Maxime Du Camp: The First French Travel Photographer

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the latest in a series of photo essays on early French photographers

Maxime Du Camp (1821-1894) was the first French travel photographer. In 1849, Du Camp and his friend, Gustave Flaubert, both 27-year-old college dropouts, sailed to Egypt to explore ancient sites. While there, Flaubert kept a journal of the trip and Du Camp took photographs of the pyramids, the Sphinx, the temples of Luxor and more.

The trip was truly adventurous. They fought off bandits, were briefly arrested as spies, had liaisons with belly dancers and prostitutes, both male and female, drank until drunk and took all sorts of drugs.

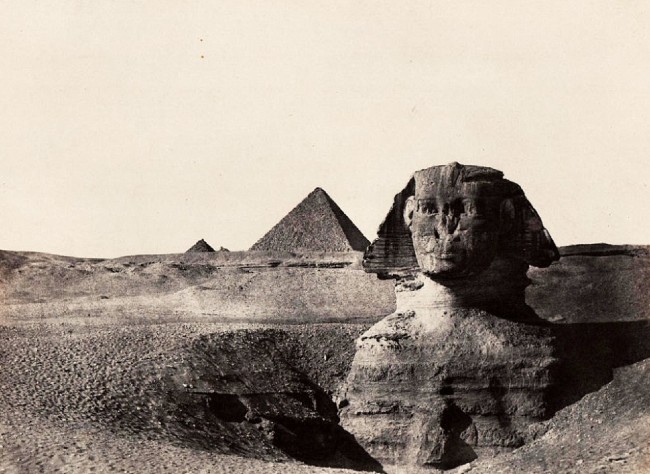

Apparently none of these experiences interfered with their productivity. Flaubert wrote prodigiously and well. Du Camp took hundreds of photographs, developing them on the spot in a tent set up in the desert. In his journal, Flaubert wrote of the Sphinx, “No drawings that I have seen convey a proper idea of it — best is an excellent photograph that Max has taken.” Du Camp wrote, “I am pale, my legs trembling. I cannot remember ever being moved so deeply.”

Maxime Du Camp, public domain

Returning to France in 1850, Flaubert began to write in earnest, finishing Madame Bovary just two years later. His journals were published in 1972 under the title, Flaubert in Egypt.)

Du Camp made prints from his negatives and sold them an album entitled Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, Syrie. The album, the world’s first travel photography book, created a sensation and its influence in initiating travel photography as a genre cannot be overstated. From that time on, thousands of photographers, both professional and amateur, have followed Du Camp’s lead.

Nor was photography the only beneficiary of Du Camp’s adventures. Trends in fashion, design, architecture, art, archaeology — all of our fascination with the ancient civilizations of the Near East — are in large part due to his captivating images.

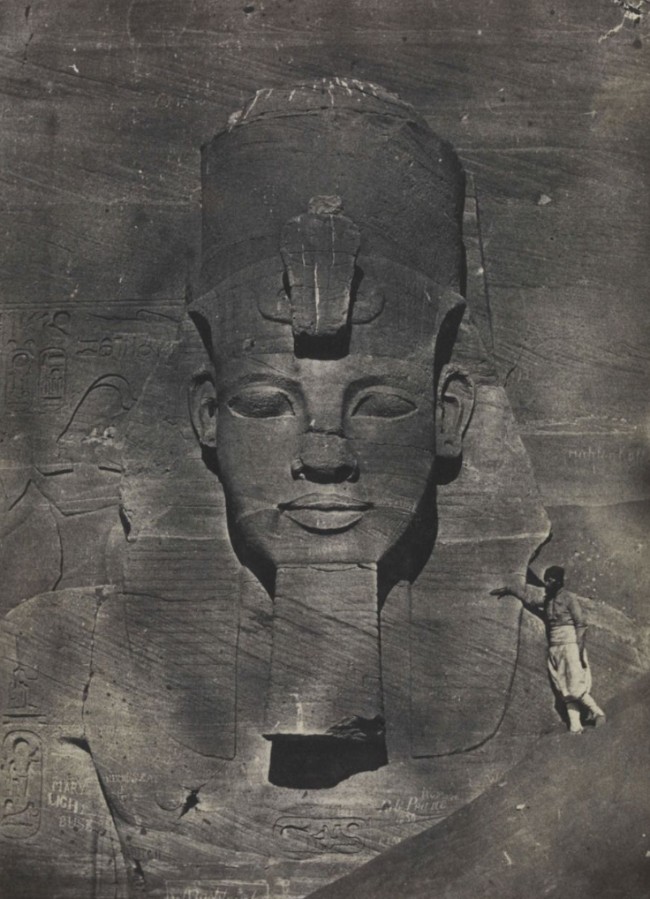

Looking at Du Camp’s work should convince us that we are in the hands of a master artist. Du Camp’s photographs of ancient Egyptian monuments do justice to their monumentality. No long-distance views. We are right up close to them. They fill the frame.

Maxime Du Camp, public domain

This choice to fill the frame may seem obvious but it is not. How often to do we see tourist photos in which the main subject is relegated to long-distance miniaturization? DuCamp made no such rooky mistakes.

Compare, for example, these photographs of Stonehenge, the famous prehistoric site in England. Here the image is not monumental:

Stonehenge by Fern Nesson

Here Stonehenge appears slightly more monumental.

