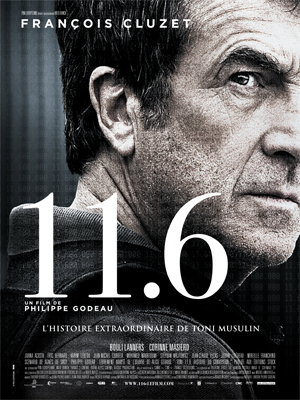

“11/6” – What Makes Toni Run?

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

A few years ago an armoured-car driver named Toni Musulin perpetrated a huge inside job that became France’s equivalent of the British Great Train Robbery and the US Brink’s Job. Those two thefts became movies, and now it’s the Musulin caper’s turn. But as portrayed in 11/6, it’s not much fun at all. It’s strange given that Musulin became something of a folk hero, but there was something strange about the real Toni Musulin and his caper. The loot was recovered very quickly, as if he’d stashed it in a half-hearted way, and wound up meekly giving himself up.

A few years ago an armoured-car driver named Toni Musulin perpetrated a huge inside job that became France’s equivalent of the British Great Train Robbery and the US Brink’s Job. Those two thefts became movies, and now it’s the Musulin caper’s turn. But as portrayed in 11/6, it’s not much fun at all. It’s strange given that Musulin became something of a folk hero, but there was something strange about the real Toni Musulin and his caper. The loot was recovered very quickly, as if he’d stashed it in a half-hearted way, and wound up meekly giving himself up.

11/6 (only the second film directed by Philippe Godeau, who’s mostly a producer) is a fascinating character study, well acted by François Cluzet. It is mostly a study in contained rage. Cluzet specializes in self-contained characters, putting on an impassive mask (with the exception of the occasional slashing smile). At first Toni Musulin seems to be a successful member of his proletarian world. He’s competent at his job, physically tough in a male-dominated milieu, has a sort of grudging popularity among his co-workers. Oh yes, he also has a Ferrari. It’s not clear how he paid for the car, which he buys for a six-figure sum at auction. He seems to have saved his money honestly, though not morally (his partner, who runs a restaurant, accuses him of never making any financial contribution to their life together). On one hand Musulin loves the car, the sensation of driving it, and the social cachet it gives him. But he has a miserly relationship to it—not tolerating others getting close to it, sounding half-serious when he suggests his partner should share gas expenses. Most of all, he seethes when people question why a working-class hero like him drives a Ferrari.

It’s possible that Musulin simply has a crippled personality, but this is depicted in an opaque way. The connections to his life either remain buried, or when the director and actor try to bring them out they don’t seem convincing. What’s worse he doesn’t have any redeeming qualities to compensate with—we wonder why his partner and friends put up with him at all.

The director films Toni Musulin’s world in a gripping, stark way that expresses the harsh working-class lives of the armored-car drivers. He portrays the brutal exploitation and unfair conditions powerfully. But when he adds agit-prop lines about globalization and high finance he actually dissipates that power. He also tries to make Musulin a tragic figure with a romantic longing for nature and solitude, who seeks a sort of rebirth (the title refers to the date one day after the planned heist), but this feels tacked-on and inauthentic. In the end Toni Musulin comes off as a nasty piece of work produced by a nasty environment.

The director films Toni Musulin’s world in a gripping, stark way that expresses the harsh working-class lives of the armored-car drivers. He portrays the brutal exploitation and unfair conditions powerfully. But when he adds agit-prop lines about globalization and high finance he actually dissipates that power. He also tries to make Musulin a tragic figure with a romantic longing for nature and solitude, who seeks a sort of rebirth (the title refers to the date one day after the planned heist), but this feels tacked-on and inauthentic. In the end Toni Musulin comes off as a nasty piece of work produced by a nasty environment.

The supporting characters have much more human depth than the protagonist. Corinne Masiero, playing Toni Musulin’s partner Marion, was a strong supporting presence as Matthias Schoenaerts’ sister in Rust and Bone. Here she plays the same kind of hard-bitten working-class survivor. Marion puts up with Musulin’s selfishness over the years out of love, but she’s no push-over and eventually reaches her limit. Bouli Lanners, who plays Arnaud, Musulin’s main co-worker, gives a wonderfully eccentric performance. Arnaud loves mice and dogs (and we think could go for Marion), but is most especially a true-blue friend despite bad treatment from Musulin. Like Marion he’s a tough survivor, but with a captivating childlike innocence.

What’s odd about the film is that for all of Godeau’s social realism, he never actually shows the drivers at work, making pick-ups and deliveries. The job of the armored-car driver in the Paris area is very particular. They pick up large amounts of cash from the plethora of ATM machines, banks and other establishments. They are among the few in the private sector in France licensed to carry heavy firearms—and from time to time they are victims of dangerous criminals even more heavily armed (attacks have occurred with rocket-launchers). In other words, one of your more high-stress professions—which might explain Musulin’s high-strung nature. But this is never adequately shown. On the softer side, we don’t get much insight into his relationship with Marion, either.

What’s odd about the film is that for all of Godeau’s social realism, he never actually shows the drivers at work, making pick-ups and deliveries. The job of the armored-car driver in the Paris area is very particular. They pick up large amounts of cash from the plethora of ATM machines, banks and other establishments. They are among the few in the private sector in France licensed to carry heavy firearms—and from time to time they are victims of dangerous criminals even more heavily armed (attacks have occurred with rocket-launchers). In other words, one of your more high-stress professions—which might explain Musulin’s high-strung nature. But this is never adequately shown. On the softer side, we don’t get much insight into his relationship with Marion, either.

The climactic section, when Musulin plans and carries out the theft, is riveting. Cluzet seems as maniacally driven as Robert de Niro’s Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. But what does he really want? All his efforts don’t add up to a desire for real bad-guy success or escape. The ensuing anti-climax is even more astonishing than the climax: it’s an 11,600,000 Euro fizzle.

Production: Pan-Européene

Distribution: Wild Bunch Distribution

More in 11/6, film review, french cinema, French film