The Painter of Modern Life: Renoir and the Spirit of Baudelaire

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

During the last third of the 19th century, Baron Haussmann’s modernization of Paris was well underway. The subjects of modernity and progress consumed the minds of avant-garde writers and painters. Poet and essayist Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) used modernity as his creed. His rallying cry for artists to “be of their time” would greatly affect the Impressionist painters. Modernity would soon be represented on the canvases of Impressionists who embraced the theme of la vie moderne. Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) shared Baudelaire’s philosophy of capturing the fleeting moment. His masterpiece, The Luncheon of the Boating Party, reveals that Renoir shared Baudelaire’s values of modernity, leisure, fashion and the acceptance of all classes.

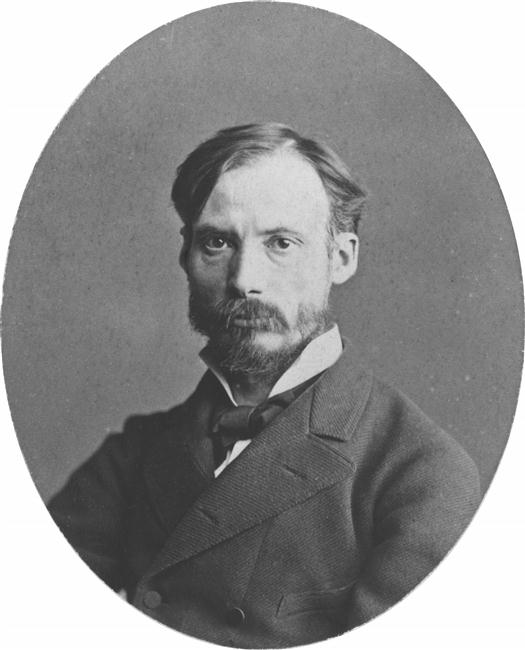

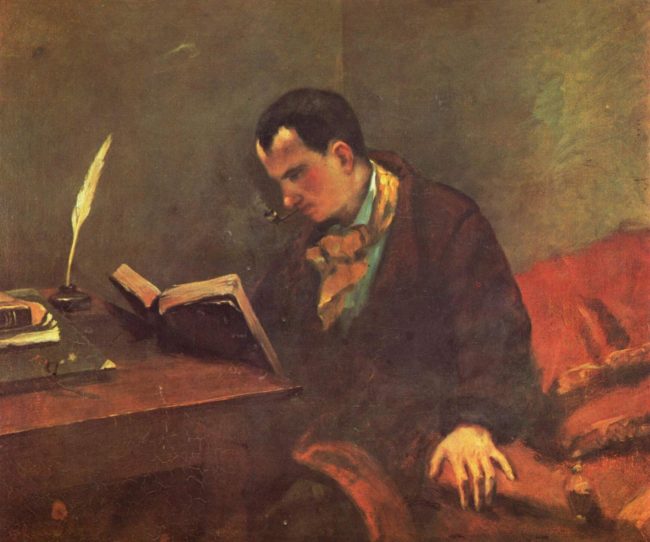

Auguste Renoir. Image credit: Public domain. Unknown Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

The industrialization of Paris inspired Baudelaire. Before 1848, impeded streets and narrow bridges characterized the city. Under the auspices of Emperor Napoleon III, Baron Haussmann made plans for grand boulevards to strike through the core of Paris. By the 1870s, hundreds of kilometers of old streets had been altered and widened. Baudelaire’s writings reveal his excitement of the Paris crowds and his ability to move anonymously among them as a flâneur. He was a dedicated observer of the new Parisian streets.

