Don’t Miss: Henri Rousseau and Paula Modersohn-Becker Exhibits in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

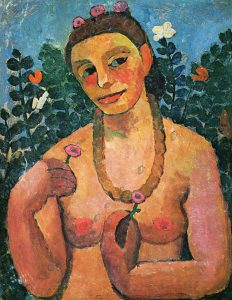

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait With Blue Irises, c. 1905, distress on canvas, 40.7 x 34.5 cm, Kunsthalle Bremen-Der Kunstverein in Bremen

Two excellent retrospectives this summer – Henri Rousseau at the Musée d’Orsay and Paula Modersohn-Becker at the Musée de l’art moderne de la ville de Paris — offer the opportunity to study two artists whose brief careers overlapped and converged in Paris. In 1906 Modersohn-Becker met Rousseau through the German sculptor Bernard Hoetger.

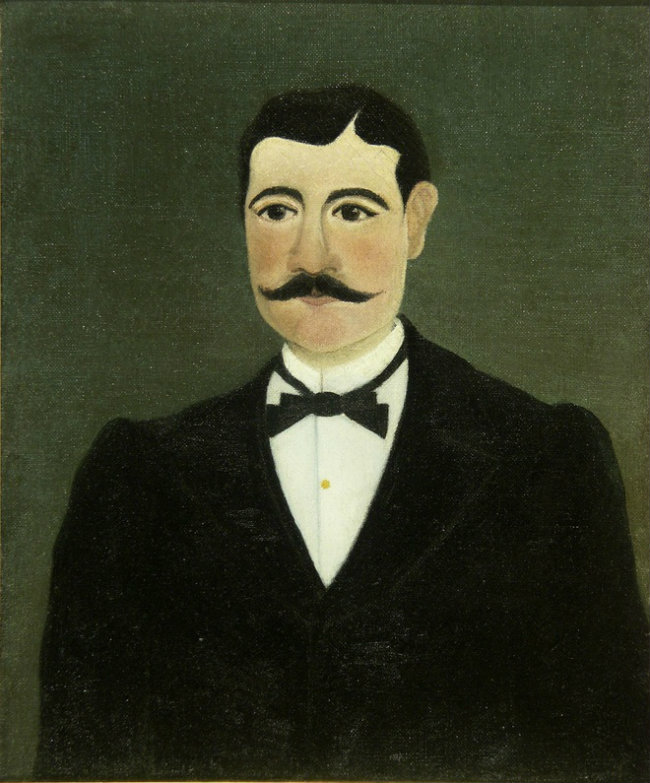

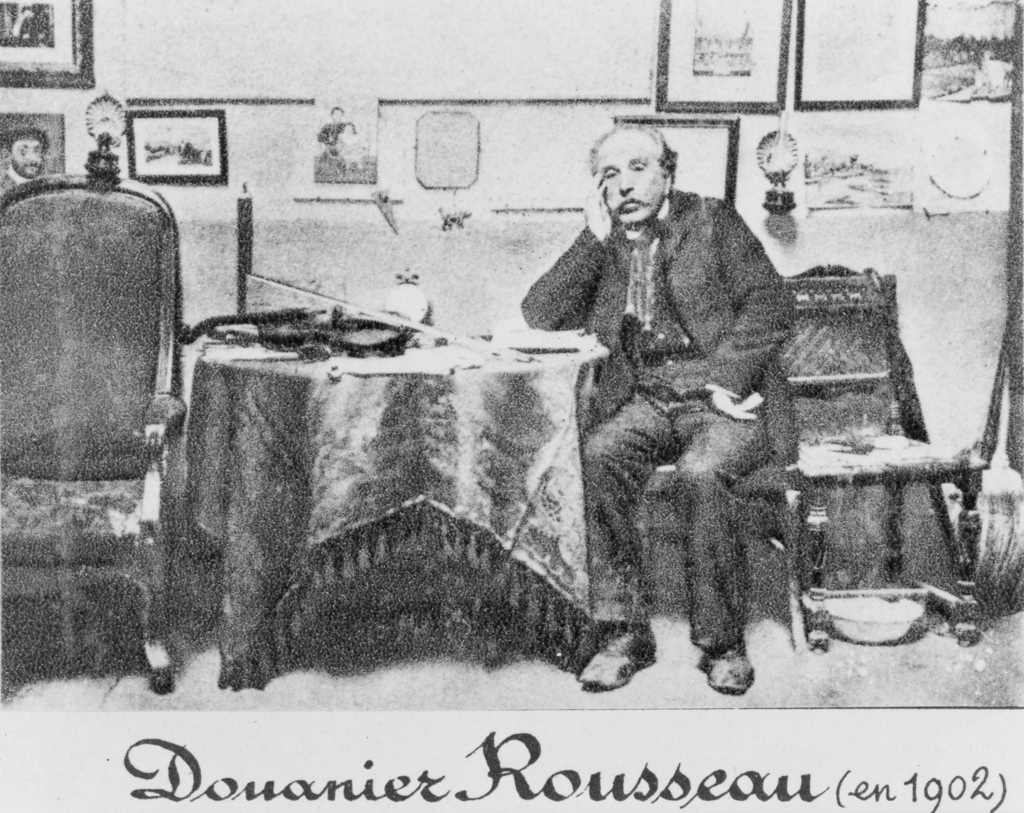

Henri Rousseau, called le Douanier, Self-Portrait (“Moi-Même”), 1890, oil on canvas, 136 x 113 cm, National Gallery in Prague.

At the time, Rousseau had only painted seriously for the last twenty years, as he started his career after age 40; Modersohn-Becker, thirty-two years his junior, had devoted herself to art for the last ten. Sadly, her life ended the next year, on November 20, 1907. Rousseau lived until September 2, 1910.

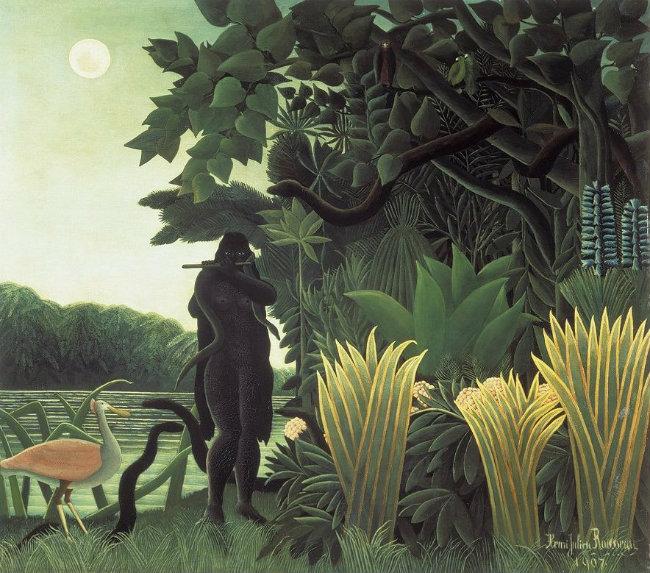

In the exhibition Henri Rousseau: Archaic Candour, we see their paintings hanging side by side, like kindred spirits. They both simplified forms, flattened figures and firmly delineated contours in a deliberately anti-classical fashion. The Rousseau curators Beatrice Avanzi and Claire Bernardi call this tendency “archaic,” because it seems to hark back to pre-classical antiquity and late medieval “primitifs” which the both artists studied in their temple of art, the Louvre.

Henri Rousseau, called le Douanier, Portrait of Madame M., c. 1890, oil on canvas, 198 x 114.5 cm

Paris, musée d’Orsay, © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Portrait of Lee Hoetger, 1906, oil on canvas, 92.4 x 73.5 cm, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen © Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

(Exhibited side by side in Henri Rousseau: Archaic Candour, Musée d’Orsay.)

Henri Julien Félix Rousseau was born in Laval on May 21, 1844 to a family of modest means. His father dealt in metals and hardware until he suffered reverses which resulted in selling the family’s comfortable home. Henri became a boarding student at his high school when the family moved to another town (which may account for his individualism and resourcefulness).

After high school, Rousseau briefly worked for a lawyer and studied law. Losing interest, he joined the army in 1863, served for four years, and then, after his father died in 1868, settled in Paris with his mother and entered civil service. In 1871, he was promoted to tax collector of goods entering Paris (hence the nickname “le Douanier,” customs officer). By then he had been married to Clémence Boitard, the landlord’s 15 year old daughter, for three years. The couple had six children, but only two survived to adolescence and only one, Julie, to adulthood. In 1888, Clémence died at age 35. Ten years later he married Josephine Noury.

