L’Empereur de Paris: The Return of Vidocq

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Who was Vidocq? Many cultures have legendary criminal heroes: America has the Western outlaw and Al Capone, Latin America the drug lord, Britain has Robin Hood, Japan the yakuza gangster, Greece the 19th century klephts. For the French it’s Eugène François Vidocq (usually referred to simply as Vidocq). He was a larger-than-life character who led an amazing life stretching from the end of the 18th century to the middle of the 19th. He was a criminal but later became an informer and then a law-enforcement chief. And much more: pioneering criminologist, private detective, entrepreneur, author of memoirs.

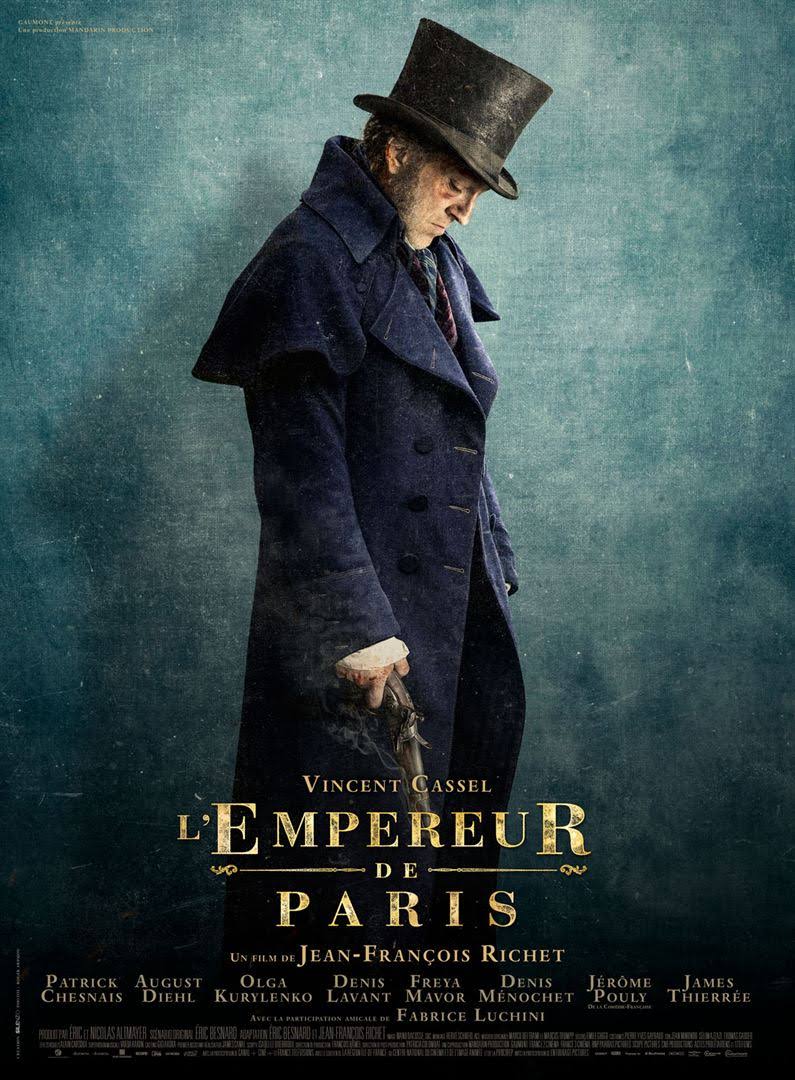

There have been many books (by Balzac, Dumas, Eugéne Sue) inspired by his life. Edgar Allen Poe’s Auguste Dupin, the first fictional detective, may have been based on him. There have been movies (French and even American) about him, as well as TV series. The latest Vidocq opus is a curious historical saga, L’Empereur de Paris (The Emperor of Paris), directed by Jean-François Richet and starring one of France’s most prominent actors, Vincent Cassel. (He played another criminal icon, Jacques Mesrine, in a two-part movie also directed by Richet.)

Photo: L’Empereur de Paris Youtube trailer

The film works as slam-bang entertainment, less so artistically—it’s a mostly classical hodge-podge—but at the same time it’s surprisingly cogent about its political themes. And in a not so subtle way the director may be making a trenchant commentary on the world of today.

L’Empereur de Paris starts with the gruesome killing of a rat (unconscionable if it was real, though as someone who once helped de-mouse a friend’s flat I’m in no position to judge). That sets the tone for the director’s harsh vision. We promptly go to a prison ship where Vidocq and other convicts are packed like, well, rats, and meet characters who will figure in later. Vidocq escapes and embarks on a trail of revenge, then paradoxically attempts to both get his criminal career back in gear and obtain a pardon, achieving some sort of redemption.

“L’Empereur de Paris”

Richet clearly modeled his film on Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York. There’s the same meticulous recreation of the lower depths of the big city. There’s also the same attention to period costumes, aiming at a sort of stylish shabbiness—Cassel/Vidocq reminds us of Daniel Day-Lewis in Scorsese’s film with his rakish top-hat. The director stages many acrobatic fights with fists, feet, clubs, knives and other weapons. It keeps the audience on edge, but eventually becomes tiresome, not to mention tiring, given the two-hour plus length of the film. How much fighting can there be in one film? (A lot.)