Stonehenge by Fern Nesson

And finally here is Stonehenge in all its monumental glory:

Stonehenge by Fern Nesson

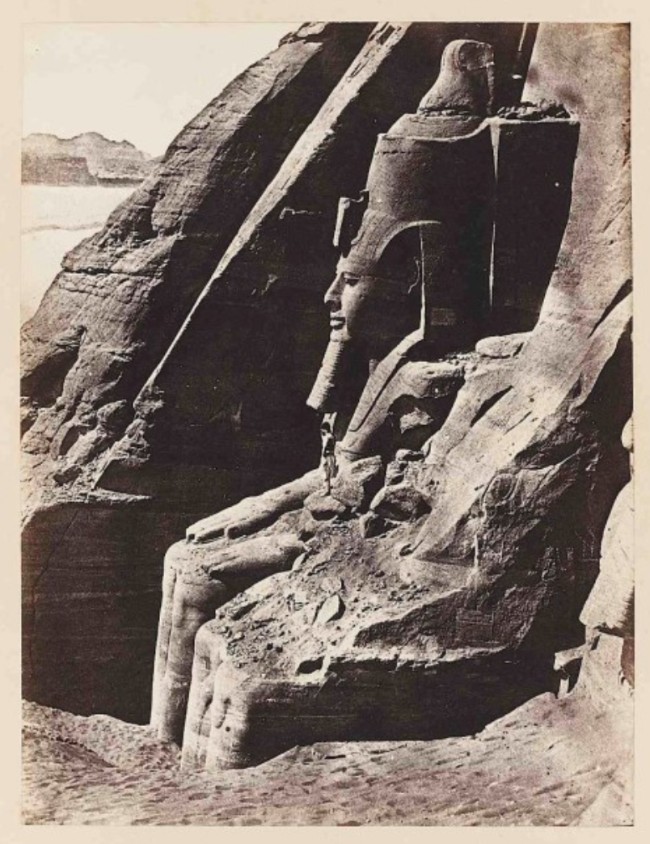

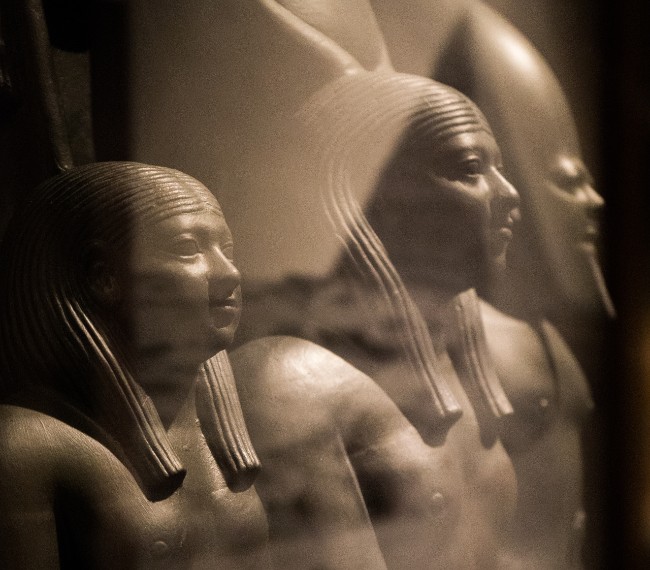

Further evidence of Du Camp’s sophisticated artistry is his choice to photograph from interesting angles and with an excellent eye toward lighting. He shot architectural monuments to highlight their immensity. But for Rameses II, he shot also to capture personality. Taken in profile, Rameses comes to life. He seems almost to be smiling.

Shooting from the side also creates a contrast of shadow and light on Ramses’ face. The light outlines his features, making them more contoured so that his face reads more as human than as stone. In Du Camp’s image, a monument becomes a portrait as well.

Maxime Du Camp, public domain

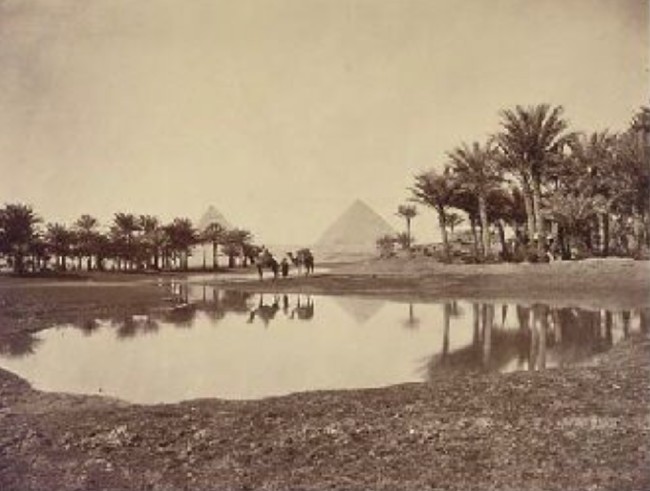

Du Camp also knew how to use context. His Sphinx (above) is set beautifully in relation to the pyramids behind. She guards the tombs of the pharoahs, just as she should. So, too, Du Camp photographs the two pyramids below in their desert oasis. On their own, they would be striking monuments; in their setting, they become a heavenly resting place fit for two kings.

Maxime Du Camp, public domain

Good photography is more than camera, focus and technique. It imparts meaning and message visually through angles, setting, distance, framing. Du Camp was a master of all.

Homage à Maxime Du Camp. Photo by Fern Nesson

Lead photo credit : Maxime Du Camp, public domain

More in 19th century, French photographers, French photography

REPLY