Viva Varda! La Cinémathèque Française Shines a Light on Agnes Varda

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Quirky, innovative, socially engaged, a feminist trailblazer – can one exhibition sum up Agnès Varda’s 70-year career in film and photography? There’s an intriguing poster outside the Cinémathèque Française in Bercy, where Viva Varda! is running until January 28th. A young Agnès sits demurely, hands folded in her lap, looking wryly upwards, as if pausing from filming to reflect on life’s idiosyncrasies. She is photographed in black and white, a nod to the 1950s when she started her career, but set against a cheerful background of swirling shapes in bright blue, fluorescent pink and jaunty orange.

Inside, at the exhibition’s entrance, is another poster, of a much older Agnès, with her trademark plum-colored bob, thumbing her nose as if to say “I do what interests me. I hope you like it, but if you don’t, I’ll do it anyway.” The first film clip on show inside shows her struggling cheerfully down a 1950s Paris street, laden with photographic equipment. It captures her determination to take pictures, whatever the difficulties. If you didn’t already know that Varda was one of the few women of her generation to make a career in photography and film, these images mean you wouldn’t be surprised to hear it. It’s fitting then, that she is the subject of the Cinémathèque’s first ever exhibition devoted to a female filmmaker.

Agnès Varda Exhibition. Photo: Marian Jones

Agnès, who was born Arlette, changed her name as soon as she was 18, an early sign that she intended to do things her own way. Still in her 20’s, she installed a dark room in her home in Rue Daguerre – and later a makeshift film studio – and began filming La Pointe Courte, despite not having been to film school or worked on any films as an assistant. She set up her own production company, Ciné-Tamaris, another daring move for such a novice, and, on a tiny budget, made this experimental piece. It combined the story of a couple who’ve reached a crisis point in their relationship with documentary footage showing the plight of poor fishermen in the southern French town of Sète. People, above everything else, were her subject.

A whole section of the exhibition is devoted to what Varda called “cinécriture,” her radical approach to filming which brought her early critical acclaim. Before the French New Wave in cinema really took off, Varda was pioneering the techniques for which it would be known. She left the studio to film outdoors, used novice or amateur actors, portrayed strong female characters and above all saw the filmmaker as the “author” of the film in every sense. She wrote the script, then filmed and directed the piece. Until this point, women’s role in films had been largely limited to acting, but Agnès claimed much more control over the whole process.

She made over 40 films, many of them referenced in the exhibition, for example Cléo, from 5 to 7, made in 1962. It shows, more or less in real time, the two hours when Cléo is waiting for the results of a medical test and fills her time in various low-key ways. She walks through Paris, meets a friend, buys a hat, takes a taxi ride and the focus is always on her, rather than on the way she is seen by others. The critic André Bazin praised the “total freedom” of Varda’s style which, he said, made her the “auteur” of the work, exactly the effect she had wanted. Varda explained that “the film hit like a cannonball,” because she was a young woman with no experience of making films and that was so unusual.

Agnès Varda Exhibition. Photo: Marian Jones

Thematically too, Varda followed her own instincts and social commentary was a strong thread running through her work. In 1957 she accepted an invitation to visit China, then almost entirely closed to foreigners, and spent two months taking thousands of photographs which gave a detailed and insightful portrait of that little-known country. Also in the exhibition is material from Salut les Cubains, the project resulting from her visit to post-revolutionary Cuba in 1963. She took arresting, close-up photos of many, many Cubans and the resulting photo-montage is a pictorial love letter to that colorful country and its people.