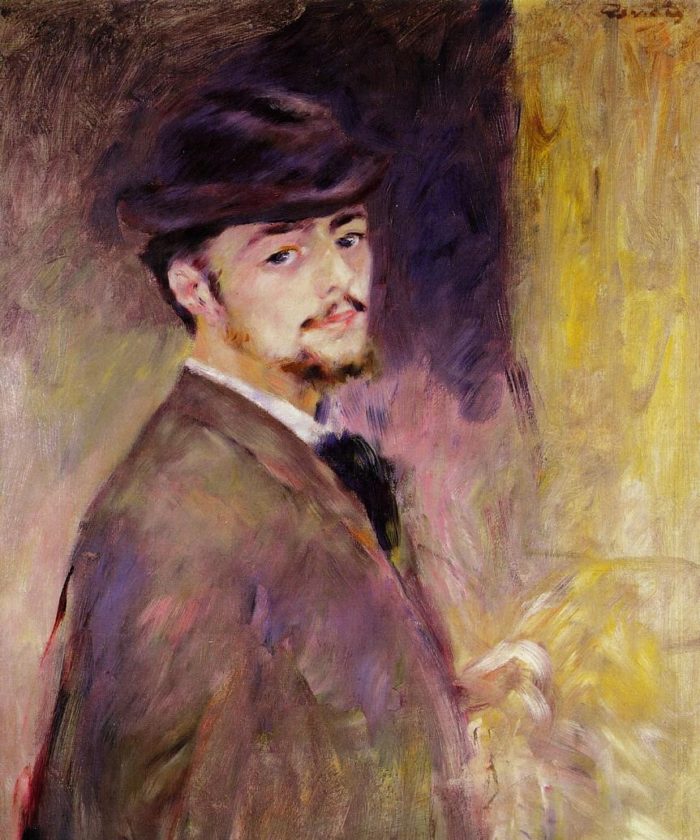

Self-Portrait at the Age of Thirty Five. Oil on canvas. Image credit: Public domain. WikiArt, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1876

Baudelaire’s writings were the catalyst that launched the movement toward modern art. In 1846, Baudelaire published his landmark review of the Paris Salon with his call to artists to “be of their time,” and to create art that interacted with the present world, rather than that which emulated the past. Baudelaire’s rhetoric was largely ignored; it was his later 1863 essay, The Painter of Modern Life that had a tangible impact on the Parisian art world.

The Painter of Modern Life was an essay published in Le Figaro. Baudelaire urged artists to cast aside historical subjects and plunge into the present day, to embrace the new modernity. Overall, he believed that an artist should represent their time, and be able to create an enduring work of art from a fleeting look at modern life. To capture that passing moment, a painter with the characteristics of a flâneur was needed. Baudelaire’s ideal flâneur was a passionate observer of life, but also a man of leisure, enjoying himself, but missing nothing.

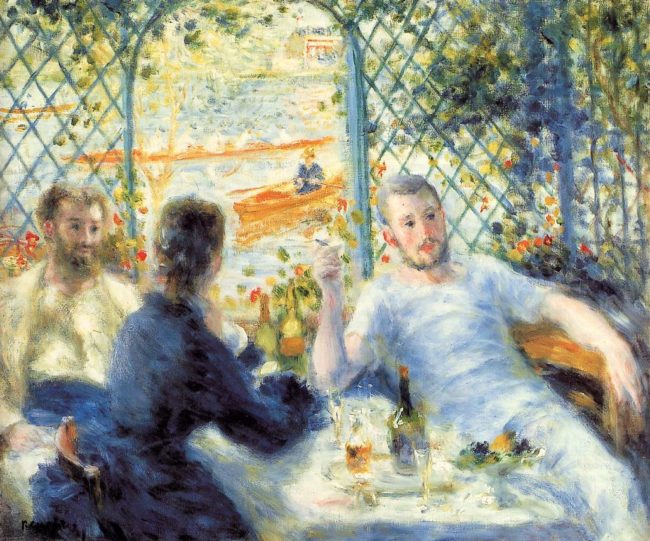

By the 1880s, Impressionist artists had answered Baudelaire’s plea for modernity and were devoted to portraying contemporary life. However, by this time, Baudelaire was long dead and the social realism found in Paris had shifted to the suburbs. Parisians thirsted for leisure. Impressionism had, up until now, aligned itself with the modern urban culture of café concerts, cabarets, and vaudeville. However, with the development of railways, the focus fell on the leisure activities in the banlieue – swimming and boating. Baudelaire likely would have appreciated the transient moment represented in Auguste Renoir’s 1880-81 exploration of leisure in suburban Paris. The Luncheon of the Boating Party depicted a popular weekend destination for leisure-seeking Parisians – the riverside suburb of Chatou. Parisians would take a train to suburban Île Saint Martin to take advantage of the swimming and boating the Seine offered alongside the Restaurant Fournaise.

Restaurant de la Maison Fournaise. Photo: Comite regional du Tourisme Paris

Renoir wanted to paint aspects of la vie moderne but he shunned the ugliness of industrial progress. He wanted to portray the beauty of a location while capturing the essence of leisure and relaxation. The working class artist sought to create the warm, social harmonies that he feared were disappearing amid the cold decadence of urban Paris. He succeeded in this with his Luncheon of the Boating Party. Renoir depicted a group of holidaymakers at the restaurant and boating establishment of the Fournaise family. Renoir envisaged boating as the perfect expression of leisure in the modern life of the middle class. Boating, swimming, and picnicking, allowed for the inhibition, freedom, and self-indulgence necessary for an escape from the grind of the city. Sailboats and canots in the Seine are seen in the far left of the painting.

