Un Enfant de Toi (Me, You, and Us): Hell Is Other Lovers

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

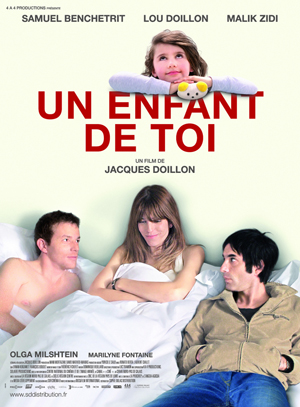

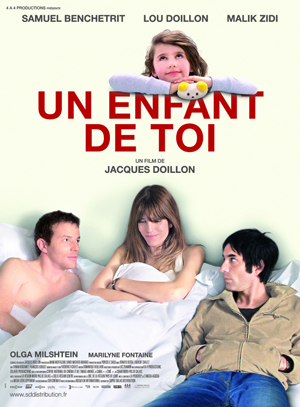

Jacques Doillon’s films are unique in the intimiste genre in that they often involve children in the action, and Un Enfant de Toi (Me, You, and Us) is no exception. In fact, Olga Milshstein as seven-year-old Lina is what makes this two-and-a-quarter hour story of a separated couple that can’t stay apart so absorbing. Lina’s mother Aya (Lou Doillon) works for a museum, her father Louis (Samuel Benchetrit) is an instructor. As with many separated couples, their child keeps them in contact. For much of the film Aya and Louis can be hard to take, two self-centered Parisian bobos whose complicity with each other is a substitute for real intimacy. We imagine the egoisme à deux that they had when they were married and understand why they can’t bear to be separated—they reinforce each other’s narcissism.

Jacques Doillon’s films are unique in the intimiste genre in that they often involve children in the action, and Un Enfant de Toi (Me, You, and Us) is no exception. In fact, Olga Milshstein as seven-year-old Lina is what makes this two-and-a-quarter hour story of a separated couple that can’t stay apart so absorbing. Lina’s mother Aya (Lou Doillon) works for a museum, her father Louis (Samuel Benchetrit) is an instructor. As with many separated couples, their child keeps them in contact. For much of the film Aya and Louis can be hard to take, two self-centered Parisian bobos whose complicity with each other is a substitute for real intimacy. We imagine the egoisme à deux that they had when they were married and understand why they can’t bear to be separated—they reinforce each other’s narcissism.

What complicates things is that both characters have formed new couples. Aya is living with a well-to-do dentist named Victor, while Louis is seeing Gaëlle, a young student (presumably one of his). The newly reconstituted couples seem more problematic than the broken marriage: Aya is diametrically opposed to Victor, who manages the feat of being both bland and prickly, while Gaëlle is too young and natural for narcissist-in-chief Louis.

As for Lina, she’s such a cute kid we might think she merely serves as sentimental relief. But she’s the catalyst, or at least accelerator, of much of the action. Precocity doesn’t stand in the way of mischief, as when she steals her mother’s ring so she can “marry” two of her school friends, or when she not-quite-innocently tells Victor that Mom was sleeping at Dad’s. If Lina is what holds her parents together, the real catalyst is another child, an unborn one: the child Aya wants to have with Victor—or maybe with Louis. Or maybe not at all. Just the possibility of a child (another child) shakes everyone out of their irresponsible bobo redoubt (though with the exception of Gaëlle, age is also sneaking up on them).

The movie is a kind of variation on Jules and Jim, François Truffaut’s classic about a ménage à trois that works, joyously and comically. But there’s not much joy or comedy in Un Enfant. On one level, the film captures today’s complex-ridden relationships. On another it’s quite conservative: the once-married pair really belong together, and are miserable being with others. It’s not much different from many Hollywood melodramas and screwball comedies of the thirties.

The movie is a kind of variation on Jules and Jim, François Truffaut’s classic about a ménage à trois that works, joyously and comically. But there’s not much joy or comedy in Un Enfant. On one level, the film captures today’s complex-ridden relationships. On another it’s quite conservative: the once-married pair really belong together, and are miserable being with others. It’s not much different from many Hollywood melodramas and screwball comedies of the thirties.

Un Enfant also resembles the films of John Cassavetes, in the intimate subject, and the way it’s filmed. Doillon sometimes shoots in a slightly jittery hand-held style, with lots of close-ups. The acting brings to mind Cassevetes-style improvisation. Doillon, like Cassavetes, achieves moments of raw emotion, but improvisation has its downside: in Cassavetes’ films it’s characters meandering off on endless tangents. In Un Enfant, the actors often seem to be mugging for the camera. Lou Doillon in particular seems too obviously acting in front of her director father Jacques.

Still, the movie is mostly enjoyable as a showcase for a quintet of acting styles. Lou Doillon (who’s the half-sister of Charlotte Gainsbourg) has the sultry, unstable presence of a young Julie Christie, while Samuel Benchetrit is all live-wire rakish charm. Malik Zidi as Victor does a good job making his unenviable dentist a worthy antagonist. Marilyne Fontaine as Gaëlle also does a good job with not much to work with. The most charismatic player is little Olga Milshstein, who gives an astonishing performance, even though the director plays up the precociousness until she’s as cute as a baby seal (which can make the viewer channel his inner Eskimo hunter).

Still, the movie is mostly enjoyable as a showcase for a quintet of acting styles. Lou Doillon (who’s the half-sister of Charlotte Gainsbourg) has the sultry, unstable presence of a young Julie Christie, while Samuel Benchetrit is all live-wire rakish charm. Malik Zidi as Victor does a good job making his unenviable dentist a worthy antagonist. Marilyne Fontaine as Gaëlle also does a good job with not much to work with. The most charismatic player is little Olga Milshstein, who gives an astonishing performance, even though the director plays up the precociousness until she’s as cute as a baby seal (which can make the viewer channel his inner Eskimo hunter).

While Jacques Doillon has an effortless mastery over his medium, his direction is less than satisfactory. That’s more a question of concept than technique. Though there are plenty of outdoor scenes, nicely shot, Un Enfant feels like a chamber piece. There are no real characters outside of the two couples and Lina. We see Victor in his dentist’s office, but no patients or employees. Likewise, there are glimpses of Aya hanging paintings, but she gives only nodding recognition to co-workers. We never see Louis or Gaëlle at work or school. This concentration makes for intensity, but of a very claustrophobic sort.

Un Enfant is divided into three parts, actually labelled Part I, etc., with the obligatory epigraph. It’s an indication of the literary quality of the movie, which is very written and dialogue-heavy. That makes it refreshingly adult—for a while. The audience gets its second wind for Part II, but then its heart sinks when that’s followed by Part III. Yet that’s also when the characters’ puerile antics get most interesting, and we see some point in the pointlessness.

Un Enfant is divided into three parts, actually labelled Part I, etc., with the obligatory epigraph. It’s an indication of the literary quality of the movie, which is very written and dialogue-heavy. That makes it refreshingly adult—for a while. The audience gets its second wind for Part II, but then its heart sinks when that’s followed by Part III. Yet that’s also when the characters’ puerile antics get most interesting, and we see some point in the pointlessness.

Is there an end to all this denial of maturity? Louis tells Aya, in the understatement of recent film history, “I was too frivolous the first time.” But even as he’s says this, the (momentarily) re-reconstituted family is on the beach, heading for the waves … in their clothes.

Production: 4 à 4 Productions

Distribution: Sophie Dulac Distribution

More in film review, french cinema, French film, Paris film