Americans in Paris: Elizabeth Blackwell, 1st Woman in America Awarded a Medical Degree

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell by Joseph Stanley Kozlowski, 1905. Syracuse University Medical School collection. Public domain.

In the early 19th century hundreds of Americans were inspired by a wave of enterprising, progressive and talented people who migrated to Paris, the cultural capital of Europe, then comprising four times the population of New York City. Most were well educated, reasonably well off and most, though not all, were young, single men. Arriving on the heels of the 1832 cholera epidemic, they found Paris a city of startling contrasts– wretched housing, appalling poverty and an ancient public hygiene system that carried raw sewage into gutters running down the middle of streets, juxtaposed against beautiful palaces, impressive bridges, sumptuous gardens, towering churches, fine art, avant-garde literature and sublime music. Baron Haussmann, the prodigious French civil servant hired by Napoléon III, would not commence his massive urban renewal projects until 1853. Into this maelstrom of convergent sensibilities, Elizabeth Blackwell arrived in Paris in the spring of 1849.

Elizabeth Blackwell was born on February 3, 1821 in Bristol, England, the third of nine children born into the wealthy, Protestant-Congregationalist family of Samuel Blackwell and Hannah Lane. (The Protestant-Congregationalists were supporters of social reform movements, including abolitionism, temperance, and women’s suffrage.) Samuel owned a prosperous sugar refinery and Hannah looked after her children and their country estate. Elizabeth was educated at home by private tutors, as were the rest of her siblings. Her parents believed that their children should be given the opportunity for unlimited development of their talents and gifts.

Following the loss of his sugar refinery in a fire, Samuel decided to take his family to live in America. In August 1832, the Blackwells embarked on a seven week voyage to New York. Once established, Samuel formed the Congress Sugar Refinery, and for the next six years the family lived and prospered. During this time Samuel became active in the growing abolitionist movement and the family attended anti-slavery rallies. Because the sugarcane industry used slave labor, Samuel sold his business and moved his family to the booming town of Cincinnati, Ohio in order to grow sugar beets. Sadly, just a few weeks after arriving in Cincinnati, he died of a fever leaving his family almost destitute.

Blackwell was commemorated on a U.S. postage stamp in 1974, designed by Joseph Stanley Kozlowski. Syracuse University Medical School collection. Public domain.

With the family’s survival at stake, Elizabeth, then age 17, and her older sisters, Anna and Marian, resolved to become self-sufficient, and started a school in their home – The Cincinnati English & French Academy for Young Ladies. With revenues from tuition, room and board, the school made enough money to keep the family going for the next four years. Introduced to the ideas of transcendentalism by her older sister, Anna, Elizabeth began attending the Unitarian Church and various religious services in other denominations (Quaker, Millerite, Jewish). But a conservative backlash from the Cincinnati community forced the academy to close in 1842. For the next two years Elizabeth and her sisters taught students privately.

In 1844 Elizabeth was invited to take a teaching job that paid $400 a year in Henderson, Kentucky. Although she was pleased, she was equally disturbed by her first encounters with the realities of slavery. “Kind as the people were to me personally, my sense of justice was continually outraged; and at the end of the first term of engagement I resigned the situation.” She returned to Cincinnati determined to find a more stimulating, productive and agreeable way to spend her life.

As often happens, when one door closes another opens, and while in Cincinnati, Elizabeth visited a close friend who was dying. She told her that her illness would have been more bearable if she had been treated by a woman, because she believed women had inherently compassionate natures. The idea that women would be more comfortable being examined and confiding their medical ailments to a woman doctor struck her like a thunderbolt. Even though she had always been physically repelled by diseases and ailments of the body, she decided then and there to overcome her aversions and become a doctor.

In order to raise the money to attend medical school, Elizabeth taught slave children at Sunday Schools in North and South Carolina between 1845 and 1847. While in N.C., she stayed with the Reverend John Dickson, who had been a physician before becoming a clergyman. He was extremely supportive and allowed her access to his medical books. Moving next to Charleston, S.C., she lodged with Dickson’s brother, Samuel, a prominent physician and professor of medicine, who also encouraged her to apply to several medical schools. Being a woman, she was rejected out of hand.