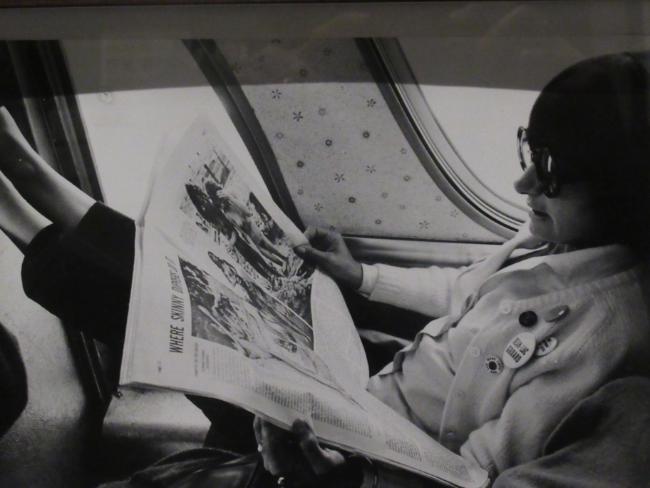

By 1967, Varda was in California, documenting the social upheaval and the protests of the anti-Vietnam war generation. Her photograph titled “Love-In” captured the hippie movement perfectly. Varda also photographed the poorer areas and documented the struggles for civil rights and the Black Power movement. Again, she was equally captivated by the people and by the politics. She showed great interest in the street art she found in America, undeterred by its sometimes gritty themes because, she said, art should not be confined to museums.

In the 1970s came a new project, Daguerrotypes, for which she made a record of Rue Daguerre, where she lived for seven decades. Again, interested in everything and in showing how things really were, she filmed the inhabitants and shopkeepers engaged in their daily lives. To watch it is to experience life in one little corner of the 14th arrondissement in 1975. In 2000, she made Gleaners, another study of everyday lives, but filmed this time in the French countryside. Was she trying to convey a message? She spoke of the “poetry of everyday gestures,” and explained her aim as being “not to show, but to make you want to see.” Varda wasn’t didactic. She left her audience to draw their own conclusions.

Agnès Varda Exhibition. Photo: Marian Jones

In 2017, at the age of 88, Varda set off around France with the artist JR, who was more than 50 years her junior, on a joint project called Faces, Places. They visited rural communities and factories, creating portraits of the people they met and shooting a documentary film. The project was described by critics as “New Wave meets the Instagram generation.” This “unique cross-generational portrait of life in rural France” won the Golden Eye award for documentaries at the Cannes Film Festival. Also featured in the exhibition is her 2008 Beaches of Agnès, the charming documentary she filmed to celebrate her 80th birthday. Her reminiscences are filmed in her unique style, merging stills and collages with film footage of places from her past. The result was an autobiographical and very personal “cinema essay.”

The last section of the exhibition is devoted to a topic which ran through the whole of her life: feminism. It can be seen explicitly in her work, for example in her 1977 film One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, which centered on women’s right to abortion. More generally, her creation of strong female characters and her focus on the female point of view stood out, especially before the sexual revolution arrived in France. Equally impactful was her status as one of the few women of her generation to succeed in film-making. All these factors combined to make her a figurehead for the feminist movement at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, where she joined Cate Blanchett and 80 other women in the 50/50 campaign to protest against discrimination in the film industry. This footage closes the exhibition.

Agnès Varda exhibition. Photo: Marian Jones

Agnès Varda once said that she simply wanted to “live and work on my own terms.” She refused to take herself too seriously – calling herself “The Dinosaur of the French New Wave” – but her devotion to her work was absolute. She filmed and photographed the subjects which interested her, showing a social conscience and a deep interest in people of every age and background. She pioneered new cinematic techniques which inspired generations of film-makers who came after her. You can ponder all this while smiling at the last cartoon images of her, clapboard in hand, announcing the end of the exhibition.

When Martin Scorsese heard of Agnès Varda’s death in 2019, he wrote: “Every single one of her remarkable handmade pictures, so beautifully balanced between documentary and fiction, is like no one else’s—every image, every cut… What a body of work she left behind.” This exhibition is the most fitting of tributes to her.

DETAILS

Viva Varda!

At the Cinémathèque Française

51, Rue de Bercy

Until January 28th, 2024

Entry 12 €

Concessions 9.50 €

Agnès Varda in New York. Exhibit photo: Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Agnès Varda exhibit. Photo: Marian Jones

More in Agnes Varda, cinema