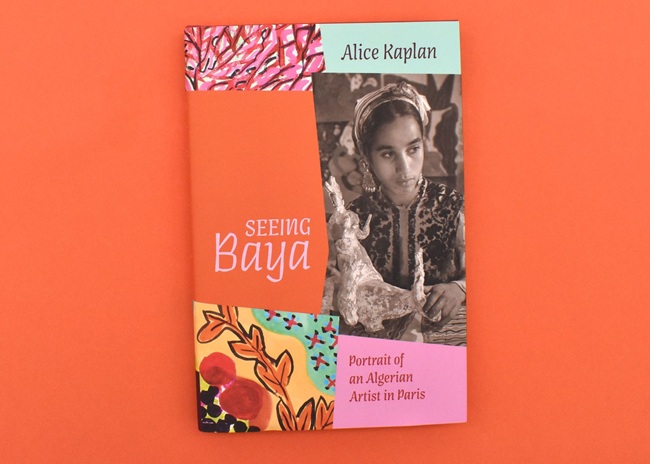

Books: Seeing Baya, Portrait of an Algerian Artist in Paris

In November 1947, an art gallery in Paris drew a distinguished group of leading cultural figures to an exhibition featuring the work of a 15-year-old Algerian girl. The opening was attended by, among others, François Mauriac, Albert Camus, and André Breton; Matisse and Braque were also there, and so was the set designer Christian Bédard.

Who was this girl who came from a precarious and impoverished childhood in rural Algeria to center stage in the postwar art world of Paris? How did she get there, and where did she go from there?

This is the story Alice Kaplan tells in Seeing Baya: Portrait of an Algerian Artist in Paris.

The book, published by the University of Chicago in a lavishly illustrated edition, tells the story of a young girl plucked from a life of rural hardship in the Kabylia region of Algeria, and unofficially adopted by a Frenchwoman, who brought her to Algiers. There the Frenchwoman encouraged the girl’s talent, supported her artistic development, and through her connections introduced her into the Parisian art world.

courtesy of The University of Chicago Press

But after her unlikely and dramatic success in Paris in 1947, Baya disappeared from the scene. Today she is largely forgotten in France, Kaplan tells us, though in post-independence Algeria, she slowly reemerged as “the country’s national painter,” and today is known in Algeria by “everyone…the way you know a myth.”

“The disappearance of women like Baya from the artistic and literary record is a global historical phenomenon,” Kaplan writes. “There are certainly a thousand stories like this one, yet Baya’s reached out to me the first time I saw her art.”

It is a fascinating story. Kaplan — a diligent researcher with an exceptional gift for storytelling — does not shirk from the challenging task of untangling the myriad and complicated threads of the story. The book covers the whole arc of Baya’s life, from her early years as a poor and mistreated orphan to her life as a comfortably situated wife and the mother of six children, who eventually returned to her painting and ultimately became known as one of Algeria’s most beloved artists.

Kaplan’s work is not only conducted in dusty archives and libraries, though she has done plenty of rigorous research there. But she also takes bold explorations into the contemporary world, knocking on doors with no guarantee they’ll be opened to her, determined to find whatever first (or second or third-hand) accounts of the events she is exploring she can find. In the process she takes us along with her on a journey that includes visits with Baya’s children and others who knew her in Paris, in Algiers, and in the south of France.

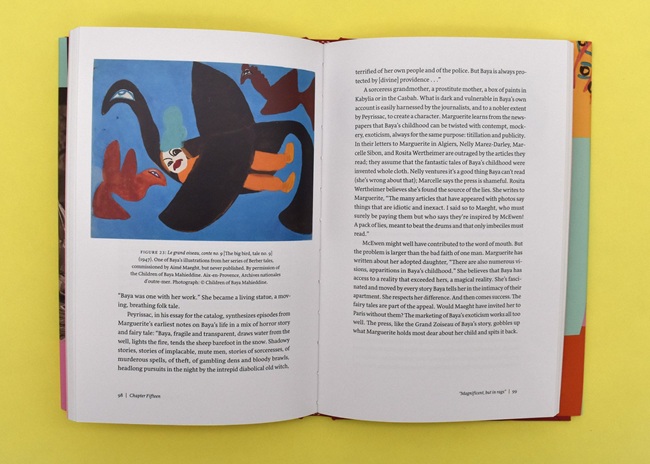

It’s a challenging task to say the least. Kaplan shares with her readers her difficulty in teasing out the real story, as free from her own personal interpretation as it is possible to achieve. Her attempt to untangle truth from untruth and one person’s truth from another’s is for me one of the most compelling aspects of the book. She writes:

I’ve transcribed in my notebook words of wisdom from Philippe Lançon: In fiction our readers believe what we tell them, because it’s all they have. In nonfiction we owe those readers an account of what really happened and what people really thought. But no matter how much information we gather, what really happened will always remain just beyond reach. And so I keep checking and double-checking, eliminating a mistake here, an inaccuracy there, leaving room to imagine what I can’t know, Because information, however invigorating, is never enough. I hold the details in my hands like so much sand.

Algiers in 1921. Public domain

Her deep knowledge of France during and after WWII lends particular richness to the story Kaplan tells in Seeing Baya. Since her expertise is not only in French language and literature, but also in the history of postwar France, for me one of the most interesting sentences in the book comes early on: “Thanks to [Baya’s] story, I’ll never see postwar France in the same light again.” For the period of time covered in the book is also the period of time in which Algeria was seeking to gain its independence from France, a bloody struggle that was ultimately successful. And that struggle is ever-present in the background of this story.

courtesy of The University of Chicago Press

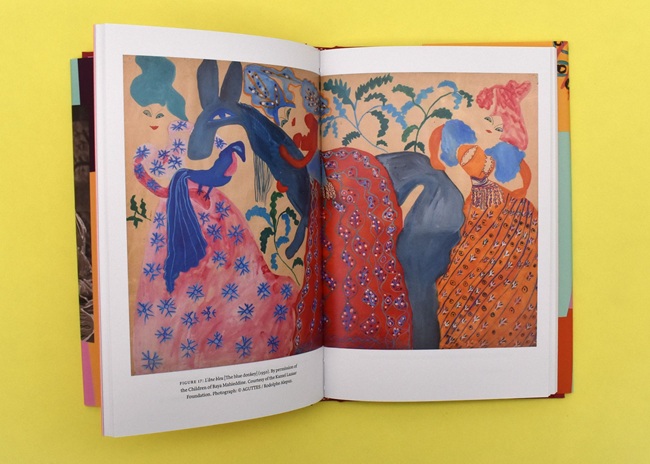

Beyond the story of Kaplan’s challenge in sorting out Baya’s biography, there is the story Baya herself left in her paintings and sculptures, many of which are reproduced in this beautiful book, in wonderfully vivid high-quality color plates. Kaplan concludes:

“Baya’s life, like her work, has lent itself to conflicting interpretations: For some she was a prisoner of the colonial gaze, then a wife and mother confined by Islamic patriarchy, a painter who is too pleasantly decorative or whose figures are too frightening. For others she was a luminous feminist who had emancipated herself from her cruel origins and eschewed French exile for family life and faith, and a pioneering artist who renewed a sluggish European modernism with popular and traditional Algerian forms. But her art, with its daring colors and its playful mastery of styles and motifs from Kabylia to Paris, has always spoken its own language.”

Seeing Baya is a fascinating story, and it is surpassingly well told in this book.

Purchase a copy for yourself at your favorite independent bookstore, like the Red Wheelbarrow or Shakespeare & Company in Paris, or via Bookshop.org.

Lead photo credit : courtesy of The University of Chicago Press