The acting is more entertaining. Vincent Cassel is always riveting, though he acts on a single note as Vidocq: grimly determined. The real Vidocq was that but much more. He was a busy ladies man, a brilliant figure who innovated criminology techniques, someone who dealt with a wide variety of high-life as well as low-life personalities. Among the other vivid performances by a large cast, the best by far is Fabrice Luchini’s turn as the Minister of Police, Joseph Fouché. Denis Lavant is excellent as the scheming criminal Maillard, as is Patrick Chesnais as a police official. The rather conventional love interest is serviceably played by Freyor Mavor, who has the scrubbed milk-maid looks of a young Isabelle Huppert along with the sensuous full features of Béatrice Dalle, but is actually British.

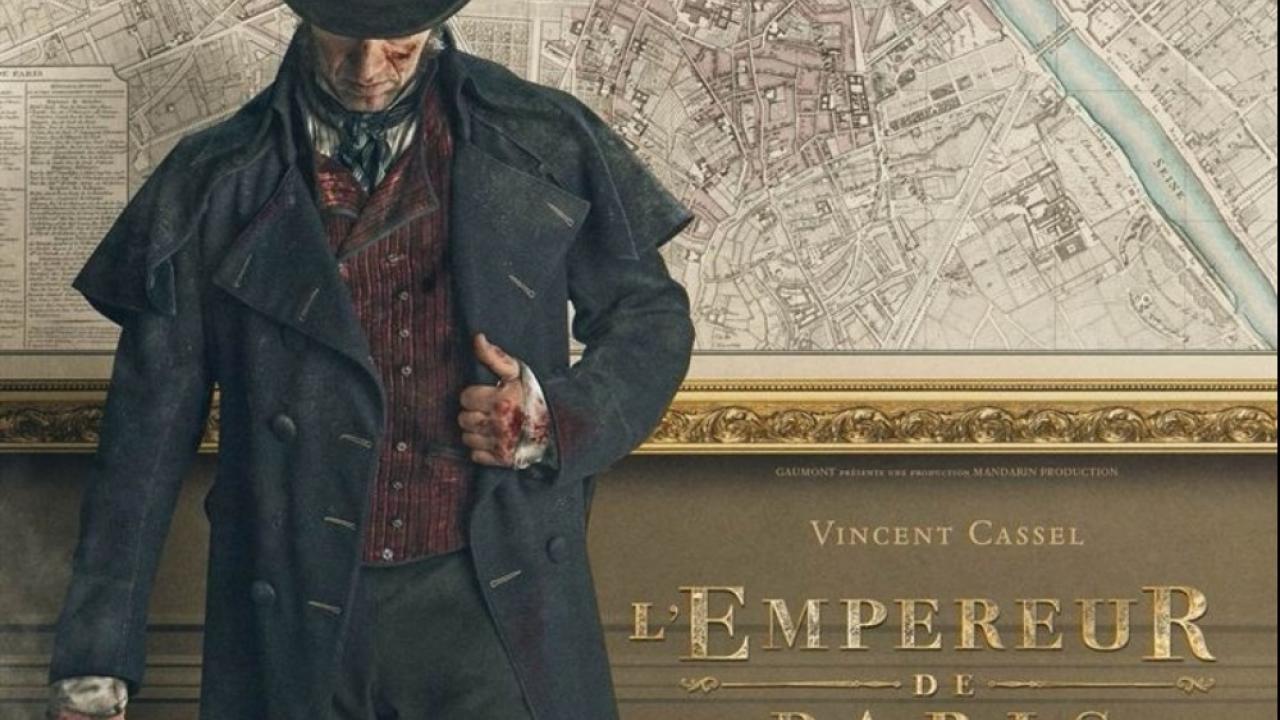

Photo: L’Empereur de Paris Youtube trailer

It’s a shame the production and acting don’t serve a more worthy script. Instead of dramatizing Vidocq’s progress from master crook to master snitch and then to head of a police unit we get B-movie melodrama and gobs of blood and gore. In Richet’s version of the story, Vidocq pursues criminals with the help of a nobleman-soldier, the Duc de Neufchâteau (James Thierrée), and is caught up in ferocious battle with gang kingpins Maillard (Lavant) and Nathanael de Wenger (August Diehl). He’s helped by his prostitute companion Annette (Mavor), and at the same time angles for his pardon, aided by apparently platonic friend Baronne de Giverny (played by a sultry Ukrainian actress, Olga Kurylenko). He gets his pardon at the end, but at a steep price. Bof.

“L’Empereur de Paris”

Fortunately there’s more to L’Empereur de Paris than that. The writer Joan Didion, commenting on Costa-Gavras’ film about Chile, Missing, said that the background story (the detailed depiction of Pinochet’s dictatorship) was more significant than the foreground story. This is also true of Richet’s film. He captures the mood of France under the Empire, after the collapse of both the centuries-old monarchy and the democratic promise of the Revolution. The upper classes show off their busts of Napoleon, while the lower shout “Vive l’Empereur” and sing militaristic songs at every opportunity. Men (including Napoleon himself) went off to war—the ethos of Empire—and returned home with an arrogant bearing. Soldiers imposed order in the unruly capital more brutally than under the old order. The soldiers of the underworld, with its own brutal overlords, were but a reflection of the new order.

One can’t help but feel echoes of present-day Europe (and elsewhere). Established orders have fallen, upstart outsiders have taken their place. With both tradition and genuine democracy gone by the wayside, the vacuum attracts money-making, power-chasing and violence. Where does it end? The most powerful figure depicted in L’Empereur de Paris, the ruthless Fouché, was eventually tried for his part in the death of Louis XVI, after the pendulum swung back to monarchy. We all know what happened to Napoleon.

Production: Mandarin Cinéma/Gaumont/France 2 Cinéma/France 3 Cinéma

Distribution: Gaumont Distribution/Athena Films

Lead photo credit : Photo: L'Empereur de Paris Youtube trailer