On Poetry and Paris: An Interview with Author Cecilia Woloch

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

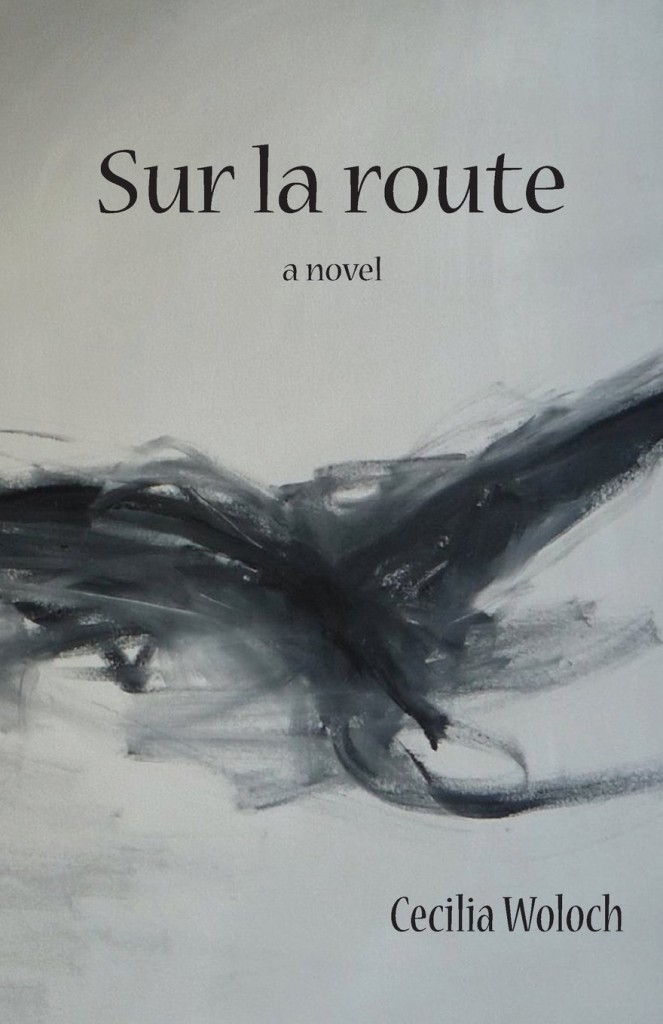

Cecilia Woloch, the award-winning author of six collections of poetry and founding director of The Paris Poetry Workshop, teaches throughout the U.S. and around the world, and spends parts of each year in Paris. She is currently in Paris to promote her latest work, Sur la Route, a poetic novella set in Paris, which has just been published by Quale Press. Woloch grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and rural Kentucky, one of seven children of a homemaker and an airplane mechanic. In recent years she has divided her time between Los Angeles, Kentucky, Paris, and the Carpathian Mountains in Poland. She recently took the time to answer BP writer Janet Hulstrand’s questions about her work, and her thoughts about Paris.

JH: When did you first come to Paris, and what drew you here? Were you looking for something specific? If so, did you find it?

CW: I first came to Paris as a college student. I guess I was nineteen years old; it was probably 1976. I was in London with two girlfriends who were also theatre majors. We were supposed to be doing a “short-term” course, between Thanksgiving and Christmas, with our university; but we were the only three students who enrolled so our professor wasn’t able to come along. So it was just the three of us, running around London seeing plays and writing about them. Both of these young women had been in Europe before – they were from much more well-to-do families — so it wasn’t as big a deal to them as it was to me. I wanted to see everything I could see, experience everything I could experience. So when an opportunity came to go with one of my friends to Paris, to visit friends of her parents, I jumped at the chance – though lord knows I couldn’t really afford it.

We flew from London to Paris, each of us wearing jeans and boots and a turtleneck, each of us with a backpack with her toothbrush and notebook and maybe a change of underwear. I think we only planned to stay a day or two, and ended up staying much longer. We ended up switching turtlenecks, just so each of us could vary her wardrobe a little. And it turned out that the friends of my friends’ parents were George and Betsey Bates, who were both on the staff of the International Herald Tribune, which had offices on the Champs-Elysees in those days. Really, I was completely unprepared for the glamour of it all. George and Betsey decided to take us to the Lido and Betsey outfitted my friend and me from her own closet. What a time that was! George and Betsey had very busy lives, of course, so they also left us to our own devices a lot. They gave us a Plan de Paris and told us to have fun. By our third day, I must have looked supremely confident making my way around the Metro, because French people started asking me for directions. I got to try out my college French, because little English was spoken in Paris then. I also remember a very sexy moment in the typesetting room of the Herald Tribune – an underground room full of noisy machines, which I remember as smoke-filled and steamy from the rain. Or maybe I was the steamy one? I was standing on a metal staircase, on my way back upstairs, when a handsome young typesetter walked over, took each of my boots by the heel, first one then the other, and trimmed the raggedy hems of my bell-bottom jeans with his pocketknife. I don’t know what I’d gone to Paris looking for, but I was completely hooked by the time I left.

