Héloïse and Abélard: A Story of Passion and Sorrow

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“To one flowing with milk and honey… I send the flood of delight and the increase of joy…. I give you the most precious thing I have, myself, firm in faith and love, steady in desire.” These words were written in 12th-century Paris by the young Héloïse to her tutor Abélard, with whom she’d fallen truly, madly, deeply in love. Their story is recalled especially around Valentine’s Day, but in fact there is much more to it than a simple tale of passion and romance.

Peter Abélard was in his early 30s when he arrived in Paris and began to make his mark as a popular teacher with brand new ideas. In the early 12th century, his habit of encouraging students to debate, rather than just accept ideas from on high, was radical, but students loved it and flocked to be taught by him. Before long, he had set up his own school at the Abbey of Mont-Sainte-Geneviève on the Left Bank and was attracting attention all over the city.

Héloise was the orphaned niece of Canon Fulbert at Notre Dame. She’d been well educated at a convent in Argenteuil, just outside Paris, and in 1115, when she was about 15, her uncle brought her to Paris to live with him and continue her studies. She was formidably well-read, understanding both Latin and Greek and interested in ideas, philosophy and debate. She was also very beautiful. Abélard recalled many years later, when writing about first meeting her, that she was “of no mean beauty, and she stood out by reason of her abundant knowledge of letters.”

19th-century representation of Héloïse, chosen to appear in a list of noted women writers. Public domain

So besotted was he that, as he put, he “sought to discover means whereby I might have daily and familiar speech with her.” Claiming that his lodgings were expensive and noisy, Abélard persuaded Héloïse’s uncle to let him live with them. Abélard later remembered the uncle begging him to give his niece instruction “whensoever I might be free from the duties of my school” and expressed his surprise at this in very frank terms: “the man’s simplicity was nothing short of astounding to me; I should not have been more smitten with wonder if he had entrusted a tender lamb to the care of a ravenous wolf.”

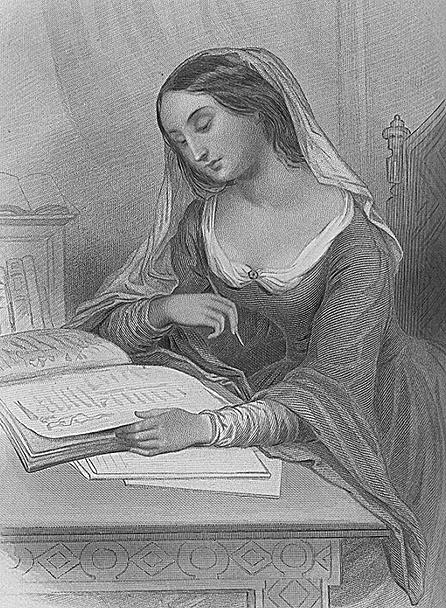

And so it all began. The fullest description of the love which grew between the two comes from a long letter, Historia Calamitatum Mearum (A History of my Misfortunes) written by Abélard long after their separation. “Under the pretext of study,” he wrote, “we spent our hours in the happiness of love.” They talked more of love, he explained, than of “the books which lay open before us,” and he wrote candidly about the pleasure they took in each other. “No degree in love’s progress was left untried by our passion, and if love itself could imagine any wonder as yet unknown, we discovered it. And our inexperience of such delights made us all the more ardent in our pursuit of them, so that our thirst for one another was still unquenched.”

“Abélard and his pupil Héloïse”, painted by E. B. Leighton in 1882. Public domain

Their bliss was not to last. So many centuries later, it’s hard to be sure of the exact facts and the order in which they happened, but historians generally agree that Canon Fulbert found out what was happening and immediately insisted that they separate. As Abélard had noted, there was a naivety about the elderly churchman and it seems that the couple continued to meet until, perhaps inevitably, they discovered that Héloïse was pregnant. Disguised as a nun, she ran away with Abélard to his native Brittany, where she gave birth to their son Astrolabe in 1118.

Exactly what happened next is a little confused. We know that a secret marriage was arranged, after which Héloïse returned to the convent at Argenteuil and that shortly after that Canon Fulbert sent a gang of men to break into Abélard’s room where they attacked and castrated him. Abélard then retired to the Abbey at St Denis, where he taught and wrote for the rest of his life and Hélöise, perhaps after hearing of his decision, took her vows to become a nun and, eventually, an abbess.