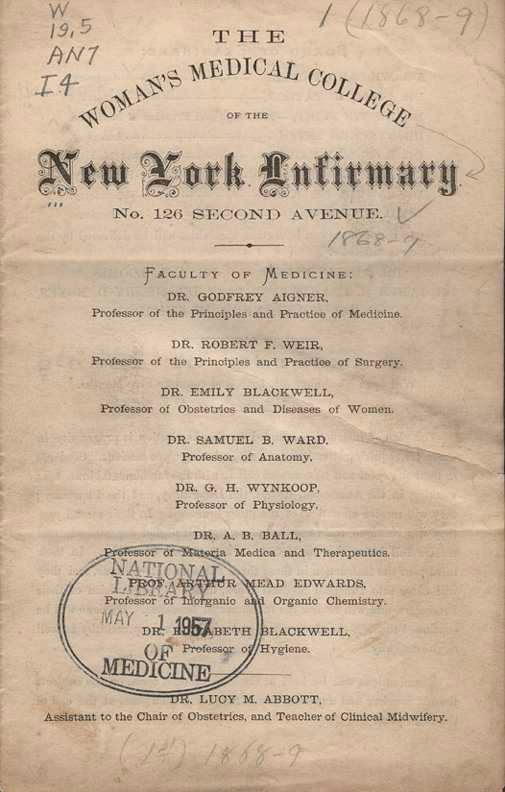

The Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary. [Announcement, 1868–69]. Public domain.

On January 23, 1849, at the age of 28, Elizabeth Blackwell graduated top in her class, becoming the first woman in America to be awarded a medical degree. Her ambition now was to become a surgeon. In April, Elizabeth decided to continue her studies in Europe. She visited a few clinics in England, then headed to Paris, at that time the world’s leading center of medicine and medical training. A total of 12 hospitals in Paris provided treatment for 65,935 patients. The largest and oldest of the hospitals, Hôtel-Dieu, was considered pre-eminent in surgery, the Hôpital de la Pitié was known for its clinical medicine, particularly for the treatment of tuberculosis, and the Hôpital des Enfants-Malades enjoyed the distinction of being the first children’s hospital in the world. The sheer numbers of patients and the range of their diseases gave medical students a first-hand experience they would not be able to obtain elsewhere.

Except, if you were a woman.

Elizabeth was allowed to enroll at La Maternité, the world’s leading maternity hospital, founded in 1795 at the ancient Abbey of Port-Royal, with the proviso the that she would be treated as a student midwife, not a physician, under the watchful eye of Sage-Femme, Madame Madeleine-Edmée Clémenatine Charrier. She also made the acquaintance of Hippolyte Blot, a young resident physician. She gained invaluable medical experience through Charrier’s and Blot’s mentorship and training. By the end of the year, Paul Dubois, the foremost obstetrician in his day, voiced his opinion that Elizabeth Blackwell would make the best obstetrician of either sex in the United States. Soon thereafter, while Elizabeth was treating an infant with purulent opthalmia, she contracted the disease, losing sight in one eye. All of her hopes of becoming a surgeon ended abruptly.

Undaunted, she returned to England, and enrolled at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London where she met Florence Nightingale. The two became close friends sharing a zeal for personal hygiene and preventative care – something many physicians overlooked at that time, neglecting to even wash their hands before treating patients.

In 1851 Elizabeth returned to New York, but nobody would employ her as a physician, so she set up her own practice. In 1853, she established The New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children. Four years later, she had raised enough funds from donors to open a hospital, The New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. The hospital soon gained a good reputation and became a training center for nurses. Although she never married, she adopted a seven-year-old Irish immigrant orphan, Katherine Berry – Kitty – who travelled with her and stayed with her for the rest of her life.

In 1858, Elizabeth became the first woman on the British Medical Register, which allowed her, finally, to practice there. In 1868 she founded a women’s medical college at the New York Infirmary. The college opened with 15 students and a faculty of nine, with her as Professor of Hygiene. Her sister Emily, who had also become a doctor, taught obstetrics. The college remained open until 1899, when Cornell University Medical School began accepting women students. Elizabeth returned to England permanently in 1869, establishing a large and successful practice in London. In 1875, she was awarded the Chair of Gynecology at the London School of Medicine for Women. Unfortunately, after only a year, her own ill health forced her to retire from both lecturing and medical practice.

Throughout her life, Elizabeth was a prolific author on health and social topics and continued writing into her retirement. Her works included Medicine and Morality (1881), Purchase of Women: the Great Economic Blunder (1887) and The Influence of Women in the Profession of Medicine (1890). At the age of 74 she published her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women.

Elizabeth Blackwell died of a stroke on May 31, 1910, age 89, at home in Hastings. In accordance with her wishes, her ashes were buried in the cemetery at St. Munn’s Parish Church in Kilmun, Scotland.

Elizabeth Blackwell, 1905. Courtesy of Blackwell Family Papers, Schlesinger Library. Photograph of an older Elizabeth Blackwell with her adopted daughter Kitty and two dogs, 1905. Public Domain

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell by Joseph Stanley Kozlowski, 1905. Syracuse University Medical School collection. Public domain.

More in Americans in paris

REPLY

REPLY