of Montmartre. Please click on her name to read more about Anna and her other stories about historic Paris published by BonjourParis.

Lead photo credit : Boule de Moulins Stamp

More in Boules de Moulins, French history, history, René Dagron