The strong colors and textures and the liberated pleasure-seeking that Renoir painted were adamantly modern. Renoir’s luncheon at the guinguette of the Fournaise family shaped an Eden of social harmony. It was on the terrace of the Restaurant Fournaise where Renoir arranged 14 friends, models, and colleagues from a wide range of classes and occupations to pose for his painting. Renoir’s models included artist and patron Gustave Caillebotte, the son and daughter of the owner of the establishment, an editor, a seamstress, a journalist, an actress and a model who was one step away from prostitution. Baudelaire would have appreciated the variety of models Renoir included and the fact that he painted celebrities and working women equally.

In this setting, we see the detritus of a convivial meal: beer glasses, wine glasses, grapes from a fruit bowl, swizzle sticks, discarded lemon slices, used napkins, a keg of brandy, and wine bottles at various levels of consumption. A wide range of male and female clothing and accessories are worn. The model who would one day be Madame Renoir brought her lap dog. In this regard, Renoir is the silent flâneur observing every detail. Although this painting was posed over several weeks, the impression that it is but a fleeting moment is very successful.

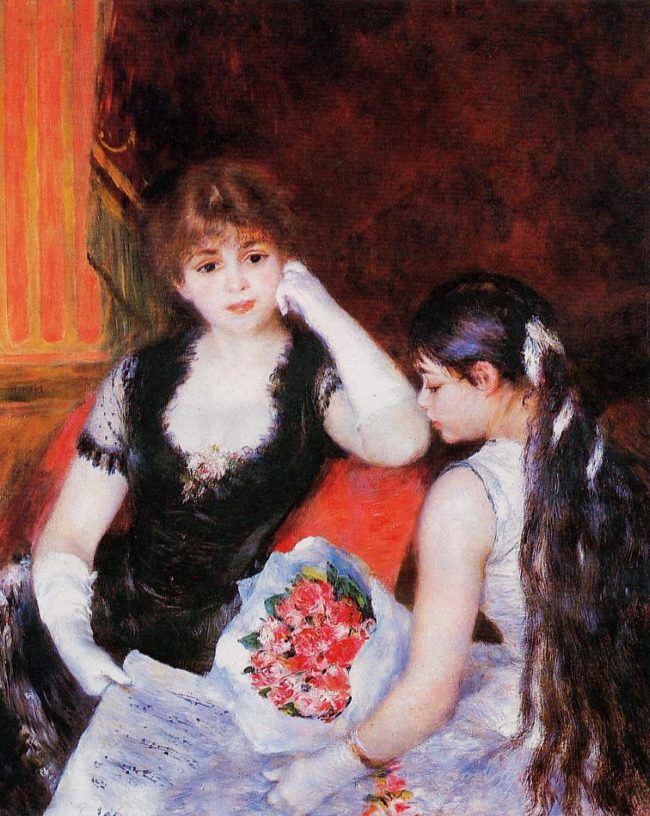

At the Concert (Box at the Opera), Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1880. Oil, canvas. Image credit: WikiArt, public domain.

The women depicted in Renoir’s painting wear the latest fashions whether they are society girls, actresses, or simply owner’s daughter clothed in a boating costume. The spirit of Baudelaire would have praised Renoir for not being “too lazy to distill whatever beauty modern clothing could contain.” Baudelaire wanted artists to paint women “not only in her bearings and the way she moves and walks, but also in the muslins, the gauzes, the vast iridescent clouds of stuff in which she envelops her self.” We can enjoy the history lesson in costume that Renoir is delivering to 21st century viewers. Baudelaire would have delighted in the difference in costume between the sportsmen and the top-hatted editor because they represented class opposites.

Although Renoir disliked the chic hardness of modern life, industrial reality did reveal itself in Renoir’s art. In The Luncheon of the Boating Party, practically hidden under the top left awning, is the train bridge leading back to Baudelaire’s industrial Paris.

Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise (1879), Pierre-Auguste Renoir – art book. Image credit: Public domain.

In a work of art like The Luncheon of the Boating Party, we can capture some of the excitement Renoir felt from observing contemporary life. The painting embodies the quote from Baudelaire, “To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home.” The poetry and art of Baudelaire and Renoir employed the modern concepts of capturing the fleeting moment, the idea of leisure and observation, and the importance of fashion and inclusivity. They embodied the principle that artists and poets should represent the time they lived in. In doing so, they provided the world with a valuable insight of their era.

Visitors can follow in Renoir’s footsteps visiting the Maison Fournaise on what is now called the Île des Impressionnistes. This restaurant is open seven days a week and you can sit on the same balcony as Renoir and his friends. Take a selfie – I’m sure Baudelaire would approve!

Le restaurant de la Maison Fournaise

Ile des Impressionnistes

3, rue du Bac – 78400 Chatou. Tél: +33 (0)1 30 71 41 91

email: [email protected]

Lead photo credit : The Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880 - 1881. Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Image credit: Public domain. WikiArt

REPLY