Henri Rousseau, The Wedding Party, 1905, oil on canvas, 163 x 114 cm, Paris, Musée de l’Orangerie © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) / Hervé Lewandowski.

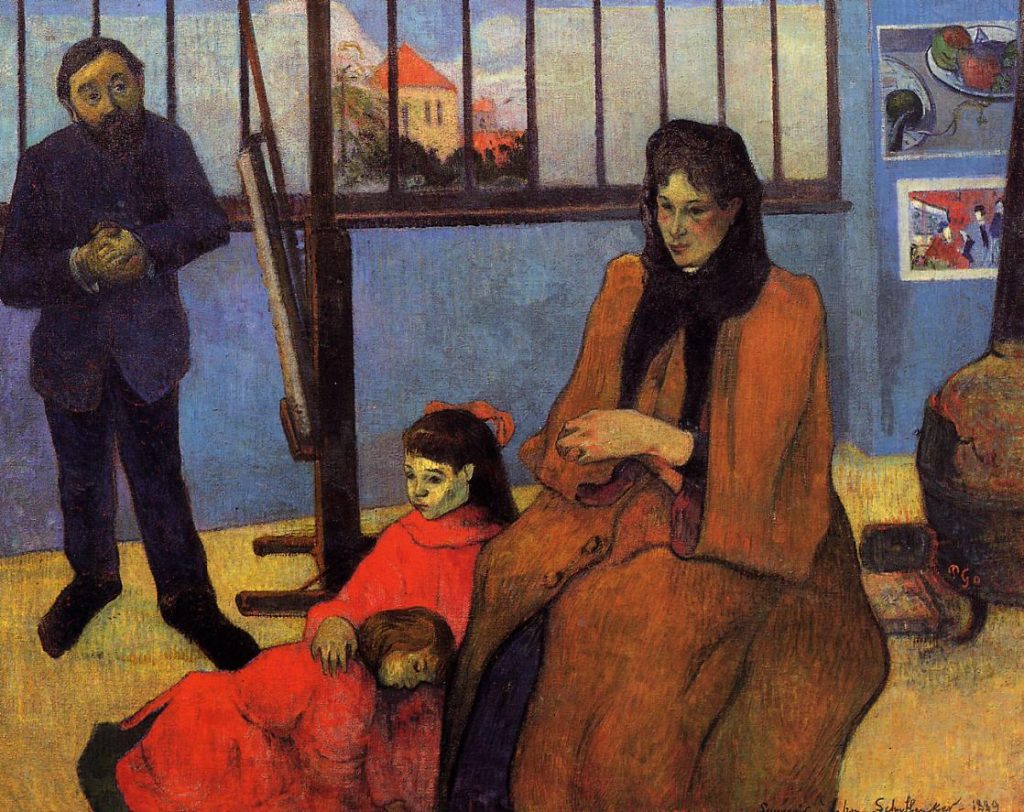

Paul Gauguin, The Schuffenecker Family in the Studio, 1889, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 110 cm, Paris, Musée d’Orsay © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt.

Rousseau started to paint on Sundays in his early 40s and retired at 49 in order to paint full-time. He was able to submit his work to the unjuried Salon des Indépendants in 1886 (two years after this salon made its debut). The cost for exhibiting was only 25 francs. Post-Impressionists Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Odilon Redon also exhibited in this newly-established unrestricted Salon, wherein Rousseau’s bold naïve style attracted attention. According to the poet/art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, Gauguin loved the Douanier’s use of black, which (the art critic claimed) came from Rousseau’s close examination of Paolo Uccello.

Apollinaire’s friend and fellow poet/critic André Salmon wrote in his book Henri Rousseau (1961) that he introduced the Dounaier to the Louvre and would often meet him by chance as he wandered through the galleries. “What interests you today?” Salmon would ask. Rousseau would reply: “One can’t remember all their names, Albert. There are so many.” (Salmon duly noted that the artist failed to remember his friend’s name as well.) At the Louvre, Rousseau studied the smooth blended surfaces achieved by the great academic masters. He admired their precision and clarity. He once said to Picasso: “You and I are the most important artists of our time: you in the Egyptian style and I in the modern.” And yet, the older man preferred traditional painters, like late-nineteenth century artists Jean-Léon Gérome and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, to the true “moderns,” like Picasso, Matisse and André Derain – who sincerely adored Rousseau’s ability to “really paint” (the artist-writer Michel Georges Michel recollected in his book From Renoir to Picasso, 1954).

