A brief History of the Louvre

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

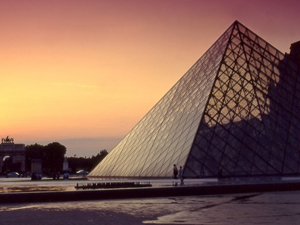

The beautiful Louvre Museum, or Musée du Louvre, is well-known world-wide for the art and artefacts showcased within it, and there are plenty of people around who will happily give you a list of their favourite paintings and other ‘hidden’ gems, when asked. The outdoor scenery is breath-taking, from the ornately chiselled angels on the museums exterior, to the glass pyramid, and even the picturesque scene it presents beside the Seine River.

The beautiful Louvre Museum, or Musée du Louvre, is well-known world-wide for the art and artefacts showcased within it, and there are plenty of people around who will happily give you a list of their favourite paintings and other ‘hidden’ gems, when asked. The outdoor scenery is breath-taking, from the ornately chiselled angels on the museums exterior, to the glass pyramid, and even the picturesque scene it presents beside the Seine River.

But there’s far more to this historic place than painting collections and artefacts which date back to as far as 11,000 years. Indeed, this building has seen plenty of action and dramas unfold around it and even in it, through the decades.

Origin Story

Most Francophiles likely already know this, but as a refresher and opening bid for those who don’t, the Louvre was commissioned by King Phillipe-Auguste in 1190 and it was originally designed as a fortress to protect the French from Viking raiders (they were a real concern back then). It certainly served its purpose, and almost 500 years later the French were still around and the Louvre was reconstructed to become a royal palace by King François I. Each successive monarch after him made their own mark on the building by adding and extending the Louvre’s grounds and grandeur.

This worked out fairly well for 100 years, until the Sun King and arts patron, Louis XIV, decided he’d had quite enough of the Louvre and moved his royal court and vast painting collections to Versailles. He preferred to reside in the Tuileries Palace which was nearby the Louvre while Versailles was completed. The Louvre became the home of artists, until 8th November 1793 when the French Revolutionary government turned the Grande Galerie of the Louvre into a fine-arts museum.

This worked out fairly well for 100 years, until the Sun King and arts patron, Louis XIV, decided he’d had quite enough of the Louvre and moved his royal court and vast painting collections to Versailles. He preferred to reside in the Tuileries Palace which was nearby the Louvre while Versailles was completed. The Louvre became the home of artists, until 8th November 1793 when the French Revolutionary government turned the Grande Galerie of the Louvre into a fine-arts museum.

In present times, only the Lower Hall (Salle Basse) has retained the original medieval interior. The glass-and-steel pyramid in the Napoleon courtyard (and it’s inverted below-ground counterpart) was added in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This artwork and functional entrance is, to me, a nod given to the still-present enchantment that the first-ever Egyptian collection wove on the French and other nationalities around the world when it debuted at the Louvre. The first Egyptian pieces included papyri, sarcophagi, and statues of deities such as Hathor and Sekhmet, which were displayed at the Louvre following Napoleons Egyptian Campaign.

Packed Up and Hidden

Today, it seems quite strange – almost sacrilegious – to think that there are people out there who’d resort to looting or destroying items in the Louvre, home to what many consider a culmination of human triumphs in the art world. However, let us face facts: humanity does not have the greatest track record at preserving historic items.

Which is why, preempting the outbreak of WWII on the 25th of August 1939 all Parisian museums closed. Art collections, statues, and other iconic items were packed up and rushed as far away from Paris as possible to try and protect them. Many important pieces from Compiègne museums and the Louvre, like the Venus de Milo, Mona Lisa, and Winged Victory of Nike, were taken into the French countryside, to castles, manors and châteaus, most notably to Château de Valençay and Château Chambord, as these buildings were less likely to be viewed as strategic targets in the war.

Which is why, preempting the outbreak of WWII on the 25th of August 1939 all Parisian museums closed. Art collections, statues, and other iconic items were packed up and rushed as far away from Paris as possible to try and protect them. Many important pieces from Compiègne museums and the Louvre, like the Venus de Milo, Mona Lisa, and Winged Victory of Nike, were taken into the French countryside, to castles, manors and châteaus, most notably to Château de Valençay and Château Chambord, as these buildings were less likely to be viewed as strategic targets in the war.

This was a good call as soon after WWII broke out, Nazi’s occupied the mainly empty museums, and in a strange twist, used the Louvre to house stolen artworks they’d ‘acquired’. The German authorities reopened the Louvre in the 1940s to try and breathe life into the predominantly deserted hallways and galleries, and to provide Nazi soldiers and others the chance to view the phantasmal appearance of the glamorous cultures the museums once housed.

The safely stowed away artworks and objects from the museums were safeguarded by many people, such as René Huyghe, the then curator of the Louvre, and the Duke of Sangan until the Liberation of France. After 1945, the artworks were returned to the museums they came from.

Haunted Hallways

This last fact is a little more unusual than the ones listed above, especially considering that ghosts are a touchy subject, with d’art, as well as 35,000 artworks, it could be likely some of them are haunted. Tales of strange spheres and shadows in the medieval section of the museum (Salle Basse) have been reported over the centuries – likely because the corbels and columns here date from around 1230.

It is also believed that ‘the little red ghost’ described in appearance as a gnome in red, is heralded as a harbinger of tragedy to France (though more often than not is said to give advice and make bargains with rulers). It is quoted by numerous sources as being seen originally by Catherine de Medici, and then later by Henry IV, Louis XVI, and Napoleon, and it is said that it is ‘often’ spotted between the nearby Tuileries and the Louvre.

Aside from the ghostly figures believed to have been seen above, there is a series of manipulated photographs titled “Les Fantomes du Louvre” or rather The Ghosts of the Louvre by Enki Bilal. These were displayed from December 2012 – March 2013 in the Louvre Museum.

Photo Credits:

Photo 1: Benh Lieu Song (Creative Commons)

Photo 2: Garnier circa 1667 (Creative Commons)

Photo 3: Musée des Archives nationales

Roseanna McBain is a writer for TravelGround.com. She enjoys learning about myths and legends from cultures around the world, attempting to recreate French cuisines, and enjoying the beautiful outdoors with her husband on weekends.

More in history, Louvre, Paris art museums