Current facade at 24 rue Chanoinesse closing the courtyard of the old Saint-Aignan chapel, likely site of the secret marriage of Héloïse and Abélard. Photo credit: Mbzt / Wikimedia commons

Most of what we know of their story comes from eight letters, discovered at least a century after their deaths. The first is the aforementioned Historia Calamitatum Mearum, written not to Héloïse, but to a fellow monk, but which she discovered a decade or so after their separation. She immediately wrote to Abélard and a correspondence developed. They exchanged a further six letters, written in Latin, during the 1130s, and it is on these that most of what we know about their relationship is based.

Héloïse’s first letter to Abélard’s is heart-rending. Nothing, she said, had changed. She still thought longingly of him and of their love. In fact, it consumed her, despite her vows and the life she now led as a nun. “Even at Mass,” she wrote, “lewd visions of the pleasures we shared take such a hold upon my unhappy soul that my thoughts are on their wantonness instead of on my prayers. Everything we did, and also the times and places, are stamped upon my heart along with your image… I live through it all again with you.”

She reproached him too, accusing him of neglecting her after they had both withdrawn to religious orders, which, she says, was “your decision alone.” Why had he not written to her? She recalled that he’d written her many letters during their romance and also songs about her, which he’d sung in public. Could it be, she asked, that “it was desire, not affection which bound you to me, the flame of lust rather than love?” Abélard replied that his lack of correspondence “must not be attributed to indifference,” then continued his letter by lecturing her on the power of prayer. It really does read as if he was more resigned to their separation than she could ever be.

In her next letter, Héloïse admitted that this response had made her cry, writing “You made the tears to flow which you should have dried.” She tried again to explain her feelings, telling Abélard she could not repent because repentance is not real “if the mind still retains the will to sin and is on fire with its old desires.” Abélard replied, advising her to think now only of Christ and to trust that he and she would be “reunited in heaven.” After that, Héloïse seems to have given up hope. She no longer mentioned her feelings, but focused on seeking Abélard’s advice on the affairs of the convent and he answered her questions, addressing her as “Héloïse, my sister whom I love and revere in Christ.”

Shakespeare wrote that “Love is of man’s life a thing apart, ‘Tis woman’s whole existence.” Is that the explanation here? Or is that perhaps a little unfair to Abélard? It remains uncertain whether he sent Héloïse definitively to the convent, or whether he’d intended this as a temporary solution and changed his mind only after the cruel violence he suffered at the hands of his attackers. Had Canon Fulbert always planned this cruel punishment? Or was it a terrible misunderstanding, carried out because he believed that Abélard had abandoned his niece? Was it only when Héloise heard that Abélard had retreated to a monastery that she gave up all hope of a life with him and took her vows instead?

Perhaps Abélard’s motives are not completely clear, but Héloïse’s unequivocal voice rings out across the centuries. She loved Abélard completely and unselfishly, as revealed in her doubts about marrying him. She feared marriage would mar his reputation in the church and was reluctant, as she put it, to “rob the world of so shining a light.” Also, for her it was their love which mattered and marriage would add nothing to that. She preferred, she wrote, “love to wedlock and freedom to chains.” She believed passionately that women should choose a man for love alone and that any woman who sought wealth, possessions or status through marriage was “offering herself for sale.” That, from a 12th-century woman, was nothing short of radical.

The tomb of Héloïse and Aberlard in Pere-Lachaise Cemetery. Photo: Marian Jones

Abélard expressed the joy of their love very eloquently. Héloise did that too, but she was also able to describe its terrible cost. Queen Elizabeth II, addressing the families bereaved by the 9/11 attacks, used – perhaps unwittingly – Héloise’s argument when she said “Grief is the price we pay for love.” Nine centuries earlier, Héloïse put it like this: “My sorrow for what was taken from me is the greater for the fuller joy of possession which has gone before; the happiness of supreme ecstasy ends in the supreme bitterness of sorrow.”

The tomb of Héloïse and Aberlard in Pere-Lachaise Cemetery. Photo: Marian Jones

You can still find traces of Héloïse and Abélard in Paris today. Stone carvings of them both adorn the house which now stands on the site where they lived, at 9-11, Quai aux Fleurs on the Île de la Cité and they are buried together in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. Visitors to Paris regularly seek out both these places, especially around St Valentine’s Day. But much more powerful than either is the story they left behind, a universal tale of love and loss, perhaps also one of betrayal. Their words, written nearly a millennium ago, will surely retain their emotive pull for generations to come. In that sense at least, their love will last forever.

Jean-Baptiste Goyet, Héloïse et Abelard, oil on copper, c. 1829.

Lead photo credit : Painting of Héloïse and Abélard. Musée d’arts de Nantes

More in history, Pere Lachaise cemetery