JH: How much time do you spend in Paris now? And what are some of your favorite neighborhoods and/or spots here? What is your favorite thing to do in Paris?

CW: I’m usually here for a few months each year, a month or two in the summer and a month or two around the winter holidays, but that changes from year to year. For a few years, I was teaching a course in Paris for undergraduates from USC that ran for a month; now I’m running independent week-long workshops for writers, and I try to organize one of those in the summer and one in the winter. These days when I’m in Paris, I mostly like to find a good spot to write for a couple of hours a day, and then I walk around a lot — I can’t ever get enough of walking in Paris — and I spend most evenings with friends. I’m lucky to have the circle of friends I have in Paris, friends in the expat and writing communities, and also my two French families. I go with friends to museums and galleries, and restaurants and cafes, of course, and I love going to the cinema in Paris, and going out to hear live music. I just try to live the kind of life I’d be living if I lived in Paris year-round.

JH: How did you become a poet, and when did you first start writing poetry?

CW: I like to answer this question by quoting the poet William Stafford. When someone asked him when he started writing poetry, he answered, “When did everybody else stop?”

Honestly, it’s hard for me to remember a time when I didn’t write poetry. My mother read to us a lot when we were small – I have two brothers and four sisters – and she sang almost constantly. So we were always making up little songs and rhymes and stories. I started scribbling things in secret probably as soon as I was physically able to write, as I think many children do, and I started scribbling in notebooks when I was a teenager, as do so many teenagers. And somehow, I never stopped, probably because I got a lot of encouragement. I had a high school teacher, Joann Bealmear, who was a poet. She introduced me to a lot of contemporary poetry, and encouraged me to write and to take myself seriously as a writer. She was responsible for getting my first poem published in the journal of the Kentucky Society of Teachers of English. Her faith in me helped me to see myself as a poet. She also got me started on the lifelong habit of keeping a journal.

My parents were also always very encouraging. They were both from poor families and grew up in the inner city; neither of them had been able to finish high school, but they were readers and they encouraged us to read. And reading is what led me to writing; for me, the two activities are almost the same, one leads kind of seamlessly to the other. It has to do with a love of language.

I also think I was lucky to grow up when I did, during a time when the liberal arts and creative self-expression were seen as important and worthwhile pursuits, even for a working-class kid. I studied literature and theatre in college. And then I moved to Los Angeles and became part of a poetry community that was really supportive and exciting. I took workshops with more established poets and, in turn, led poetry workshops for kids in the public schools. So I was actually able to support myself by working as a poet in my community. All of these things fed into one another. Teaching poetry to kids meant that I had to keep teaching myself about poetry — because kids ask such tough questions — and it also kept me close to the magic of poetry, and in touch with my own imagination. The more established poets I studied with helped me learn to revise my poems and work toward getting published. Though, ultimately, the only way anyone becomes a writer is by writing.

JH: You’ve taught poetry workshops for professional writers, educators, senior citizens, prison inmates, and residents at a shelter for homeless women and children, among others. Why is poetry important, especially for people in crisis? Why is it important for all of us?

CW: I think that poetry, of all forms of writing, is most closely aligned with the pure magic of words, of language. As human beings, we all have access to that magic, and to the imagination. When people tap into that magic — whether by reading or writing poetry —it’s empowering in a way that almost nothing else is. It can make us feel more alive, and more human, and more forgiving of ourselves. The best poems have an emotional intensity that goes right to the heart. Some of the best poems I’ve ever read were written by children and by people in desperate kinds of situations. You don’t need a big canvas to make a poem, you don’t even necessarily need a lot of time. You don’t need an advanced degree or a lot of expensive tools or a huge vocabulary. You only need the words that are unique to you, and your unique way of seeing the world, and some inspiration and encouragement. As a teacher, I feel that providing encouragement — in the sense of giving heart — is one of the most important things I do. And I believe that having access to our creative power — which is a transformative power — is essential for every one of us. Poetry can connect people heart-to-heart and soul-to-soul, and poetry changes lives — I’ve seen it happen over and over again.

