Albert Camus and the French-Algerian War

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

When it comes to revolutionary writers, the French have many claims to fame. Very few look as chic, handsome and, well, French, as the philosopher and novelist Albert Camus. He’s a kind of an international literary super-star, the James Dean of philosophy. Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy went so far as to make a huff about his remains being moved to the Panthéon- a breathtaking monument in Paris where Victor Hugo and Voltaire lie.

When it comes to revolutionary writers, the French have many claims to fame. Very few look as chic, handsome and, well, French, as the philosopher and novelist Albert Camus. He’s a kind of an international literary super-star, the James Dean of philosophy. Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy went so far as to make a huff about his remains being moved to the Panthéon- a breathtaking monument in Paris where Victor Hugo and Voltaire lie.

That never happened, and I’m pretty sure that in his request for the burial transfer, Sarkozy never mentioned the Algerian-born writer’s lifelong plight over the French-Algerian war. Just as Camus’s French-Algerian identity crisis is somehow omitted in contemporary discussion, so too is the bloody war over Algerian independence. But if we talk about Camus, we must talk about the French-Algerian war, and let’s face it, we must talk about Camus.

With the famous image of Camus along a dimly-lit Parisian street with a hand-rolled cigarette tucked between his lips and an asymmetrical coat collar framing his face, it is hard to image that he was almost 30 before ever coming to Paris. Upon arrival in France in 1940, he quickly fell into the intellectual scene thanks to his lyrical philosophy – part sensualist, part humanist, and highly comparable to Nietzschean prose. But despite his new fame, his heart was tied to the impoverished Algerian community. He never seized writing about Algeria and was one of the few to anticipate the discord that would sweep through Paris concerning the Algerian question. He knew a war was coming; he felt it for a long time. He didn’t know he would be alone in trying to prevent it.

“A Whole Race Born in the Sun and the Sea”

Before falling in and out of the Sartre-dominated intellectual roundtable at the jazz infused Café de Flore, and before his novel L’Etranger found him a spot among the highest echelon in the cannon of existential literature, Camus lived in the slums of Belcourt, a city in the south-eastern pocket of Algiers. As a boy who grew up in poverty amidst the olive trees along the Mediterranean, he found solace in the sun and the sea.

In a three-bedroom apartment without electricity, a bathroom, or running water, Camus lived with his mother, brother, uncle, and grandmother. His father died when Camus was an infant, and his mother, illiterate and deaf, supported the family by cleaning the seaside homes of well-off European settlers. They belonged to the working class which constituted 80 percent of the European inhabitants of Algeria known as pied noirs.

In this poor corner of Algiers, the indigenous-Algerians, Muslims from various origins including Kabyle, Turkish, and Arab, and French-Algerians were commonly and inoffensively shuffled together, creating a relatively pluralistic atmosphere. Here “Frenchmen” and “Arabs” lived in harmony, and Camus saw little difference in their economic status. As far as he was concerned, his family oppressed no one, and no one oppressed them.

But the love that Camus shared “with a whole race born in the sun and the sea” could not eclipse the injustices and uncertainties that colonialism invariably fosters. When the French colonized Algeria in 1830, the Muslim population was politically and economically marginalized. The French stripped the indigenous Algerians of any important role in the government and denied them French citizenship. As the French made vast improvements to Algeria, turning barren soil into rich farmland, igniting the Algerian wine industry, and building roads and railways, they felt increasingly justified in arrogating the right to rule, and Algeria was eventually annexed. But as Algeria became more French, Muslims were becoming less included in French society. Muslims received paltry wages, had little to no voting power, and received less education than Europeans. The inequality was blatant and the discontent mounting.

In 1937 Camus took up a job at the Alger-Républicain, a socialist newspaper concerned with and directed to the Muslim and lower class populations, and the horrors of colonialism were finally unveiled. In an 11-part series for the paper, Camus disclosed the inhumane living conditions he witnessed in the predominantly-Muslim region of Kabylia. Gripped by the starving children he saw in the streets scavenging for food in a sea of rags and decay, he began lashing out at the French government and reprimanding colonialism. In a fit of empathy redolent of Dostoevsky, he said, “Perhaps we cannot prevent this world from being a world in which children are tortured. But we can reduce the number of tortured children.” Hence be began a lifelong Literary-liaison with the poor of Algeria and a personal crusade for human rights, justice, and equality.

The War of Two Peoples

The War of Two Peoples

The simple truth about the French-Algerian war is that the Algerian Muslims lost their patience and the French lost their chance. Before the outbreak of war, native-Algerians modestly called for more autonomy, asking for citizenship, religious freedom, and equality in education and work. But the French, particularly the French pied noirs, were afraid of losing their stronghold in the region and wouldn’t budge until it was too late. After rigged elections denied Muslims weight in Algerian politics and the French were defeated in Indochina, Muslim nationalist movements began forming, eventually culminating in the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN). The FLN launched its fight for independence with an armed revolt on All Saints’ Day in 1954.

From Paris, Camus heard of the Muslim populations in Algeria rallying against French rule, and he read about the brutal massacre of Europeans at the hands of Muslims in Sétif. The FLN was calling for the removal of Europeans from Algeria. Camus’s Algiers, the sanguine and sunburnt city by the sea, was giving way to volatility and turmoil. The war escalated, and with it, the massacre of civilians in Algeria and Paris. Pied Noir families, not unlike Camus’s, were the first to be mowed down by FLN gunmen while sunbathing and swimming along the Algerian coast. The French government responded two fold by disproportionate attacks on Muslims and the use of torture on suspected terrorists. Lasting from 1954 to 1962, this would be the most severe and bloody colonial war.