Henri Rousseau, dit le Douanier, Portrait of Frumence Biche, 1892, oil on canvas, 46 x 36 cm, Nice, Musée International d’Art Naïf Anatole Jakovsky, N.Man.002.P0720 © Musée International d’Art Naïf Anatole Jakovsky, Nice.

But what does this anti-classical “archaic candour” really mean? Essentially, the words indicate simplicity and authenticity. For the young moderns, Rousseau seemed to purify art, rescuing it from Art Nouveau’s ostentation and ornate pretention. The word “archaic” suggests a return to a less complicated era, before urban industrialization and materialistic bourgeois values took over social norms. Pared down to its clear, readable forms (as opposed to fugitive effects in Impressionism), Rousseau’s paintings affirm stability and easy access to familiar subject matter. Moreover, they are refreshingly unself-conscious. Women do not conform to classical idealized beauty and scenes of city life do not prettify the facades or inhabitants. Sometimes the scenes record contemporary life in an eerie fashion; sometimes the scenes describe a dream. One can say that his work anticipated Surrealism in its unfiltered stream-of-conscious. This unfettered imagination may account for its “candour.”

Henri Rousseau, Child with Doll, 1904-5, oil on canvas, 67 x 52 cm, Paris, Musée de l’Orangerie © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) / Franck Raux.

Picasso claimed that he found a Rousseau portrait cheap enough to paint over. However, the image intrigued him and he decided to seek out the painter. The Spaniard and his “gang” (Apollinaire, Salmon, Max Jacob and others) championed Rousseau’s work right away. However, few critics sympathized and decided instead that the Douanier was a mere simpleton or charlatan, tricking these tricksters (Picasso’s Gang) who only amused themselves by pretending to take him seriously.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Portrait of a Girl with Fingers Spread Against Her Chest, c. 1905, distemper on canvas, 41 x 33 cm. Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal

© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In 1908, Picasso’s Gang hosted the famous “Rousseau Banquet” in Picasso’s studio at the Bateau Lavoir, all the way up on the hills of Montmartre. It may have been their way of reciprocating in kind the many soirées they attended in Rousseau’s studio in Montparnasse since 1907. Rousseau’s festive occasions included poetry readings, concerts of songs and instrumentals, oration, and listening to Rousseau’s famous fiddling, all the while accompanied by donations of food and drink from neighbors, collectors and dealers who dropped in as the evening wore on. (Rousseau survived on a paltry retirement income supplemented by lessons in diction, painting and music.)

Did Paula Modersohn-Becker attend the Rousseau’s numerous soirées on the rue de Plaisance? Alas, we do not know. She left Paris with Otto at the end of March 1907, the year Rousseau began these little evening gatherings, and then she died of an embolism nearly eight months later on November 20, 1907 at her home in Worperweder, just three weeks after giving birth to her daughter Mathilde.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl Holding a Glass with Yellow Flowers, 1902, distemper on cardboard, 52 x 53 cm, Bremen, Kunsthalle Bremen-Der Kunstverein in Bremen, © Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

Modersohn-Becker, unlike the autodidact Rousseau, studied art in various schools in her native Germany and in Paris. She was born on February 8, 1876 in Dresden to the son of a university professor and daughter of a minor aristocrat. The family moved to Bremen in 1888 for her father’s job with the railroad. Her father’s half-sister in London introduced her to art and arranged for lessons there. Upon Paula’s return to Bremen she enrolled in a teacher training program to satisfy her parents’ pragmatism. She also arranged for private art lessons on the side. This lasted from 1893 to 1895. In 1896, she moved to Berlin to study at the Association of Women Artists and in 1897, she moved into an artists’ colony in Worpswede, northeast of Bremen, where she met her future husband, the painter Otto Modersohn.

Photo of Paula Modersohn-Becker, 1904.

On New Year’s Day 1900, Paula and her closest friend in Worpsweder the sculptor Clara Westhoff set out for Paris to study art. Paula attended the Académie Colarossi, which accepted women, and anatomy lessons at the École des Beaux-Arts. She returned to Worpsweder in June. The following September, German-Czech poet Maria-Reiner Rilke joined the artists’ colony group. On April 28, 1901 he married Clara Westhoff and on May 25th, Paula married Otto. She also became a stepmother to Elsbeth, Otto’s daughter by his first wife, who died in 1900. The Rilkes had a daughter Ruth on December 12th and moved to Paris without Ruth in 1902. Paula would visit them and study art in 1903 and 1905, but eventually these short sojourns were not enough. On February 23, 1906, Paula left Otto to live permanently in Paris.