JH: I’ve just finished reading your novella, Sur la Route, which is wonderfully poetic, a kind of complex-yet-elegantly-simple coming-of-middle-age love story set in Paris. And, although this is not the most important question to ask, I can’t resist asking: how autobiographical is it?

CW: Oh, I love your description, and think you’ve gotten it just right – thank you! Yes, it is a coming-of-middle-age love story and, frankly, it’s pretty autobiographical. I suppose that, having first been a poet, mining my own life experiences for subject matter seems natural to me – really it seems inevitable. I also think the novelist and writing teacher John Gardner was right when he sad, “Everything we write is autobiographical, even when we’re writing fiction; and everything we write is fiction, even when we’re writing autobiography.” The line is really blurred.

JH: One of the interesting things I noticed in Sur la Route is the extent to which the main character relies upon a rather tenuous and unpredictable network of human connections–friends of friends, and sometimes friends of friends of friends–to help her move from stage to stage in her journey. Many, if not most, people would be reluctant to strike out into the unknown the way she does, trusting to a great extent in “the kindness of strangers.” And yet it is her willingness to do so that brings her significant rewards of adventure, friendship, even love. Do you want to comment on this aspect of the novel, and what it may imply about your own beliefs about the delicate balance between maintaining personal safety and allowing for serendipity to play a positive role in human lives?

CW: Here again, I love your insight into the protagonist and the plot – if we can call it a plot. Yes, it’s that very willingness to take the risks she takes and to trust in the kindness of strangers that brings her such rich rewards. And the fact that the novel is set in the mid-1990s, and that the first draft was written twenty years ago, is pretty significant, I think. Could a story like this even happen today, with the ubiquitousness of cell phones and all the apps for tracking people and keeping in touch, and GPS, and Google and Facebook? Really, I doubt it, and I think something pretty precious has been lost – not only all the possibilities of serendipity, but the challenges of testing and discovering one’s resources and, yes, the magic of random – or fated – human connection. When I gave the first reading from the novel in Los Angeles a few months ago, I was waxing nostalgic about those days when you had to figure out how to use a foreign pay phone, when you had to ask strangers for directions, when you had to throw yourself on the mercy of people some inner voice told you that you could trust, and I said, “I don’t even know how people manage to fall in love anymore!” But of course I do know; they use the Internet for that, too, which makes for a different kind of randomness, I guess. Randomness by algorithm, maybe. Well, to me it’s a kind of loss. Because I think that when we take these kinds of risks on a regular basis, the risk of human interaction, we hone our instincts at the same time, and we refine that mechanism by which we know who we can trust, and when we need to protect ourselves. I also think that, in my own life – being nakedly autobiographical here – people have responded to my willingness to trust them, and to open myself, by opening their lives to me, and their homes, with enormous generosity. And of course I’ve moved in certain circles – artists, writers, musicians, travelers —and that’s made a difference, too.

JH: Your poem Tsigane has recently been translated into French, and parts of it have been interpreted in multi-media performances in various places around the U.S. and in Europe. Can you tell us a little bit about this work? What is it about? What moved you to write it? Are there more performances planned?

CW: The director of the first multi-media performance of Tsigan: The Gypsy Poem—which was part of the Visions and Voices program at the University of Southern California in 2013—described it as a “live documentary.” I like that description a lot, because I’ve always thought of Tsigan as having cinematic qualities – or maybe it has cinematic aspirations? This is a poem that wants to be a movie, I think!

But it began as a way of addressing an obsession I’d had, since I was a child, with finding out whether there was any truth to the rumor in my family —always invoked when one of us did something “wild”—that we had “Gypsy blood.” The poem is the result of a search for my tribe, for a grandmother who disappeared before I was born, and it weaves the chronicle of my personal search into a chronology of the history of the Roma people — also called Gypsy, Tzigane, Gitane, Romani, etc. When I started writing the poem, I didn’t know about the Porrajmos — the Gypsy Holocaust during WWII – and, being American, I hadn’t realized how ostracized and despised Gypsies were, and still are, in Europe. I originally thought I would write a single poem in several sections; but the poem took on a life of its own and ended up being book-length, a long poem broken into sections, with historical information interspersed throughout, and with a narrative arc that traces a series of journeys I took, in the 1980’s and 1990’s, that led me eventually to the Carpathian village where that mysterious grandmother of mine had been born.

