Paris-Based Artist and Filmmaker Vincent Gagliostro: Of AIDS and Art

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It is probably impossible for those of us who are not gay and who did not even know we knew anyone who was gay in the 1980s when the AIDS epidemic was at its most frightening, to truly understand what it was like to live in that world. What must it have been like to lose two, three, four, or even more friends and loved ones a week to a raging epidemic no one yet understood and for which there was no treatment, and the progression of which was ravaging in its speed and intensity? What must it have been like not to know whether you would be the next one to contract the disease and that what you were seeing might soon be your own future? And what must it have been like to have to scream about the needs of your community and the need for action – for drugs and treatments and compassion and understanding – and be met with indifference?

Enraging and terrifying are the words that come to mind.

Artist and filmmaker Vincent Gagliostro (a contributing cinematographer for the Oscar-nominated documentary, How to Survive a Plague) lived in that world, and to this day, he can hardly speak of the losses. But he can make movies, and that is what led him to co-write and direct his first feature film, After Louie.

In the movie, award-winning British actor Alan Cumming puts in a powerful performance as Sam Cooper, a disillusioned and aging artist. Sam is also a former AIDS activist who served on the frontlines of ACT UP – the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power – the international advocacy group founded in 1987 to push the indifferent political and medical communities for legislation, medical research and treatment, and policies to fight the disease and bring an end to the suffering and loss of life.

In the movie, award-winning British actor Alan Cumming puts in a powerful performance as Sam Cooper, a disillusioned and aging artist. Sam is also a former AIDS activist who served on the frontlines of ACT UP – the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power – the international advocacy group founded in 1987 to push the indifferent political and medical communities for legislation, medical research and treatment, and policies to fight the disease and bring an end to the suffering and loss of life.

But that was then, and this is now, and Sam has grown bitter toward young gays who have little if any understanding of what gays of his generation went through that eventually enabled younger generations of gays to live open, accepted, healthy lives. He wants them to understand, and to at least feel some appreciation of and gratitude toward, those who had been on the frontlines of the long and difficult struggle.

Gagliostro uses Sam’s relationship with a younger gay man, Braeden, played sensitively by Zachary Booth, whom he picks up in a bar, to explore the different worlds in which gays of their respective generations live. Unbeknownst to Sam, Braeden is in a relationship with another man, and one who is HIV-positive, at that. When Sam learns of this, Braeden says it’s “no big deal.” No big deal to him, because today there are medications that keep the disease in check, but something that would almost surely have been a death sentence in Sam’s generation.

Ultimately, as Gagliostro has explained, the film is “an exploration of displacement, aging and being young,” and how succeeding generations are gay in ways different from those who were on the firing line of the gay movement, as encapsulated in the characters of Sam and Braeden.

Gagliostro has the bona fides to direct this film with authority. He not only talks the talk about issues related to being gay, but he walked the walk. At age fifteen he marched in the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade in New York City, and he was a founding member of ACT UP. He chaired its Outreach Committee, and New York magazine called him one of the six most influential players in the gay community of the time. As part of his activism, he designed some of the graphic art used by ACT UP to get the message across.

And parts of the movie are, of course, autobiographical. For example, Gagliostro shares Sam’s feelings about the intergenerational divide among gays. And in one particularly poignant scene, the names of all his friends and lovers who have died from AIDS that Sam scrawls on his living room wall are, indeed, the names of Gagliostro’s friends and lovers.

Most of us do not give much thought to the courage and desperation gays felt who were on the frontlines of that fight. But one clinical psychologist explains that it was “an extraordinary trauma” and compares it to “a wartime experience,” which brings to mind PTSD – post-traumatic stress disorder – because, let’s face it, the military battlefield isn’t the only place battles are fought.

In that respect, “After Louie” offers valuable insights – for everyone – into a time and world the difficulties of which must be acknowledged, validated, and understood.

While the movie has been making the rounds of film festivals, where it has been well received, and discussions are underway for broader release, the Galerie NeC nilsson and chiglien, at 117 rue Vielle du Temple in the Marais in Paris, owned by Roger Nilsson and Alain Chiglien, is holding its fourth and latest exhibition of Gagliostro’s artwork.