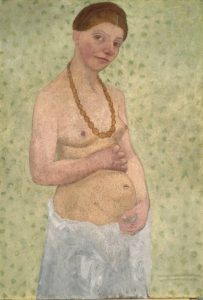

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait with Amber Necklace, 1906, distemper on paper, 62.2 x 48.2 cm, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Ludwig Roselius Museum, Bremen.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait on Sixth Anniversary of her Wedding Day, 25 May 1906, distemper, 101.8 x 70.2 cm, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen.

Her goal was to become “something” in the art world, to find her own authenticity that might gain recognition among her peers. She often socialized with Clara and Rainer Maria Rilke in Paris and through them gained access to an exploding experimental art world. Another German couple, Lee and Bernard Hoetger, introduced her to various artists including Henri Rousseau in 1906 (according to Bernard’s recollections). Enchanted by Gauguin’s exotic primitivism, van Gogh’s colorful expressionism, and the Louvre’s masterpieces (from Egyptian Fayum funerary portraits c. 100 BC-300 AD to J.A.D. Ingres’ somewhat mannered Mademoiselle Rivière of 1806), she discovered ample resources to guide her anti-classical approach to contemporary subjects. Therefore, to responsibly analyze Modersohn-Becker’s paintings, one has to investigate all the art she mentioned in her diaries and letters, besides Rousseau and his modernist followers.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Still Life with Gold Fish Bowl, May-June 1906, distemper on cardboard, 50.5 x 74 cm, Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal, © Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Nude Mother and Child in Her Arms, Autumn 1906, distemper on canvas, 80 x 59 cm, Museum Ostwall im Dortmunder U, Dortmund, © Museum Ostwall im Dortmunder U, Dortmund .

In her compelling book Paula Modersohn-Becker: The First Modern Woman Artist (Yale, 2013), art historian Diane Radycki points out the unprecedented modernism of Modersohn-Becker’s women, especially nude mothers who exude an authentic naturalness that male artists had not achieved heretofore. Modersohn-Becker’s retrospective in Paris gives us an opportunity to examine her uniquely modernist approach to the maternal nude and her modernist preference for a medium that contributed further to an unidealized female figure. Her choice of distemper paint, a water-based recipe that mixes chalk and pigment with an animal glue or milk-based casein, produces a rough, pasty texture, as if a liquid base were thickened with fine sand. The effect in Modersohn-Becker’s work adds a rustic quality to the image, contrasting quite starkly with the polished refined surface of an academic painting—the surface Rousseau strove to achieve with his oils. Modersohn-Becker, on the other hand, chose oil far less often and that choice seems quite deliberate.

Henri Rousseau, Snake Charmer, 1907, oil on canvas, 167 x 189.5 cm Paris, Musée d’Orsay © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Right: Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl Playing a Flute in the Forest of Birch Trees, 1905, distress on canvas on wood, 110.4 x 90.2 cm, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Brême © Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

Modersohn-Becker’s accelerated development as a modernist in Paris may well be the reason the retrospective of this German came to the Musée de l’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. For the time she spent in Paris transformed her native talent into an original approach to modernism. Radycki claims this made her the “first modern woman artist” in art history. One wonders whether her work might have gained greater notoriety had she stayed in Paris or if she might have attended the Rousseau Banquet in 1908, where she would have met Picasso and his friends. Unfortunately, fate had other plans and only now, one hundred years later, do we have the privilege to view Modersohn-Becker’s work in one venue in the city that gave her so much to live for.

I cannot emphasize strongly enough how fortunate we are to have these particular Rousseau and Modersohn-Becker exhibitions on view at the same time in Paris. Those lucky enough to have already visited these shows know that reproductions cannot do the work justice. If you are fortunate enough to live in Paris or visit Paris this summer, please put these two important exhibitions high on your list of top priorities. This chance may not occur again within our lifetimes.

For more information about the exhibitions and catalogues, please visit the museums’ websites: Henry Rousseau: Archaic Candour at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, March 22 – July 17.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: An Intensely Artistic Eye at the Musée de l’art moderne de la ville de Paris, April 8 – August 21.

More in French Art, Paris art, Paris art exhibitions, Parisian Artists