When I was writing Tsigan, I honestly thought it wouldn’t be of interest to anyone but myself and my family. It was published in a small edition by Cahuenga Press, a small cooperative press in Los Angeles, in 2002. But it’s turned out that this little book has a life of its own, and wings. It’s shown up in places I never expected it to go, all over the world. The book has been included in exhibitions in Germany and Poland. The text has been used in multi-media performances and film. It was translated and published in French in 2014 and, this past January, sections of the text were translated into Polish for a performance at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, as part of the museum’s commemoration of International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Most importantly, it was also my mother’s favorite of the books I’d published before she died.

At the time I was writing Tsigan, it was really difficult to do research on anything having to do with the Roma; Roma history has been transmitted orally for as long as anyone can tell, so there just wasn’t much documented information available. Now there’s much more, and I’ve met so many people all over the world as a result of the book being out there that I’m thinking I’d like to add some material and publish an expanded/updated edition, especially since the original edition has been out of print for a number of years. We’ll see.

As to performances, each of the performances thus far has been very different. In Los Angeles, the presentation incorporated filmed testimony from the Shoah Foundation archives of Gypsy survivors of Nazi concentration camps, a Flamenco dancer and musicians, and a French Gypsy cante jondo singer. The French performances have been less extravagant, but have also included live music, and a kind of braided reading of the text in English and in French. (The French translation was done by Jennifer Bocquentin, and it’s exquisite, I think.) The performance at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw was also bi-lingual, and included accordion music specially composed for the text, projections of archival footage from Auschwitz, and photographs of Gypsies by the Danish art photographer Joakim Eskildsen. I love seeing the work realized in so many different iterations.

There’s a performance scheduled in Annecy on October 31 of this year, and there’s likely to be a repeat performance at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in 2016. The Polish translator, Jan Pieklo, and I are also working on the possibility of a presentation in the museum at Auschwitz; and the director of the French performances, Anastassia Politi, is looking for a home for a more fully-staged Tzigane with a French theatre. I’m open to every possibility, and would love to hear from anyone who has an idea about a potential venue.

JH: What do you love most about being in Paris? What do you get from spending time here?

CW: I love being able to walk everywhere or get wherever I need to go by public transportation. I love that there’s so much beauty at eye-level, always, which makes walking such a pleasure. I love the human scale of things and how all my senses are engaged. My French gets a little bit better every time I’m here, especially if I spend a lot of time with French friends. Mostly what I love is the sense of myself that I have when I’m in Paris: the sense of being fully present in my own life and comfortable in my own body. I’ve always thought that Paris is a wonderful city for women; you can be independent here, and autonomous, and that autonomy and independence will be respected. You can also feel confident and attractive, even at 58. When you walk around Paris, no matter your age or size or whatever your particular appearance, you’re part of the beauty of Paris, too.

JH: While your main home base is Los Angeles, you spend significant amounts of time in France, in Poland, and in rural Kentucky. What are the pros and cons of such a lifestyle? Is there one place you feel most at home? Or do each of these places feel like home to you?

CW: A lot of places feel like home to me, and that’s getting to be a problem. Though I love being in motion, and I don’t seem to have a big need for stability, I’d really like to have a base in the U.S. that feels like home, and a base in Europe. I don’t think I could live in any one place all the time, but maybe that will change.

JH: What’s next? What are you working on now?

CW: I’m working on several things at the same time, always, even when I think I’m only doing one thing. I have a new full-length poetry manuscript that’s nearing completion, and a collection of essays that’s getting close. But the main focus of my writing for the past ten years has been a long work in narrative and lyrical prose, a kind of travel memoir and family history and geopolitical murder mystery, all rolled into one. It centers on that paternal grandmother who was also the inspiration for Tsigan, and who “disappeared” before I was born. It seems she was murdered, and the murder was covered up, and it all had something to do with the political underground she was a part of, which seems to have extended from the U.S. back to the village where she was born in the Carpathian Mountains of southeastern Poland. I wasn’t quite prepared for all the research I’ve had to do to get the material for this book, and all the travel, but it’s been quite an adventure. And this is the book I feel I was born to write —if there’s any such thing as being born to write anything — and the reason I became a writer, in the first place. So that I could tell this story.

Lead photo credit : Eiffel Tower/ Cecilia Woloch's writing workshop

REPLY