The Only Pacifist in Paris

As passion and nationalism triumphed and an ideological fissure emerged between those for Algerian independence and those against it, Camus found himself in no man’s land. The Parisian intellectuals voiced mainly by Jean-Paul Sartre sided with the call for Algerian independence while the French government and pied noirs stood in grave opposition to it. As the most famous French-Algerian intellectual, all eyes were on Camus.

But he would not stand with either camp. He denounced the “reign of terror” on both sides and couldn’t understand the “insane admiration of force.” No, he would not endorse the bombs, the torture, or the murder of women and children, even if it was in the name of a confused idea of freedom. Neither Algerian independence nor French dominance was worth innocent bloodshed. “I cannot believe that everything must be subordinated to a single end. There are means that cannot be excused. And I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice. I don’t want just any greatness for it, particularly a greatness born of blood and falsehood. I want to keep it alive by keeping justice alive,” he wrote in a short essay about war.

Camus could not concede that over a million innocent Europeans – including his handicapped mother – must flee the only home they had ever known. The Europeans had been rooted in Algeria for over a century. Besides, what was Camus without the sun and the sea he had so ardently wrote about all his life? “I have passionately loved this land where I was born, I drew from it whatever I am, and in forming friendships I have never made any distinction among the men who live here, whatever their race,” he said in defense of his right to Algeria. On the other hand, after all his calls for reform, how could Camus support French colonialism and oppression? He was the first to voice the suffering of the Muslims and knew first had the injustices the French government was guilty of. But just as he knew that Muslims in Algeria were forced into destitution by the French, he also realized that complete French withdraw would lead to further Algerian poverty and strife.

Virtually alone and amidst the whirling of bullets and radicalism, Camus called for pacification and peace talks. In 1955 he wrote articles for L’Express and Algerian Community begging for a rational and levelheaded discussion about the future of Algeria. In Letter to an Algerian Militant, published shortly after the massacre of 100 Europeans at Philippeville by the FLN, Camus condemned violence as immature and misguided. When his articles appeared too modest, he made a stronger attempt at diplomacy and held a conference in Algiers calling for a civilian truce. Several thousand French-Algerians and Muslims crowded into the Cercle du Progrès to hear Camus call on the French government and the FLN to halt all attacks on civilians. “We can propose, without making any change in the present situation, that we refrain from what makes it unforgivable – the murder of the innocent,” he said as protestors outside showered the windows with pebbles and chanted “death to Camus.”

His pleas went unheard and the world branded his vision idealistic and obsolete. The clock on French-Algerian relations could not be reset. Camus was no Gandhi, and eventually people stopped listening to him and he stopped talking. For years he was completely silent despite the worsening of the war. Ashamed that he could not prevent his beloved homeland from becoming a battle ground, he sank into depression. Only once more did he publish anything on the matter. In 1958, a collection of his work called Algerian Reports was introduced with a new preface asserting his stance: Algeria should remain connected to France in order to be economically viable but with equality for all. His theme of justice and pacification reverberated once more: “Even those who are fed up with morality ought to realize that it is better to suffer certain injustices than to commit them even to win wars, and that such deeds do us more harm than a hundred underground forces on the enemy’s side.” Without any closure or consolation on Algeria, Albert Camus died in a car accident two years later at the age of 46.

The Record of a Failure

The French and the FLN finally reached a ceasefire in 1962 and Algeria became independent. It is hard to know exactly how many people died in the war but some estimates reach over 500,000. The war resulted in the fall of the Fourth Republic and contributed to the demise of six prime ministers. Some two million Algerian inhabitants were forced to leave Algeria to come to France and, having nowhere to live or work, sank further into poverty. The FLN would later be criticized for becoming authoritarian and splinter factions were question its validity for years to come. After the brutal Algerian civil war in the 90’s, it is obvious that Camus had profound foresight about the instability that would ensue after French withdraw.

Camus regarded his inability to save French-Algeria as his ultimate failure. Today, French-Algerian relations remain strained. Nicolas Sarkozy angered Algerians when he refused to apologize for French colonialism and France’s role in the war. Despite current French President Francois Hollande’s sympathy towards Algeria and his pledge to reverse French intransigence, France was still excluded from the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence last July.

Camus regarded his inability to save French-Algeria as his ultimate failure. Today, French-Algerian relations remain strained. Nicolas Sarkozy angered Algerians when he refused to apologize for French colonialism and France’s role in the war. Despite current French President Francois Hollande’s sympathy towards Algeria and his pledge to reverse French intransigence, France was still excluded from the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence last July.

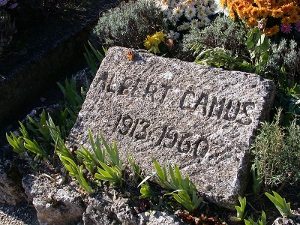

A small French-Algerian War Memorial can be found along the Seine river walkway between the Eiffel Tower and the Notre Dame. Albert Camus is buried in a humble cemetery in the Provencal village of Lourmarin.

photo 1 by New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, where the New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection considers all of its photographs public domain [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

photo 2 by New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

photo 3 [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia commons

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

We update our daily selections, including the newest available with an Amazon.com pre-release discount of 30% or more. Find them by starting here at the back of the Travel section, then work backwards page by page in sections that interest you.

Current favorites, including bestselling Roger&Gallet unisex fragrance Extra Vieielle Jean-Marie Farina….please click on an image for details.

Click on this banner to link to Amazon.com & your purchases support our site….merci!

More in Camus, French history, history

REPLY