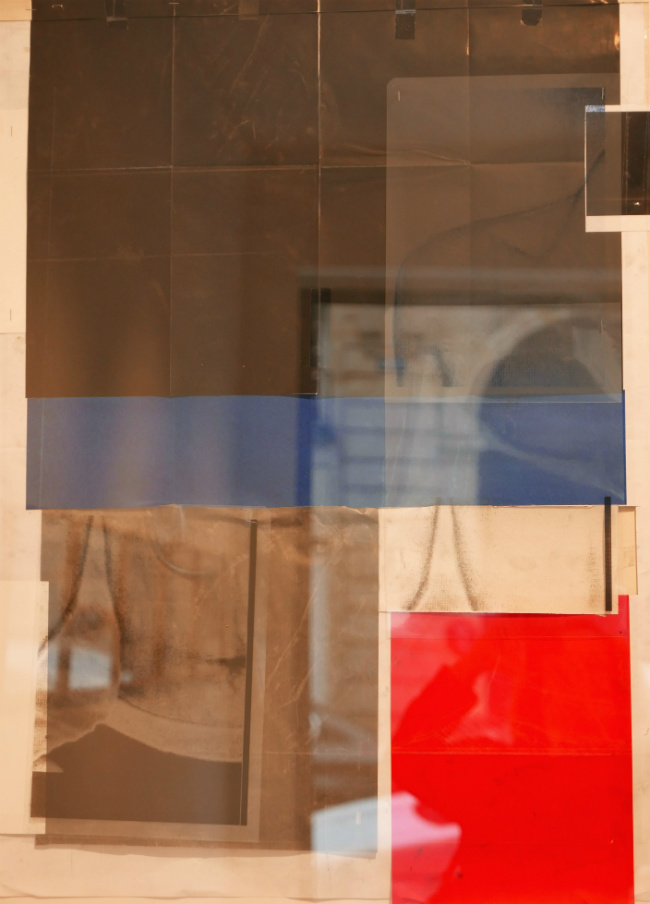

Vincent Gagliostro, Composition Picture 2, 2017-2018, ©Vincent Gagliostro / photo by Diane Stamm

Gagliostro has been making art for decades. He had his first solo show in 1976 in Washington, DC, and his first exhibition in Europe in 1997. Since 2005, he has been living in Paris with his partner, Richard Nahem, founder of the popular website, Eye Prefer Paris. Galerie NeC has been showing Gagliostro’s work for over ten years.

Gagliostro’s films and art are inextricably intertwined and demonstrate the organic way in which art evolves, in that Gagliostro uses his art as a kind of storyboard to explore what his next film might be. Galerie NeC held two shows of Gagliostro’s work on his art related to After Louie, and as gallery co-owner Roger Nilsson explained, the current exhibition, “Audition / 6:40 AM,” “is the beginning of a new film… [It] is Vincent’s way of conceptualizing the film before working on it.”

In this show are mixed media pieces, photographs, collages, and videos that, as Nilsson explains, explore the artist as predator, for that is how Gagliostro thinks of himself. “Vincent considers himself the artist as a predator – and the subject becomes an object. Vincent goes inside a life and creates a new life.”

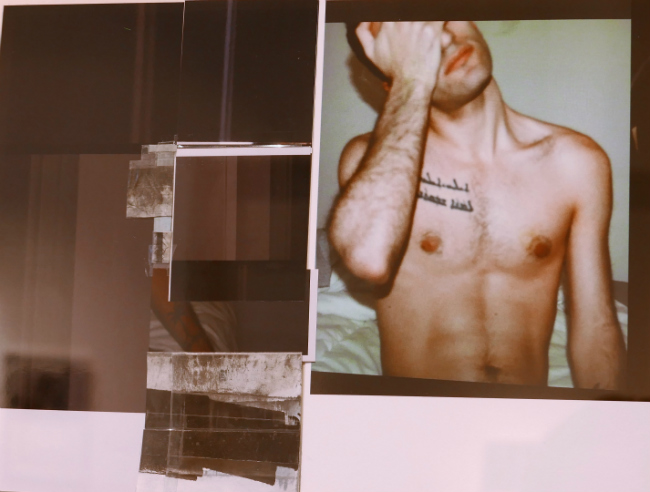

Vincent Gagliostro, 6 4 8 24 ref has Godard film (detail), 2018-2018, ©Vincent Gagliostro / photo by Diane Stamm

Among the most fascinating images in the exhibition are photographs of a young actor who has a tattoo in Arabic script on his chest that translates to, “My God, My God, why did you leave me?” If you have been following the groundbreaking shows of contemporary Arab art mounted by the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, you will know how this dovetails with the ongoing discussions in contemporary Muslim art and culture.

If the art in the Galerie NeC exhibition is, indeed, the storyboard for a new film – and Nilsson says that each work in the exhibition signifies its place in a sequence, as in film – then we are witnessing the ideas germinating in the mind of the creator. Gagliostro seems driven to create, as he has done throughout his life – driven to meld his ideas and experiences into art that tells a story. Where the narrative arc of his art and life takes him next remains to be seen.

Galerie NeC nilsson et chiglien

“Audition / 6:40 AM,” through February 24th

117 rue Vieille du Temple, Paris 3rd

Tel: +33 (0)1 42 77 88 83

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/galerienec.chiglien

Open: Tues – Sat; 11am to 7:30pm

Metro: Line 1, Saint Paul; Bus: 96

Author’s Note

There is one more AIDS-related film worthy of mention – “120 BPM (Beats per Minute)” (“120 Battements par minute”) – directed by Robin Campillo, released in 2017, and winner of the Cannes Grand Prix, where it received a prolonged standing ovation. Set in 1989, and in French, it is about the Paris branch of ACT UP and their sometimes disruptive, radical efforts to get the government and pharmaceutical companies to end their perceived foot-dragging and fight the raging AIDS epidemic.

One of its co-stars, 31-year-old Argentine-born, multilingual actor Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, is truly impressive. I met him before seeing the movie and was taken with the quiet force of his personality and his intellectual incisiveness, but I wish I had seen the movie first, so I would have known just how talented this modest man was that I was talking with. His performance as a young activist dying of AIDS is powerfully raw and courageously honest – a tour de force. While sometimes distressing to watch, the movie is an important cinematic addition to an important era of history, as is After Louie, discussed above.

Lead photo credit : "After Louie" directed by Vincent Gagliostro